Eduardo C. Corral earned degrees from Arizona State University and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His debut collection of poetry, Slow Lightning (2012), won the Yale Younger Poets Prize, making him the first Latinx recipient of the award. His second collection, Guillotine (2020), was recently longlisted for the National Book Award.

Note: The following is a transcript of an interview conducted over Zoom. Edits have been made for clarity

David Freeman (DF): In 2014 at AWP, you explained that you wanted your second book to be a “radical departure.” But more recently, in a talk with Ocean Vuong, you said that your understanding of that has changed. Could you talk a little bit about the development of Guillotine and how your relationship with it has changed over time?

Eduardo C. Corral (EC): For a few years after my first book, Slow Lightning, came out, I was traveling across the country and giving readings for that book. And during Q&A’s whenever anyone would ask, “What is next for you?” I would always answer, “I’m not sure, but the next book is going to be a radical departure, either at the level of language or subject matter or maybe both.” I was almost saying, “If you don’t like Slow Lighting, don’t worry! Maybe you’ll like the second book.” [laughs] Or, “I don’t think I got it right. I don’t think the poems are that interesting, but maybe, for the next book, something will click.”

And I do believe now, looking back, that there was some kind of anxiety and doubt fueling that answer. Unfortunately, if I’m really honest about it, I felt anxiety and doubt about the work itself. In other words, that the border, queerness along the border, and these intersections that happen in the borderlands in this country were only good enough material for just one book. I think that was also buried there, unconsciously. It had to be unconscious because the idea repels me when I say it now [laughs].

I also wanted to sound like I was always on the lookout for new in my own work, that I was always trying to enact Pound’s adage to “make it new.” But I didn’t realize, until I began working on the second book, that making it new also meant returning to your obsessions and finding new ways to enter those obsessions and finding new ways to exit those obsessions. So, in a sense, anything — any obsession, any subject — is inexhaustible. It is up to the imagination. Therefore, when I started writing some of the poems for the second book, I realized how adjacent they were still to the first book, and how close they were still to my obsessions, to the subject that resonates with me, to the language that pulls me along into its gravity. And then I realized, “Okay, this is what’s going on.” So I was very quiet about it. I didn’t say much about the new material for a while. I often misled people, saying I was doing a project I was not doing so that they wouldn’t ask deep questions about what I was doing because I didn’t want to feel that kind of intrusiveness in the new material.

DF: I know in some interviews in that time you had spoken about working on a book-length project about the outsider artist Martin Ramirez. Was that an effort to throw off interviewers, or did that research inform the new work?

EC: It was it was both! [laughs] It was a way to throw others off but then, when I started researching his life, and his art, I was inspired. I did draft a few ekphrastic poems inspired by his art pieces, his collages, his drawings, which were all handmade — even his art materials were hand made. He did charcoal work with the burnt-out tips of matches. He pieced together paper for his collages from hospital gowns. He used paper from his living space when he was institutionalized. So, yes, it began as a kind of ruse but the more I dove into it, the more his art and life resonated with me, especially his art.

But also, I started thinking about persona more deeply. Because his life is not my life. I started to ask, how can I enter his point of view? And I think those questions prepared me, prepped me, made me more open to persona, to the other voice-driven work, which makes up half of Guillotine with the sequence, “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel.” Just thinking and dwelling on the possibility of having a persona dominate my second book prepped me and prepared me to allow these other voices to arrive, and made me eager to work with them and to hear them and to try to staple them down onto the page.

DF: I was going to say, even though the first thing someone might think when reading Guillotine is that it’s a very personal collection, there are a lot of voices in the work. There are the voices scratched on the water station barrel, as you mentioned. But there is also a border patrol agent, a man who is forced to run drugs, etc.. I’d love to hear how you approach voice as a writer? How do you locate it?

EC: I don’t have to know everything completely about a voice if a persona approaches me, if it roots itself in my imagination. I just have to know the urgency behind the voice. I don’t need the biography of the voice, i.e., “I was born in…etc…. I went to school in…etc.” I don’t need that kind of an outline of a life. I need the reason why this voice was pushed into utterance. And once I figure that out, once I sense it, that’s enough for me to work with that voice. To imagine that voice. Because it’s a lyric poem, so it’s a glimpse, it’s an observation or an approach to a specific moment in the speaker’s intellectual and emotional life. It is not a full narrative.

DF: In addition to the realized voice, there’s also a sense that the book’s forms have been lived in. I’d like to ask you about the title poem of the collection, “Guillotine,” because it’s one of several poems in the collection that uses the triadic step.

