Into the disordered evening my brother cut out only his face from every photograph in the hall, carefully slipping each frame back into position What good does it do?

Ghost Of by Diana Khoi Nguyen suspends itself between elegy and séance. These poems shove us into the stomach of grief as they re-embody the deceased—Nguyen’s own younger brother—whose absence is a tangible presence “dangerously close to living.” She intricately braids family, fantasy, and nature into a spellbinding witness to grief and the ghosts that carry it. Forms shapeshift from tidy to scattered, their language oscillating between lucid and slippery, as Nguyen shows the process of mourning for what it is: a hurtling, frenetic heartache and a desperate search for logic. The title, Ghost Of, insinuates an obligation to fill in the blank. Though this collection revolves around the brother, it implicates a whole world of ghosts—of refugees, childhood figments, past versions of ourselves—and pushes us to consider how our own bodies are constituted by accumulation of loss.

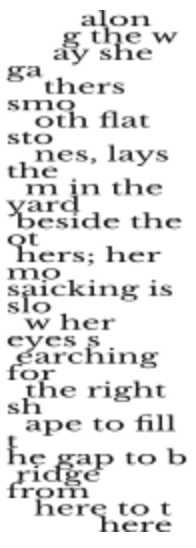

One of the most compelling elements of this book is the brother’s agency in this post-mortem absence. Family photographs, from which he cut his shape two years before his death, give Nguyen a communicative medium. As Nguyen sculpts her poems into, around, and in the echo of the photographs’ negative spaces, both the image and the text evoke the brother’s hand; his own act of excision seems removed from the poems only by time, which pales against the muscle of grief. As a whole, this collection eschews temporal and situational boundaries. The details omitted about the brother—how he died, how old he was, what strained his family dynamics—speak to the fact that this book is not so much about remembering the past but interacting with the brother as a tangible absence. While these poems hang on the tender wavelength between siblings, a profoundly personal tenor bound to mystify any outsider, they also entangle the reader in the similitudes of grief that inscribe the human experience.

Threaded throughout the collection are two series of visual poems guided by the family photographs. As “Triptych” and “Gyotaku” work in and around the negative spaces of the brother’s form, they play with the very body of his ghost. “Triptych” is an eponymous series in which the brother’s shape pulses throughout the following poems, both filling and avoiding his excised spirit. The repetitive form feels almost like an experimentation of different ways to see the brother, remember him, and re-body him. His absence carves into the following poems regardless of whether the poems relate explicitly to him—a testimony to grief’s ability to touch everything it encounters. Every poem, like every lived moment, contains his pervasive echo, as Nguyen tries to iterate “what may exist between appearance and disappearance, between sound and silence, as something / that is nearly nothing—.”

The next series, “Gyotaku,” refers to a traditional Japanese art form of printing fish, in which a fish body is painted and pressed onto paper. In this visual series, the photo and their afterimages become chaotic reckonings of the brother’s ghost as they take a life and authority of their own. The shape of his absence is re-arranged into snakes, dagger-like threats, sometimes multiplying to the point of incoherence. In one Gyotaku poem, the brother’s name, Oliver, is finally revealed as its repetition fills his silhouette. Within the shape, “Oliver” interchanges with “elver,” as Nguyen seems to confront that this fantastical childhood pseudonym is the same being as her brother who has died, aligning the presence of suffering with the joy of the past. The adjacent page fills with multiples of this name-body-shape as if Oliver’s body has been stamped over and over, trying to recall his being through the motion of Gyotaku. The resulting chaos becomes a statement on the frustrating inability to communicate the full suffering of loss, as the repetition begs the frantic question of How many—? How many times can the brother die? How many times can he be remembered? How many versions of the brother now live in Nguyen’s memory? In Nguyen’s reality?

Nguyen entangles human grief with ecological processes in the very first poem, which begins: “There is no ecologically safe way to mourn. / Some plants have nectaries / that keep secreting pollen even after the petals have gone.” Throughout this collection, the natural world curls to scape the setting for the elver’s surreal adventures, through which Nguyen parallels his childhood yearn for fantasy with his adult desire for death. The role of nature stretches into the philosophy of grief, as Nguyen herself scours both the physical and imaginative realms for a sense of logic in loss.

This attempted rationalization of loss unearths a question buried deep in the gut of this book: Is the human world a place where loss hurts, and the natural, animal world a place where loss makes sense? Nguyen twists this tension by carefully intertwining animal and human woes before finally coming to admit:

Nature makes mistakes: my siblings and I playing orphan in the wilds we built with plastic. […] In the unkennelled cold, a bird’s song splatters against moist leaves its lyric out of sync with melody.

