Why I Chose It: Michigan Quarterly Review Reader Maya Dobjensky introduces Donald Quist’s “The City Vs. MLK” from our Fall 2020 Issue.

When a black male journalist goes for a ride along with a white female cop, he reflects on his own latent fantasies of a career in law enforcement. Though Quist can’t help but grimace at certain aspects of policing, he’s also drawn to its myth of heroism and valor. But what does it mean to serve your country when your country doesn’t recognize your rights? How can you be a citizen of a nation that demands your allegiance at the expense of your safety? From Buffalo Soldiers to the 371st Infantry to the murder of Terence Crutcher, Quist offers an unflinching window into the violence inflicted on black men in the name of civic duty.

I chose this essay for its ability to weave seemingly contradictory threads into one tapestry, creating a multi-faceted exploration of race, violence, and patriotism. Instead of presenting neat answers, Quist leaves us with even more questions. And in these questions we learn an alternative language of patriotism. The act of challenging becomes a service in itself.

The City Vs. MLK

Maybe it was a lie by omission, my response when the judge inquired into my history. Standing for jury selection in the city’s case against Montez Lamont King, I denied having any relationship with the prosecution that might affect my objectivity. But when asked to divulge connections with the arresting officer, any history, I avoided glancing over at Lieutenant Horton, who sat on the witness stand.

If Lieutenant Horton remembered me from the ride-along we shared many months earlier, she betrayed any signs of recognition. She looked perfectly composed with her hair pulled back into a tight bun and her uniform so neatly pressed and fitted that it lent her the authority of someone with a higher rank, like a chief or even a general. But she remained polite and respectful of the central power in the room, and every response to the judge was followed by a quick and courteous “Your Honor.”

I’ve always wanted to embody that same composure, not just in the courtroom but every day I move through the world. I’ve always been attracted to a life in uniform, always admired the idea of being seen and regarded as someone heroic. Not like a superhero, although that is another fantasy. I guess what I mean is I’ve always wanted to be someone whose self-sacrifice would be honored and remembered.

And all I’m saying is maybe this predilection toward meaningful sacrifice and the desire to demonstrate what some might consider duty is why when asked by the judge if I had any history that might impact my ability to give a fair determination, I could feel my posture begin to mirror Lieutenant Horton, my back straightening, jaw tightening, as I looked solemnly at the head of the court and said, “No, Your Honor.”

Weeks prior to her detention of Lamont King during a routine traffic stop, I accompanied the lieutenant on a ride-along. I observed Horton respond to three incidents Halloween weekend. The first, a domestic disturbance between two drunk lovers.

We arrived in the cop car to find an African American woman wearing a holey, navy sleeping gown, a burgundy fleece pullover, and lime bedroom slippers. She stood waiting for us in the street in front of a weather-stripped shotgun home, sloping on its sinking foundation.

“Wait here,” Horton said. “Don’t get out no matter what.”

She and I had only just started the evening together. I had met her at the police station, and we had fumbled and smiled through awkward pleasantries and politeness common between two people not entirely sure about the other’s motivations. While I’m sure she was suspicious of me, as a writer of color and former local journalist asking to accompany a police officer patrol, she didn’t ask me what prompted me to do a ride-along. And I didn’t ask what would lead her to volunteer to share her work with me. When I first discovered I’d be paired with Horton, a woman, I felt a sense of relief. I knew I’d feel more comfortable around her than a male officer, especially a white male officer, and I accepted that my comfort around Horton involved underlying misogyny—the fact that, at three hundred pounds and five feet, ten inches, I could overpower Horton, a head shorter and less than half my weight. At the time, I didn’t think about the ways my size, gender, and race might have also made her feel less comfortable.