EC: Yes, the William Carlos Williams line! The triadic stepped line. When he invented that — when he indented the line three times — he said he imagined that form as the perfect container for American speech. That it would catch its swerves and pauses. And that phrase has always stayed with me. “Swerves and pauses.” And I’ve found it very helpful to simultaneously enact and isolate some of the voices in the book, even the more intimate “I” voices.

DF: It seems so fitting for so many of the poems. It has a motion, but it also has such a firm shape to it.

EC: It is both fluid and static simultaneously, which I like. I like that tension. Tension is very important to poetry, to all artistic output.

DF: In addition to the triadic step, there are a variety of forms in Guillotine. What is your process is for arriving at a form for a poem? When do you know a poem is in the right shape?

EC: In Slow Lighting, no shape is repeated. So, every poem has its own distinctive shape. I was very interested in visual variation for that book. Because the visual conveys meaning at the end of the day, and I wanted to structure the shapes to underscore or amplify something that was going on in the work, whether that be a specific use of the language of a poem or a poem’s aesthetic, or its obsession. For example, the shape of the poem “Caballero” in Slow Lightning was a shape I stumbled upon playing with language. Years ago, after a reading, somebody approached me — I think it was a graduate student — and they said that if you turn the poem horizontally, the stanzas look like hoof prints. And that poem is, of course, about horses. And I said, “I never saw that!” so I love those moments when the unconscious is doing its necessary work.

But, since I knew that no pattern was repeated in Slow Lightning, I wanted to break that pattern for the second book, Guillotine. I wanted to have a baseline structure, such as the triadic step lines. I wanted to have a baseline, a foundational shape, so as to break my pattern from the first book. I think it’s very important for poets to recognize their patterns — whether it be at the level of language, stanza, subject matter — and break those patterns here and there. The secret to poetry is pattern and variation.

I have a strange and labor-intensive drafting process. My first draft is in couplets, the second is in tercets, the third is in prose poem paragraphs, the next is a column of text, and the next is an open field arrangement where I scatter the language across the field of the page. So I pour language into new containers, and I make sure that each of those containers has a new line length, so I make sure that I’m forced to rework the syntax and diction of a line, which allows me to put more pressure and pressure on my lines. This way, I can get them as interesting and rich, and engaging as possible. And also, because I’m pouring the language into new containers, new shapes, I invariably start playing with shapes. In other words, I imagine other visual possibilities with the language. That’s how the shapes come to me. By the time I have poured the language into the eighth, ninth, eleventh container, I have kind of pared down the language to what it needs to be, or what I think is essential — “the right words in the right order” to quote Stephen Dobyns. Then it becomes a bit easier to find the shape because the language is there. And that explains why it took nine and a half years to write Slow Lightning and eight years to write Guillotine. [laughs]

DF: I think one of the great things about taking that time with your work is that it seems like the book is still revealing things to you years later. It’s interesting to think that maybe Guillotine will reveal things to you years later that you don’t notice now.

EC: I know it will. That’s one of the best things about being a poet, and having your work published, is that a reader does so many things with your text. An engaged reader who has an interest or, even better, who has questions about the text, about the word, the image, the line — their mind will alight in some interpretation, some point of view, that is often wonderful, that shows you something you didn’t see when you were writing it. Which is a great gift that readers give to writers. They’ll say, “Oh, I noticed this.” or “Oh, did you mean to do that?” or “Was that intentional?” And if it was not my intention, I never fake it. I never say, “Oh, of course, it was. I’m brilliant. What do you expect?” [laughs] I always say, “Oh, I never realized that. Thank you. Thank you.” because I want to acknowledge that labor and that interest on behalf of the reader.

DF: There is a lot of what I would call intertextuality in Guillotine. You have one poem whose title is taken from a Gonzalez memoir, another poem, titled “Around Every Circle Another Circle Can be Drawn” has its title taken from Emerson —

EC: And St. Augustine is also rephrased into that poem.

DF: Right! So, it seems like there are texts that are directly at work in the poems. I wanted to ask how those texts interact with your work? How your life as a reader informs your life as a writer?

EC: Before I’m a writer, I’m a reader. This is my primary joy in life: to read and think about what I’m reading. And when something captures my interest — a phrase or an image — I put it in my notebooks. And if it resonates with me, it stays with me. And invariably, if it stays with me organically during the drafting process, if that thing, that language is still resonating inside of me, it will sometimes get put into the draft. And if it survives the revision process, then it stays! I’m open to that. I don’t say, “It’s not my language. Not my image.” Of course, I always acknowledge and make sure people know where and when the theft has occurred [laughs], but I’m open to that. I’m a reader, and I’m deeply moved, shaken by other people’s language and ideas and concepts and images, and if I can borrow them for a while and give them a new life in a different kind of context, refreshen then or trouble them or complicate them in certain ways by putting them into my work, why not? This is not a new concept, but it’s a concept that I love because it makes poetry more approachable and more accessible. I think of poetry as a conversation that started way before me that I am now as a practicing poet, that you are joining as a practicing poet, that will continue without us.

