Diane Kirkpatrick is a Professor Emerita in the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Eduardo Paolozzi, focused on the major themes of the artist. Here she sits down with us to discuss her relationship with Paolozzi, as well as the ideas behind “The Grandfather of Pop Art.”

Lillian Pearce (LP): How were you introduced to Paolozzi? How did this relationship blossom and end up with the two of you collaborating? How did your relationship connect to your career as an artist and professor?

Diane Kirkpatrick (DK): I was lucky. I went to Vassar College as an undergrad, and I had always been interested in art and making art. I had a professor who was a painter and encouraged my painting and interest in sculpture. So, I went to Cranbrook and got a Master of Fine Arts. I realized in the 50s that I didn’t really want to be an artist; I wanted to be someone who could write about art and teach about art, so I needed a Doctorate of some sort.

One of the people I had been at art school with at Cranbrook was a sculptor, who had spent the previous year at the Courtauld Institute in London, and she said that I could apply to be an external research student. Although I couldn’t take the kinds of intensive classwork where students work with a single professor, I could attend any lecture I wanted and could get acquainted with the professors.

I knew then that I needed to have a Ph.D. So, I went to the Courtauld but arrived early in September though I couldn’t move into my residence hall until the end of September. I was invited by a former classmate of mine from Vassar to stay with her family near London. So I had quite some time on my hands. I began looking at lots of different sculptures and spending time at exhibitions in Battersea Park.

After I had started at the Courtauld, I was going to galleries, and I walked into one, and there was this sculpture that was the craziest and most interesting thing I had ever seen. I found out that it was the work of Paolozzi, and I researched him in the British Fine Arts Department, and they arranged for me to have an interview with him in his studio.

So, I went to his studio and was absolutely fascinated by what I saw. And he was interested because here was an American who was interested in his work. So, we were introduced, and when I went home at the end of my year, he said, “You’re coming back to study, right? Contact me when you get back because I would like your feedback.”

So, he invited me to come back and work with him. When I returned, that’s the time I had this heady thing of being the receptionist for him as people would come up the stairs to his studio. He had this young German sculptor who would help him with all the tech techniques, and we would go out for a meal quite often together, but Eduardo never paid. So Arturo and I had to dig up. We had to be sure that we had some pounds and pence with us. Eduardo was never really ridiculous about it. But it was just funny. It got to be terribly funny.

LP: You said he was interested because you were an American interested in his work. Is it true that Paolozzi was fascinated with American culture?