Her musings acquiesce that “nature” includes both the external environment and our internal nature, each organic and vulnerable to human pollution. Therefore nature, which we often assume to be balanced, perfect, and fated, can be as wrong as human error. Regardless of this realization, Nguyen’s poems continually cave to the desire to rely on the natural world for logic and whatever consolation can be found in its sense. When she ends one such grapple with, “Once more I begin to move in the direction of the animals,” it is unclear if her tone is one of tenacity or resignation.

Throughout the book, nature also serves to mediate a tension of placelessness that springs from the family’s migration after the Vietnamese War. Nguyen connects this trauma of displacement to the trauma of her brother’s death, interrogating how ghosts are stitched into the fabric of a family, a country, and a history. At times, Nguyen allows us to see beyond the brother into the world of ghosts conceived by exile—just as ghosts exist between the world of the living and the dead, the placeless exist between spaces of belonging and may require the same effort of remembering. This tension enters through “The Exodus: Saigon to Los Angeles, 1975-2015,” which haunts the reader with the motion of remembering, painfully tasked with tracing how ghosts come into being. The poems culminate in her brother’s funeral and a direct address to him:

Maybe you’d forget why you were here, that you didn’t belong, that just because it was like life, didn’t mean it could be life that you could come back to life but not return to living. And if you bypassed a war, a war wouldn’t bypass you

By investigating the construction of family, Nguyen leaves us with more questions than answers, as her poems beg: How do we define ourselves each another? How do we divide ourselves from each other? Where is the barrier between? Is it possible to say?

Throughout this book, Nguyen’s poems spiral through skeins of logic that excavate the containers of absence. The role of place re-surfaces in “An Empty House is a Debt,” in which Nguyen interrogates vessels of emptiness, including the empty house of her body. She says, “I reach inside my empty house: as far as I’m allowed to go. / I reach outside my empty house: as far as I’m allowed to go,” an acknowledgment of strength emptiness can have. The poem tumbles loosely into a logic tied together by this thread: she is a house, the house is empty, and emptiness is Oliver; therefore, her body is Oliver’s house. As such, Nguyen takes advantage of the freedom of poetic intellect to build her own theories into the world of suffering.

This gives the brother agency in the construction of Nguyen’s very body. As this body is both a shelter for her brother’s absence and a vessel through which Nguyen processes her grief, it seems almost as these poems are a collaborative effort between brother and sister; by virtue of sharing a body, the brother becomes a literal “ghostwriter” of this collection. Though this logic unfolds slowly throughout the book, its foundation is established early on when Nguyen moves seamlessly from a recollection of a car ride with her brother, to his funeral wake, to the image of ants picking a body clean:

but this will sting, I said when I held my mother and put my brother’s hand back beside his body. The ants move closer closer and closer. The ants move into my camera and move on. The ants move into my head my mouth I taste the ants and I swallow the ants

Thus, the sister and the brother elide, causing us to ask Whose body?—a question that echoes deeper to become What is a body? as the boundary between the physical and the remembered wears thin through the endeavor of recollection. Throughout, this book reminds us that our departed loved ones exist as much as we do, as we become the bodies for their memory.

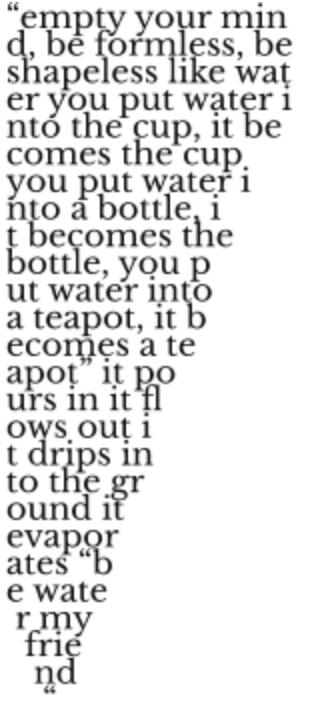

As absence has its weight, it also has warmth, as Nguyen aptly puts, “Tell me what we lost as collateral is also a gift.” Her final attempt to rationalize loss comes in the end, as she again turns to nature through metaphors of water. In “Coda” (pictured right), Nguyen guides us through an associative journey that follows: we are made of water, water takes whatever shape you pour it into, we pour water into the ground, and the water evaporates; therefore, we evaporate and, likewise, never really disappear. Her choice to speak through water conjures its essence of permeability—it can fill, soak, nourish, and be recycled through many forms and bodies, just as sorrow can leach through every shimmer of our lives.

There’s a certain grace with which Nguyen admits the futility of making sense of death yet accepts that it is not a choice; grief has no solution but exists as a state of being, a body to be continually carved into various shapes. Despite her strained relationship with her brother during his life, these poems exist not so much a reconciliation as a closeness—a new way to hold him, to reclaim what was lost in life, in death. This book is not a tool of healing, but as a testament to the asperous, mangled grief embedded within that process. The mourning song which began long before Oliver died, will continue long after his death, borne by the bodies tethered to his absence.