DF: You’ve mentioned that during the process of writing Slow Lightning, there were lots of notebooks filled with your notes—

EC: Boxes and boxes of them.

DF: Did that process continue for Guillotine?

EC: There are boxes and boxes of those! [laughs] There is a bit less. Slow Lightning was a first book and had an MFA thesis written before it, and because of that, I generated a lot more material and drafts than I did for Guillotine. Guillotine was a more concentrated effort. Once I figured out the contours of the second book, I was very focused on those contours. In the nine and a half years it took me to write Slow Lightning, I must have written enough poems for two manuscripts. But I jettisoned a lot of things. A lot of things were drafts that never went anywhere. And I think that was a big difference for Guillotine. For Guillotine, notebooks were present, but the difference is that I started incorporating my iPhone into my notebooking practice. So that took out a third of my notebooks. [laughs] But notebooking remains the root of my creative practice.

DF: Does the iPhone have any effect on your practice at all?

EC: For me, it’s such an obtrusive thing and an unobtrusive thing. It’s there, and I notice it, but also, I forget it there’s. It’s just become such an ordinary fact of life in the Western world. And because it’s there all the time, I notebook with it. I never draft in it. I know other writers who draft on their devices, but I can’t do that. But I notebook in them. But I have a rule for myself. I have to write, by hand, at least 9 to 10 versions of a poem, drafts of a poem, before I leap to my laptop. I have to have that hand contact before I leap to a device. However, that’s also very generational. A lot of my graduate students draft and revise just on their laptops. Because, for them, it is their pen and paper.

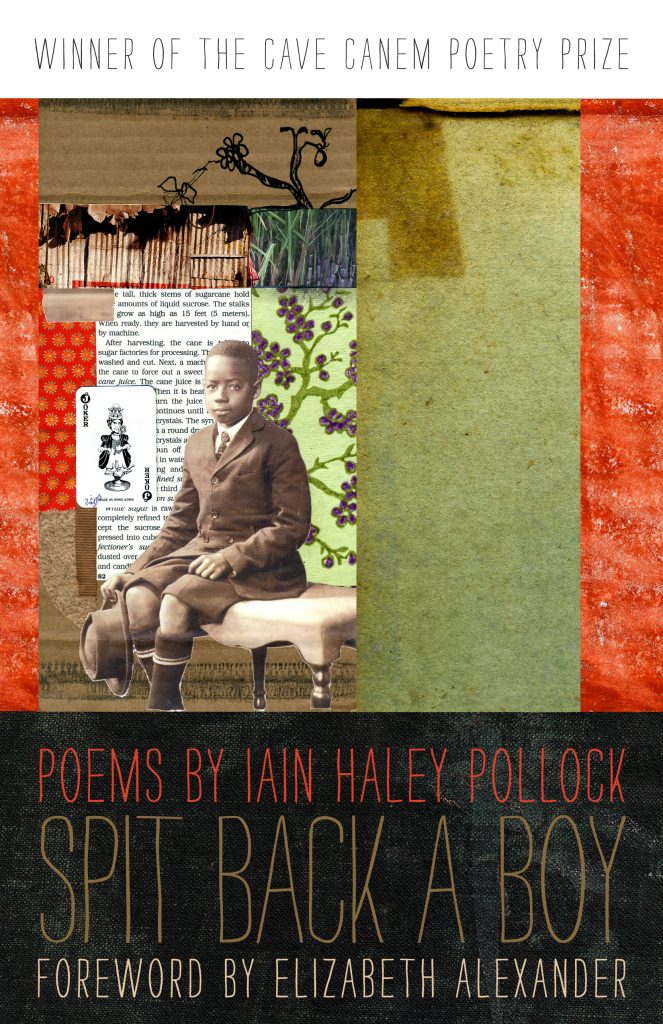

DF: On the note of objects, the book is such a beautiful object itself, and I know you’ve been very vocal on social media about how amazing the cover is.

EC: I love my cover. [laughs]

DF: How did you arrive at it?

EC: I pick the covers for my books. I’ve been very lucky to work with two fantastic presses—Yale University for my first book and then Graywolf my second book. The design team at Graywolf presented me with a few options, but I didn’t feel the options that were presented were right for the work. Something wasn’t right emotionally, intellectually, or for the voices present in the work. When I realized that I would probably have to find something for Guillotine, I immediately thought of this artist.