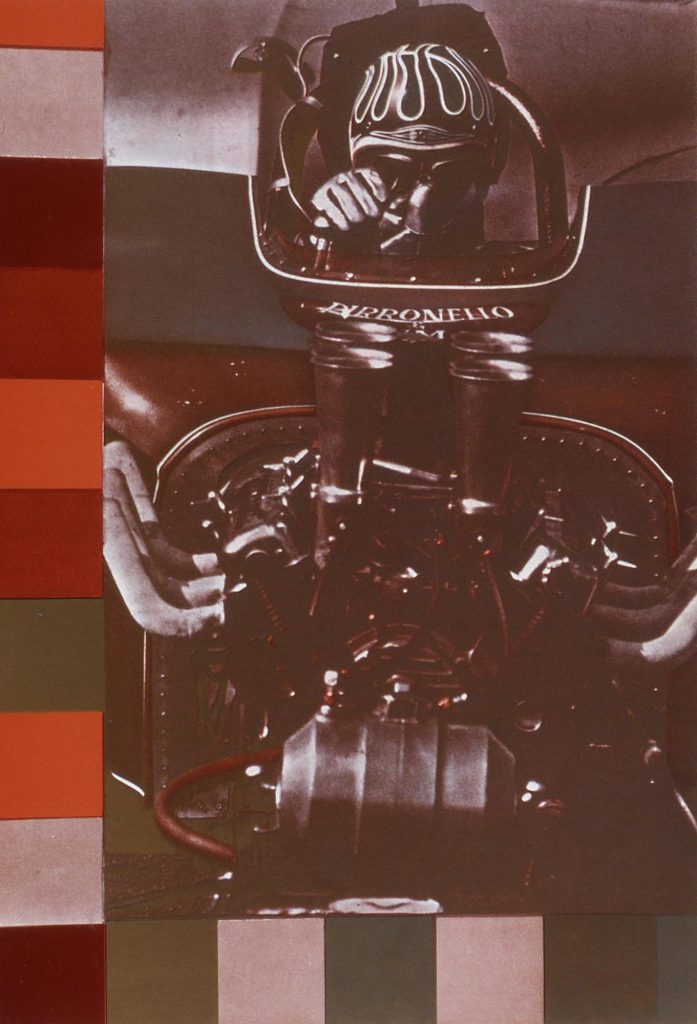

DK: He loved American advertising; he wasn’t the only one in England fascinated with American culture. He and Richard Hamilton, a good friend of Eduardo’s, loved American advertising. They explored the metaphysics and the interesting ideas they found in American advertising, which seemed to them to be a very rich country.

LP: What else do you remember of Paolozzi? Can you speak to Paolozzi as a person or as an artist?

DK: He had a very, very interesting life. There’s no doubt about it. He was a public artist, a very democratic one. He never, almost never, expressed distaste with another person. He was somebody who could see and appreciate the shortcomings as well as the long coming of people.

He was very interested in people and the way they responded to things. And so he would notice something. And he would say, “What do you think about that?” and begin involving you in conversation.

There were a lot of openings. And he usually would go to the opening. There’d always be people around him because he was very interesting, and somewhat ribald on occasion, conversationalist. And he would get very enthusiastic about toys he had; they were all over his studio.

It’s true that he wanted to be inside and outside the art world at the same time, but he was on public performance whenever he was out. And that performance, he was a black belt in judo, he kept his body very trim.

LP: And since your time with Paolozzi, have you felt like his work has been broadly overlooked? In an article I read from the British Art Journal published in 2015, Elly Thomas wrote that “while Paolozzi had certainly not been forgotten, he did seem to have been ‘left behind.’”

DK: That’s not true. He’s had many, many exhibitions. I will locate an essay that I was commissioned to write by an art gallery that carries his work for a special exhibition of sculpture, which indicates how not left behind he has been everywhere else. His public sculpture is all over London.

LP: Thank you. I had been pondering that question myself because my other research has proved otherwise. People call him the “Grandfather of Pop Art.”

