To describe the greatness of some athletes, David Foster Wallace said, you need to resort to metaphysics since “we’re talking about those rare, preternatural athletes who appear to be exempt…from certain physical laws.” In Be Holding, a masterful, book-length poem written in stream-of-consciousness couplets, Ross Gay wants his readers to know that Julius Erving – aka Doctor J – was one of those athletes.

Early on, Gay seems to be writing an extended ode to “The Doctor,” but the poet takes advantage of Erving’s super-human body control and hang-time while finishing The Lay-Up (hoops’ fans love these designations: Michael Jordan gave us The Shot; LeBron gave us The Block) – a truly amazing move during the 1980 playoffs that would have made Isaac Newton doubt the rational laws of the universe – to contextualize Erving’s greatness. Erving sees more than anyone else on the court, recognizing that the basket is “an iron hole drawn in space,/and therefore implies a window/though the key makes it also a door.” Even in a small space packed with “trees” (big men), Erving sees possibilities everywhere. So does Gay.

Writers can also transcend the laws of time and space, and in recognizing that “nothing happens/only when it happens” Gay is quick and keen to make connections between his present obsessions, such as this YouTube basketball footage and the past – the historical past (nodding obliquely to the profound resistance of the Flying Igbo), to sharecropper ancestors and, ultimately, to his parents. In other words, the people to whom he is most beholden.

One of the great pleasures of this book is hearing how effortlessly Gay jumps from register to register. He writes with the animated force of a super-fan one minute (describing a player he coached who can “pump fake, [take] two/dribbles and fly to the rim”; or cheering on Doc against “Bill Fucking Walton”) and speaking in the next with assured erudition as he references Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, the soprano trill of Minnie Ripperton, Frank Lloyd Wright. Gay also sails so smoothly from one subject to another, in this single-sentence saga, that you come to believe all these stories (and millions more) were right there all along. Writing about one of Dr. J’s opponents, Jamaal Wilkes, Gay jumps from Wilkes’ nickname –“Silk” — to his own basketball playing days:

[Silk] “gathered from captive worms, fed mulberry leaves, my court name was Beast for what it’s worth…”

n a particularly brilliant, 8-page section of the poem, he considers a 1975 photograph in which an African American woman and her goddaughter, a very young girl, fall to their apparent death from a fire escape. Because the names of the victims were withheld from the title and caption of the photo, Gay withholds the name of the photographer here who “unlovingly” held a camera “behind which/ was a man/in a building across the way/in a window/he found open to the horror/who would win a Pulitzer Prize for spot photography/for shooting the woman/and the little girl/capturing her/staring at us/staring at her death.”

Gay’s loaded language here indicts the photographer for his complicity in watching the destruction of these bodies, for aestheticizing this horrific violence. Later, Gay watches watchers in a “museum of black pain”: “mostly white students” and “their white teacher” who are mostly not noticing:

The black people falling forever Framed on the pristine wall Becomes itself A war photograph

Here Gay also wars with himself since he knows that by relating these scenes of violence and disregard he, too, has become a sort of “docent/in the museum of black pain.”

One of the main subjects in Be Holding is the business of witness: what does it mean to bear witness, to “behold”? Turning a tragedy, such as the “fire escape fall,” into a 2-D rendering can dehumanize and diminish. Yet, what of Gay’s own deeply sympathetic and accusatory reading of that photo? What of his expansive “reading” of the Dr. J footage – and the bird’s eye photo of Erving he provides – as an avatar of beauty and liberty, politics and possibility? So much depends on who is doing the beholding.

Later in the book, for example, returning to Dr. J, the poet thinks that Doc is “listening to some music/no one else has yet heard…/which you would likely miss/if you didn’t watch the clip/as many times as we have tonight.” But who is this “we”? We readers are watching Gay watching a video clip as he curates a personal museum exhibit that is part memoir and part historical monument. He is not only curator but also projectionist in these “private screenings” – projecting his personal life on the images he confronts — and we are left to watch in amazement as he unspools these various reels in an uninterrupted, virtuosic montage. That’s what is so impressive here: Gay’s lines have such propulsion as we watch his generative mind in flight.

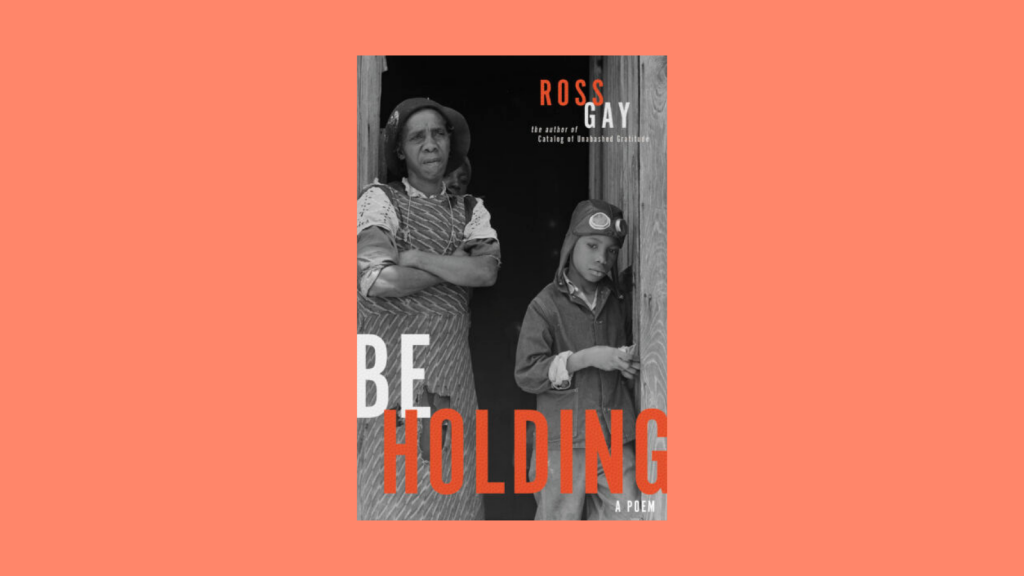

In the Dr. J photo, he sees “the flight in it/to be a window,/or a door/a door/which right now I will point you to,/a real door in a real photograph/I found looking through the WPA agriculture photos/at the Library of Congress.” And here, the poem is accompanied by another photograph, that of a grandmother standing proudly in a doorway with her son (also un-named), a young boy with flight goggles on his head, whom Gay infers is also dreaming of flight. This is also the cover photo of the very book we are holding.

The doorway in that photo serves as another portal through which Gay’s thoughts fly: to his great grandfather, a sharecropper, whose body was “loot, and his life, loot,/ his life was theirs,/ like the crop,/ like the land,/ they could be/ thrown overboard/ for the insurance”. And to his father who, after being drafted, flew to war, “tr[ying] sadly/to prove himself/a citizen,/not cargo loot/thrown overboard.”

Ultimately, this book is a poem of gratitude – of all the people to whom Gay is beholden. And Gay’s gratitude is evident throughout (this book may also feature the longest “Acknowledgements” section in any book of poems I have ever read). Perhaps most of all, he feels beholden to his parents: his mom, a white woman, whom he beheld having to endure disapproving sneers at the grocery store with her two biracial children, and his father who showed his children “how to fly…by reaching toward/what you love…the reaching/that makes falling flight.” In other words, the practice of “holding each other.”