Felipe Baeza is the artist for the cover, and I knew his work, and I love his work. I have to give complete thanks and gratitude to Graywolf Press because they were so helpful to me. They said, “Okay if you don’t like this, how can we help you? What can we do to make this better?” They’re an absolutely wonderful press to work with. They’re very attentive to their authors, with everything. So, I’m very thankful for that. But I knew this painting would feel right to me. The minute I saw it, I knew it felt right. So, I bookmarked it, and then, when I needed it, I pulled it up. I frantically emailed the artist, and he answered back, “You can have it.” He was very sweet.

I love so much about it. I love the colors. It also looks like a religious icon, a bit. But it’s very queer too. And I love the gaze of the figure. The figure is staring at the reader who approaches the book. I like that gaze. That gaze is very important to me. It can be a threatening gaze or a seductive gaze, but I love the gaze and the agency in that gaze. And that’s very important because there’s an agency in the voice-driven work, where immigrants are moving through the desert, whose voices I’ve tried to capture on the page. There’s agency in their voices because they’re thinking, they’re feeling, and that is power. That is agency.

DF: I know visual art is very important to you. In the book, you mention photography. Can you speak to if your relationship with visual art has informed your work at all?

EC: In my heart of hearts, I would rather be a visual artist than a writer. [laughs] I would! But unfortunately, David, I have no skill set with the visual. I can’t draw. I can’t watercolor. I just don’t have the ability to express myself in that medium. But when I go to art colonies — like Yaddo or Macdowell — I love hanging out with the artists. I love visiting their studios because their process is so sensory-rich. All the paint. All the stretched canvas, the palettes, the materials they’re working with—their sculptures. I love how sensory-rich the process is. We don’t have that, for the most part, as poets. We get, you know, our laptops and a notebook. The closest you can get is a scented pen. [laughs] That’s one reason I yearn to be an artist and to be surrounded by a sensory-rich process. I find it quite amazing.

And the only secondary visual practice I have is taking photographs, usually when I travel abroad. When I go to Spain or Italy, or France, I love to take five to eight photographs a day and post them on my social media accounts. People often say, “I like it when you travel because I know we’re going to get a lot of photographs.” So, they can live vicariously through my photographs. Which, of course, I also love to do when my friends travel. I love to look at their photographs.

But you know what? One of the reasons I take so many photographs is because those photographs become shortcuts to me. I can immediately return to the moment I took that photograph, where I was, what I did before and after, what I was thinking and feeling in that moment. It’s a visual shortcut for me that I love because it brings me back to my travels, to my moments. Something about the image takes me back. Which I think kind of explains why I’m so image-driven because there’s something about the image that kind of positions and situates me and allows me to return to emotional, intellectual states. This is why I also yearn to be a visual artist because I want to do that myself on a canvas or in another material. Imagery — be it a simile or a photograph or a metaphor — really resonates with me. It becomes a shortcut: a shortcut to certain intellectual, emotional states, which is important to me.

DF: On that note, I noticed a lot of the poems in Guillotine are very located. You already mentioned the sequence, “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel.” There’s also a poem titled, “In Federico García Lorca Park.”

EC: Yes, Granada, Spain. A beautiful, beautiful city. I actually had dinner with Federico García Lorca’s niece. A Spanish poet knew I was visiting, and he asked, “Do you want to meet Laura García Lorca?” And I said, “you better believe it!” So, me and a group of her friends had a very lovely dinner. She spearheads his literary estate throughout Spain, and funnily enough, her husband is one of the foremost Lorca scholars. It’s all in the family — the Lorca industry, so to speak. It was fantastic.

I remember his house is located in the park in Granada. The park is named after him. I spent maybe fourteen days in Granada, and I went to the park every day. To sit, and walk, and observe. And David — I am not going to lie — I went every day hoping for communion, or some kind of contact with Lorca’s spirit or ghost or presence. Lorca means a lot to me. As a writer, as a queer writer. His work just resonates with me. It’s so clean and precise. It feels immortal. It feels eternal. There’s something about that work that just resonates, unfolds, stays fresh, decade after decade. There’s a reason why he’s one of the world’s most translated poets. His work, his imagery resonates no matter who you are or where you are. But I wanted something special. Something straight out of the movies! But nothing, of course, happened, but some of those lines came to me, and I just stapled them down. I said, this will be enough for me, this little gift of a poem will be enough.