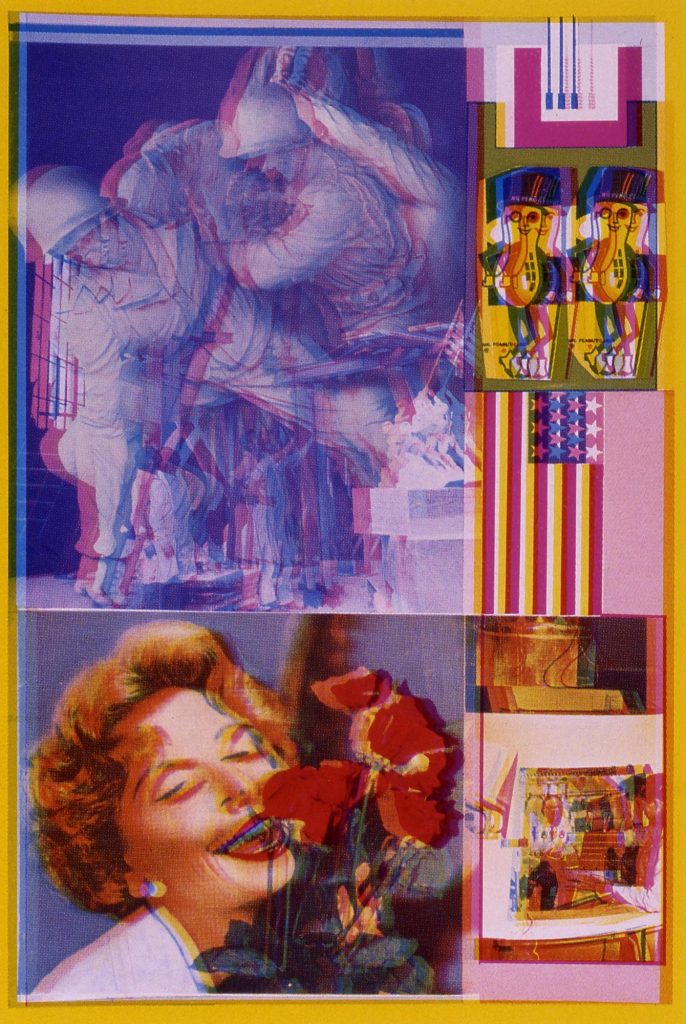

DK: All the members of The Independent Group were grandfathers of Pop Art. They all appreciated Pop Art because of the “aesthetics of plenty.” They saw it as such wonderful material to work with. Eduardo was famous. I think they used an overhead projector, and they would come and give talks, and they put down images that they wanted to talk about. Eduardo was famous for coming in with a large stack of things that he had gathered from publications, from placards, etc., and he would put it down as fast as he could. One after another. They said it was like a blitzkrieg of images. He would give people just enough time to focus on an image, and then he was putting down something else and putting it down hard with his hands and holding it, you know, so that they could see it.

He became someone that influenced a great many artists in Britain as well as outside of Britain. And he had a core group of people within England who worked with him, but he also was very young because he had been interned for a while, so he was behind. He was very young in the art world terms.

LP: That’s interesting. And what do you think, is there any significance for you that the Michigan Quarterly Review is using Paolozzi’s artwork for the cover? Do you think it is important for us to introduce our readers to artists and their work, especially those whose work is at the University of Michigan Museum of Art?

DK: Absolutely. Paolozzi was interested in symbolism; he was interested in language—visual language, machine language—patterns of all kinds. He paid me with art, which I was very happy for. But I realized it was not fair to the world to keep the large portfolio because that is him at his best in printmaking. I did give UMMA my large portfolio; I thought that I shouldn’t keep it, it’s too valuable.

Can you remind me of the work that you mentioned that’s going to be on the cover?

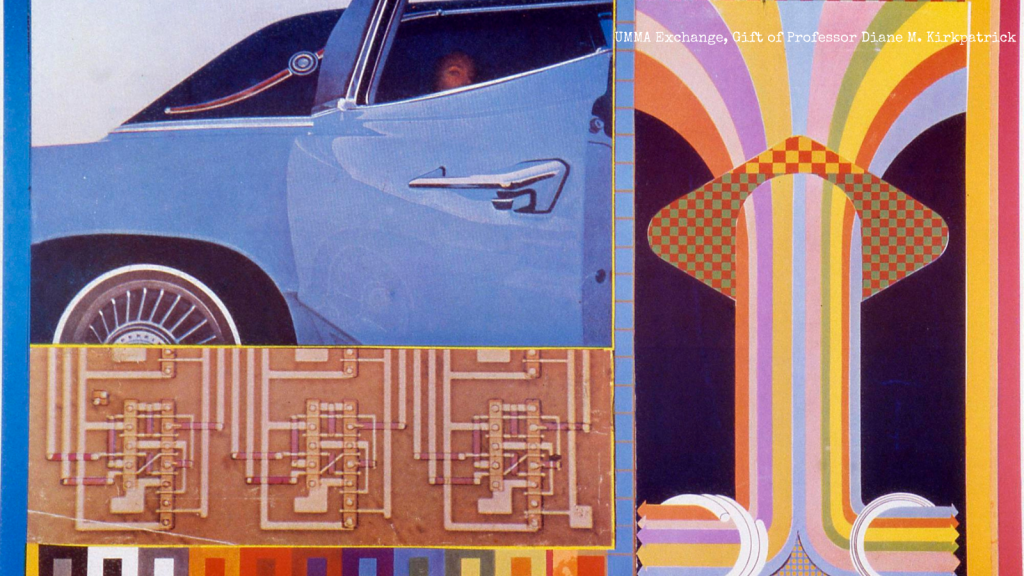

LP: “Spontaneous Discrimination Nonspontaneous Discrimination.”

DK: The titles don’t stick with me because they all are montages. But I’m glad that they’re using that; it was just interesting. It sounds like the kind of thing he would do because he loved the sound of words, and that’s an antithetical thing. You’ve got two things going on that are opposite at the same time, but I don’t have any image in my head for it. He made so many things.

In any case, they’re collages. Some are humors, some are sad. You can interpret them, do whatever you want.

LP: Did his collages, or work in general, evolve or change over time?

DK: His work in the 60s and 70s has a sense of robotics about it. Later in life, he began doing some things that went back to having more humanoid qualities. He also did things that were fun. I don’t remember the one you talked about. They are all similar in some ways. I will welcome seeing what it looks like.

Cover photo: UMMA Exchange, Gift of Professor Diane M. Kirkpatrick