So, when she told me not to leave the car as she prepared to respond to a potentially violent situation, I experienced a surge of protectiveness and guilt out of a dereliction of chivalry. I fought the urge to go with her, nodding to show I understood her authority. I became hyper-aware of the straps of the seatbelt binding me to the passenger seat of her police cruiser. She slammed her door and approached the woman standing in the road. Dusk was beginning to settle in, and above the trees lining the street, a full moon was becoming more prominent against gradients of gold and blue. Officer Horton’s voice squawked through the radio mounted to the dashboard—numbers and her current location broadcast to this and other cop cars in the area. Alone in the cruiser, I noted the minimal accessories to Horton’s car. On a handle that jutted out of the cab and through the driver’s door to operate the searchlight mounted above the side mirror, Horton had hung three additional pairs of handcuffs. The stark reality that there might be a need for the cuffs clashed with the only accent of color in the car, a glittering butterfly-shaped hair barrette clasped to the sun visor above my head. Bedazzled with sparkling rainbow gems, the large clip could keep Horton’s thick, dark hair pulled back tightly. The playful barrette led me to wonder what Horton is like out of uniform. I tried to imagine her smiling and her laugh, perhaps a low, hacking bark like a series of coughs, or maybe she snorts when she finds something really funny.

Then I caught the clack-pop of a screen door and then the flash of a human body blasting out of the front of the shotgun house. The body—a shouting woman, stumbling barefoot—barreled at Horton and the civilian in the street. I rose bolt-upright in my seat, watching through the windshield. Horton held up a flat palm in front of her, and the belligerent lady halted a few feet away, still screaming at the woman in fluffy, lime slides. Her ashen dreads shook as she yelled. The grey ropes sprouting from her head matched the patches of dry scales covering the skin of her arms and legs revealed by her too-short muumuu dress. I guessed that she was the reason we had been called here. The pair might have been in their fifties or perhaps much younger and aged by poverty. They didn’t resemble each other. Cousins maybe. Perhaps roommates. Horton watched the two of them argue for a couple of minutes. Horton rested her hands on her waist, just above her utility belt, her fingers inches above her Taser and gun. Eventually, Horton raised her hand out again and calmed them. As she spoke, I could see the shoulders of the civilians slowly drop, and the taut cords of their necks relaxed. The women nodded at each other, looking upset but somewhat in agreement. They turned away from Horton and returned to the house grumbling to each other, content enough with the threatening peace Horton had brought between them. Once they returned inside their property, Horton turned to the cruiser.

I waited for Horton to settle into the driver’s seat to call some words and numbers over the police radio before asking, “Is everything okay?”

“Oh, yeah,” she said. “Just a couple fighting. One got a little too drunk.”

And she smiled after saying that last part, recalling something she didn’t share with me. Her lips twisted into a sly half crescent crashing into her right cheek. She laughed a little too, a quick goofy chuckle I could never have pictured.

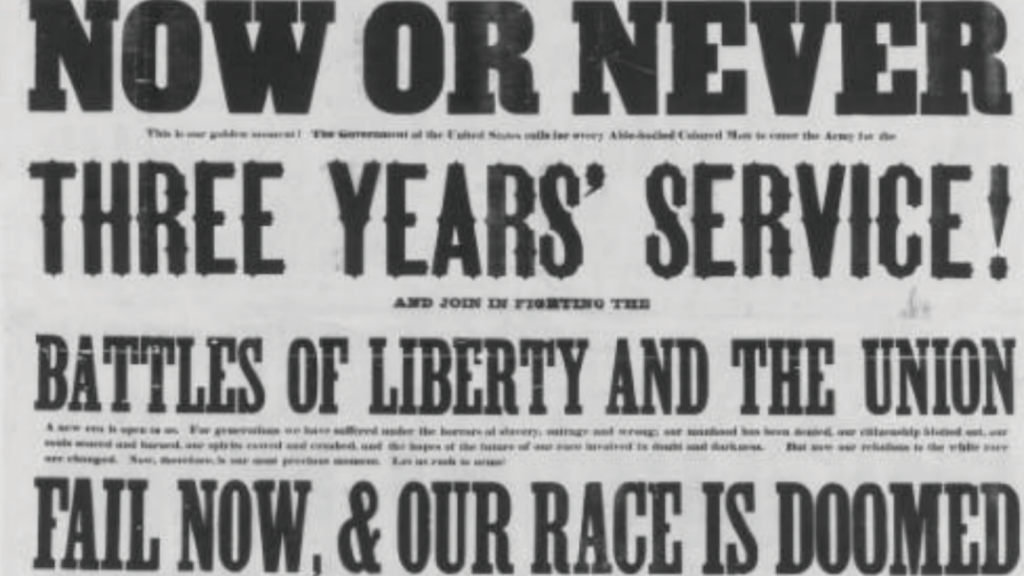

I’ve been thinking a lot about the history of folks like me supporting ruling powers at home and abroad. Oftentimes this support came at the expense of other people of color, like the 10th Calvary Regiment of the United States Army. Dubbed Buffalo Soldiers, the 10th Calvary was comprised of African Americans. They served in the American Indian Wars from 1866 to the end of the nineteenth century, helping the US government’s violent expansion through the Great Plains and the Southwest.