DF: That poem is wonderful, and it does feel like a gift. It’s also in a form I haven’t seen before where every other line is italicized. Can you speak to that form?

EC: It’s a variation of a call and response. The italicized language feels like a response to the line above it. And in my heart of hearts, I also imagine that was me forcing Lorca to speak back. I was trying to force this moment.

DF: And it feels fitting for the book. Because there’s a lot in Guillotine about desire, that’s unrequited.

EC: One of the huge differences between Slow Lightning and Guillotine is that, in the second book, there is an emotional vulnerability that I don’t see or feel in the first book. People also find the first book very vulnerable and very emotional, but what people don’t know is that the details are often very fictive. For that book, I let my imagination go where it needed to go. For example, my father never grew up in Colorado. My mother never gave me a pack of cigarettes. But the emotional resonance of those poems is true. In Guillotine, of course, all that happens on the page did not literally happen. I did not actually pluck a mole from my skin to form a black rosary. But they do cleave a bit closer to the actual.

In the poem “Autobiography of my Hungers,” there was that moment in the bar at the booth, which is very central — not only to me as a person — but for the second book. So that happened, and it became important to the book. That poem acts as a keystone and supports the other “I”-centric poems. And that’s what I wanted to risk in the second book: vulnerability, rawness. And there might be too much! [laughs]

DF: And the reader can feel that vulnerability from the very end of the first poem of the book, “Ceremonial,” which ends with the line, “Here I am.” There’s such an announcement that the central speaker of the collection will be present.

EC: I placed that poem at the beginning for a couple of reasons. One, because that poem is very emotionally complicated, and if it were closer to the other emotionally rich poems, they would just kind of suffocate each other. Spacing out these emotional poems, it gives them room to emote, to breathe. And the ending, “Here I am,” was me trying to say to myself, “Yes. Risk this vulnerability. Risk this. Put it on the page. Say it the way you need to say it. Not as a memoir, but let your imagination have its way with it too.” And to end that poem on “Here I am” — with one person asserting themselves — helps that poem lead to the Testament poems. You get one utterance, one human cry, and then that cry becomes a chorus of voices. And that was important to me structurally—that you enter the book through one voice, and you move through many other voices to return to a single voice. A movement through a chorus, a community, before arriving again at the lyric self.

DF: I just have one more question for you. A lot of readers and staff of the Michigan Quarterly Review are in graduate school. You’ve said before that a student should not focus on their thesis becoming their first book. What do you think the best thing an MFA student can leave a program with?

EC: The first part of my response is that I always tell my graduate students, the best thing I can do for you is to help you put a writing practice into practice, to create something that will sustain you after graduate school when you don’t have this structure or this community. Ask yourself, how are you going to move through this world as a poet after leaving this MFA program? I think that’s very important. How do you see yourself as a writer and a poet? How do you move through the world as a poet? These practices, those strategies, sustain you, and nourish you, and challenge you in your post-MFA years. I often think that many people can’t articulate their writing practice. They say, “Oh, I read and write,” but those are the givens of our art. How do we complicate that? How do we pay attention, how do we complicate, how do we trouble our attentiveness to reading, writing, looking, and moving through the world? In other words, what’s your creative practice? How are you open to the world?

And then, when it comes to the thesis, I have a lot to say. I was a horrible MFA student for many reasons. Of course, I went to a horrible program, so that horribleness rubbed off. But I was writing poems to impress my classmates and my professors. And I can sense that every once in a while, when I guest teach, or even with my own graduate students, that they want to impress their cohort or their professors. One of the things I always say on the first day of class is, “You got into the program. There’s no need to impress anybody. You’re in. Now use these two years to take risks, push yourself, fail, and ‘fail better’ to quote Beckett. Use these two years to play to experiment with your language, your process, your drafts, your revisions.” And that’s very important. I wish I would have had that kind of permission, that kind of possibility as an MFA student. I was hell-bent on writing my first book in those two years. But how was I going to write my first book without mentorship from a professor? Without any kind of encouragement or challenge to the work? I had none of that. But for my students, I would say that, for those two or three years, you need to not center product or try and produce a book. You need to interrogate your process. You need to risk, risk, risk.

And I do want to say; it’s easy for me to say that. I’m a poet that’s been amply rewarded. Even though it took me a long time to get to my first book, it was well-received. So, I know this is a very privileged place I’m speaking from. That said, I have lived and enacted my advice. Writing the first book, writing the second book, I centered my process. I waited. I was patient. I didn’t push my book out into the world until I knew it was ready. I resisted the pressures of the poetry business. I resisted the advice and pressure from my friends and mentors. I have walked that walk, which is why I feel comfortable giving this advice.