I tend to read—or at least have on my bedside table—multiple books at any time. Generally, they’ve got little to do with one another, aside from being books I’m reading/am interested in and simply pile up as I work my way through them. But occasionally, the juxtaposition of otherwise random titles leads to unplanned synchronicity. More simply, links—suggested, implied, inferred, what have you—between books appear.

Case in point: a few months ago, I decided it was time to re-read Lauren Levin’s The Braid (Krupskaya, 2016). Briefly, The Braid is an arresting meditation on motherhood and is written in Levin’s signature discursive, meandering, conversational style. The work is simultaneously prosy and highly “poetic,” insofar as it’s marked by abrupt line breaks and shifts and irregular punctuation that is super effective despite their irregularity. Here’s its title poem.

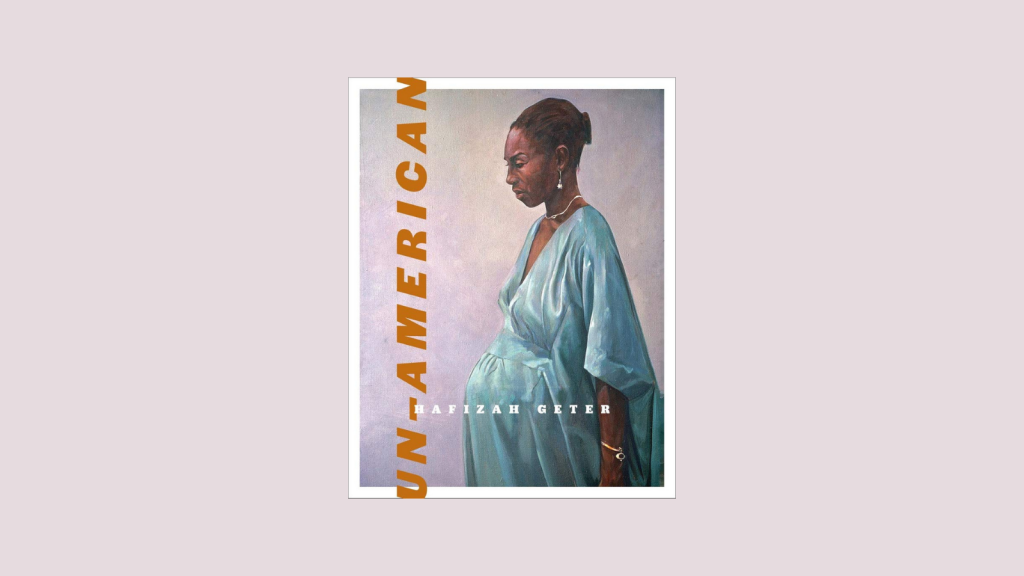

Hafizah Geter’s debut book, Un-American (Wesleyan, 2020), has also been on my bedside table. While significantly different from The Braid in several important ways, Un-American nonetheless complements it. Hence the referred-to synchronicity above. Where The Braid is about motherhood, Un-American is largely about being a daughter; a painting Geter’s father painted of her mother serves as the book’s cover image. The work in Un-American is also rather different formally and tonally from Levin’s; Geter’s lines are crisp, and her tone is removed and austere. But the poems in Un-American are hardly muted: just like those in The Braid, they crackle and simmer with heat and vitality.

Here’s a representative example, the closing lines of “The Break In”:

I close my eyes and see my father sulking like a pile of ashes, his hair jet black and kinky, his silence entering a thousand rooms. Then outside, trimming hedges as if home were a land just beyond the lawn, the leaves suddenly black. When I close my eyes, I see my mother, mean for the rest of the day, rawing my back in the tub like she’s still doing dishes.