On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat torpedoed a British steamship and prompted America’s involvement in World War I. Soon the US Congress passed the Selective Service Act, initiating a draft requiring all young men, regardless of race, to register for military service. The decision to include African Americans in the draft was largely based on President Theodore Roosevelt’s positive experience leading Buffalo Soldiers into battle against Native Americans. Roosevelt’s opinions swayed Woodrow Wilson, who believed African Americans were too unintelligent and lacked the discipline needed for war. W. E. B. Du Bois was one of many African American leaders and activists who saw the draft as a chance to prove folks like me deserved racial equality. Hoping the US government would see our loyalty and service to their country, Du Bois encouraged men like me to say, “first your Country, then your Rights!” Nearly 400,000 men like me were registered and inducted into military service and encouraged to show their best devotion to the nation. We should fight hard, demonstrate our ability, and maybe when the war was over, our lives at home in the United States would become fairer and more balanced.

Some of those African American World War I veterans, soldiers of the segregated 371st Infantry Regiment, are buried in the Saint John AME Church cemetery outside of my mother’s hometown in Hartsville, South Carolina. I drive by it whenever I visit friends and family in the area. The crumbling headstones share a resemblance to the broken monument constructed by the French in the village of Séchault to honor the men of the 371st Infantry. In pictures I’ve Googled, the monument shows damage from shell bombings during World War II. The cracked stone testaments on both sides of the Atlantic are a reminder of failed American social bargains, a broken promise that if folks like me put our country first, our rights as American citizens will be fully honored.

In the seconds before I said, “No, your honor,” I did not consider that I was following a desire similar to that of many of those Buffalo Soldiers or members of the 371st Infantry: to prove my value and loyalty. I feared losing a chance to serve a civic duty because I saw an opportunity to feel a part of my own nation. After being a juror, maybe I could start to envision myself as a fuller citizen protected by the country and its laws and not a potential casualty of the state.

Lieutenant Horton and I made circuits around the city, a giant, winding chain of streets linking the edges of gated communities and low-income housing developments. The cruiser crept through one of the HUD apartment blocks, and kids playing in the parking lots froze as Horton and I rolled past. Basketballs slid into storm drains, and young girls and boys retreated slowly but steadily off the asphalt and onto the sidewalks and segments of brown grass leading to the shelter of their buildings. I noticed how the kids moved without taking their eyes off the cop car. Their bodies carried them away while their necks twisted to keep Horton and me in their sight. One little girl tripped over a curb but popped up onto her feet, her eyes on mine as Horton explained how people don’t understand half of what officers actually do. “We aren’t trying to be jerks. We’re here to protect and serve. Yeah, there are a few bad cops, but it’s not all of us.” We rode by a group of teenage boys gathered and laughing on the corner of one of the apartment structures. Their joking paused until they were in the rear-view mirrors of the cruiser. “It’s not fair, right? For all officers to be judged because of a few. That’s what I call prejudice. The majority of us just got into this to help people.”

I asked Horton why she decided to be a cop. She told me she used to date an officer. She was in school to become a nurse then. Her boyfriend would often take her on ride-alongs. Horton found she enjoyed the driving, the hours, the workload, and the camaraderie between the officers. “It was fun,” she said, and I caught a reflection of my grimace in the passenger-side

window. I didn’t like the thought of law enforcement being fun.

She asked me why I’d come on a ride-along. I said something about how I thought citizens had a duty to learn as much as they can about their local law enforcement. I said something about community-oriented policing. And then, after several seconds of her silence, I confessed that some part of me has always wanted to protect others and serve communities I belong to. “In another life,” I said, “I might have become a cop or a soldier.”

Horton told me I could join the force. The police department is in need of new officers, especially men of color, she said. She told me I could do a lot of good. I could inspire others.

I didn’t ask who the others were or what I might inspire in them.