There’s much one could say about this poem, but what strikes me, personally, is how much it reveals about the author. See, I know Hafizah personally, or at least did for a time: she and I used to work together until she left her position as an acquisitions editor at Little A. I wouldn’t say we were close, but Hafizah and I had numerous conversations over the past few years, generally sticking to the work-issue-of-the-day; the titles Hafizah acquired tended to be both interesting and complicated, and it was my job to help with the complications. In our frequent-but-limited interactions, I knew Hafizah to be friendly, at times brusque, and brilliant.

Reading her book was akin to stumbling upon a coworker’s diary (or, more realistically, an outspoken social media profile), an exercise I found simultaneously fascinating and mildly discomfiting. Un-American is such a personal book of poetry—I did not get the sense that I was reading a speaker so much as the author—that this book lends itself to a review by someone who knows the author. Yes, I do intend to defend my flouting the “don’t review someone you know” rule.

Moreover, the literary world, and the poetry world especially, is nothing if not a small place, with only so many writers reading each other’s work, publishing each other, and attending each other’s readings. And hey, isn’t acknowledging that you know someone in a review of their work at least honest? Furthermore, maybe it’s a way of taking a stance against New Criticism, a way of arguing for a full-throated view of writing as coming from a real author with a real life that informs their work, versus a biography-agnostic, coldly objective close read of their work. Which, yes, is another defense of this review, however meekly academic and overwritten.

At any rate. Un-American is, per above, a book whose cover image is a painting Geter’s father, the artist Tyrone Geter, painted of Geter’s pregnant mother: is it the author or the author’s sister inside their mother’s swollen stomach in the painting? Does it matter? Either way, the painting, which is very good, making the book’s references to struggles Geter’s father experienced selling his work more poignant, can be viewed as a summary of Un-American’s content. The book’s three main characters—the mother who is the subject of the painting, the father painting her, and the (implied) poet inside the mother—are all there. Their relationship is reflected in the opening lines of “Naming Ceremony”:

My father, who spends most of his days painting pictures, says coming home to my mother stroking out was like walking in on an affair. Bending, he demonstrates how an aneurysm hugged her to her knees. Over and over, my father draws a loss so big it is itself an inception, a story he knows better than the day his daughters were born.

Though Geter’s father looms large over Un-American, it is the poet’s mother, and that she (and by extension her daughters) is a Nigerian immigrant to the United States, who looms over the book. Nearly every poem in the collection is in some way concerned with the poet’s mother and her mother’s status as a transplant, with her mother’s innate foreignness and longing for home. The opening lines of the book’s title poem spell this out clearly:

My mother transfers the last marigold from a pot to a patch of earth that she’s carefully bellied out beneath her, the dirt cool as a penny, her fingers tender with the bright petals as she demonstrates how what’s uprooted can return to solid ground, her colonial English helpless against her native tongue’s prayers. Allahu Akbar, my mother says as casually as she says my name.

Through the poet’s mother’s story, and the story which she gives to her daughters, Un-American—a book filled with non-English terms set in italics—examines what it means to be American. Just what that is the book never resolves; it seems to assume that the book’s readers will generally know or at least bring their conclusions about what it is to be American to their reading of these poems. As such, there’s an unresolved tension to Un-American, and as a collection of interrogative political/cultural poetry, it falls short.

But despite what the collection’s title, and the inclusion of four poems titled “Testimony” dedicated to Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner (“Bystander / footage, / marker 4:33, / I become / a broken bridge.”), might imply, Un-American’s focus and power aren’t rooted in political or cultural struggle, as opposed to a book like Citizen. Instead, its strengths lie in the overwhelming sense of closeness and intimacy that the collection’s poems exude, and in the many small delights to be found throughout: Geter’s mother’s whisper-like “a car revving its engine;” Nigerian names “familiar / sounds turned strange, / tightropes swaying, / in a colonial country.”; “my longing could drive a car.” Overall, Geter’s ability to convey such intimacy, the pleasantly suffocating familial closeness earned over a lifetime of loving, passing time with, and raging at one’s family, is what makes Un-American a marvel. That it attempts and frequently succeeds, in doing more is simply a bonus for us readers.