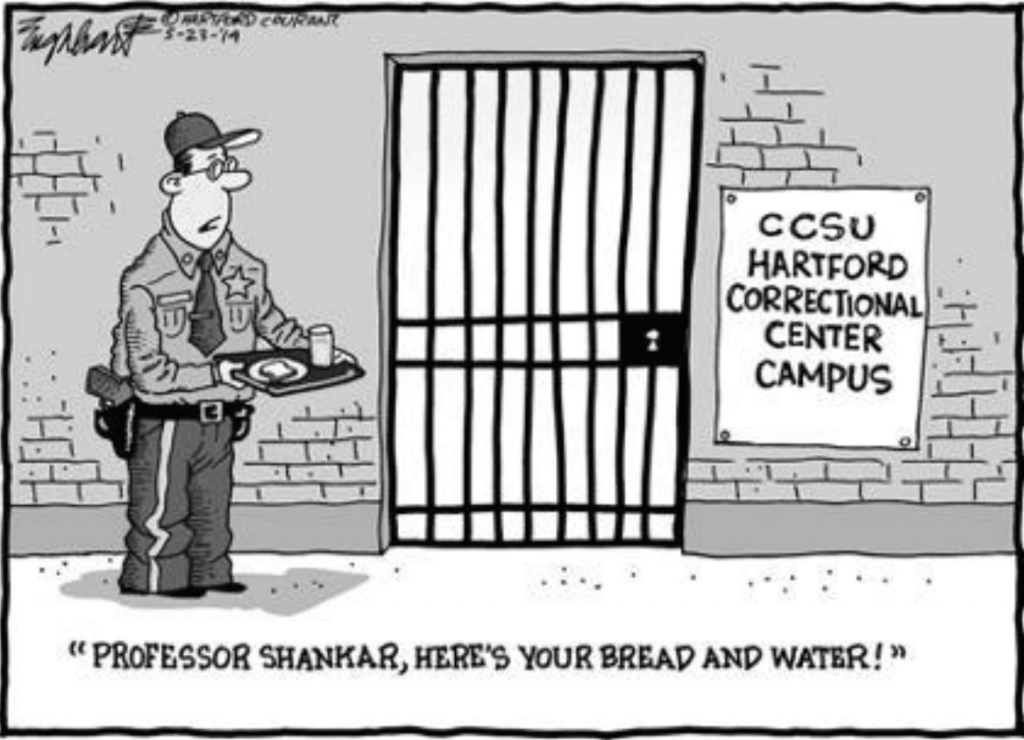

In 2013, Indian American poet, editor, and professor Ravi Shankar was sentenced to a 90-day pretrial detention at Hartford Correctional Center, a level 4 high-security urban jail, for violating his probation for a DUI offense by driving while his license was suspended. During that time, he became the first American academic to be promoted while incarcerated, a decision that inflamed the local media and ultimately led to his resignation from Central Connecticut State University. His forthcoming memoir Correctional (University of Wisconsin Press, 2021) is about that time, both what led up to his incarceration and what revelations came out of that experience. This excerpt comes from the middle of the memoir.

I emerge from the caged elevator to the basement of the courthouse where my freedom has officially been surrendered. I’m searched for the first of many times that day by a brisk marshal who pats me down like a furniture appraiser looking for defects in an antique bureau. He confiscates my silk tie, my books and shoelaces, none of which I will ever get back, and leads me into a communal cell that smells of sour milk. I’m about to begin serving my time in jail.

My first resting place at Hartford Correctional Center is Dorm#4, which sleeps 60 men on 30 bunk beds. The space that three bunks make together is your cube, and it constitutes the area to which you are relegated to for most of the day. During “count,” you remain motionless on your bunk until a full head count has been taken and then cleared. The COs mainly stay in an area called the “Bubble,” which has telephones, request forms,

toilet paper, monitors for the cameras always running, and the intercom system by which they make announcements and issue threats.

I am assigned a bunk atop a gruffly bearded black twenty-year-old called Weezy. Most of the time, we sleep. As Weezy tells me, “any time asleep is free time. You sleep away your bid, you golden.” There’s a lethargic, even leisurely air in the dorms. Weezy tells stories to the cube about messing with the COs, like the time he dipped toilet paper in coffee grounds and left it by the COs’ door because it looked just like a turd. It’s the same sort of insouciance and shit talk that you might find at summer camp, the derelict element of boys being boys.

When the stories end, the conversation always shifts back to the perpetual question: Who’s the best rapper in the world? The new jacks front Tech N9ne, Gucci Mane, Drizzy, Chief Keef, while the OGs come with Eric B. and Rakim, Biggie & Tupac. Peanut, who bunks next to Weezy and me, doesn’t care who you talking about, because for him it’s J. Cole or nothing.

“Come on, ‘Born Sinner’! It don’t get smoother than that! You made me versatile, well-rounded like cursive, know you chose me for a purpose, I put my soul in these verses. Oooh lord he didn’t just do it like that, did he?”

Peanut is a big man, pushing 300 pounds yet is surprisingly nimble, and the memory of J. Cole has him bouncing on his lower bunk with a grin that lights up the dorm. He has a $200,000 cash bond so will likely move to the blocks when they open up. He has a solid alibi and pretty much knows the real guilty party, but when I ask why he hasn’t told the prosecutor, he looks at me like I’m crazy.

“Snitch, bro, you serious? Ain’t no snitch bitch, better believe that. I’m a hold my mud.”

So the memory of the sweet sounds of J. Cole in the HCC dorms it is. In the evening, the conversation turns more nostalgic, reminiscent about love or food, the first meal that might be eaten when one’s bid was done. Lavish detail is paid to the conjuration of red snapper, butterfish, ackee, steaming okra, cooking out on an early summer evening, Red Stripes under the moonlight listening to reggae. Peanut would eat southern fried chicken, collard greens, buttermilk biscuits with his mother’s gravy, an entire watermelon.

“How about that pizza place in New Haven, Frank Pepe’s?” I venture.

“Ever been there?”

“Shit, Professor has been all up and down this state, ain’t that right?”

I nod and quip but don’t tell them that I’ve been not just up and down the state but around the globe. I keep them, from some impulse of self-preservation and understanding of my own immense privilege relative to them. If all goes according to plan, I will be in Hong Kong teaching my graduate students in a few weeks. As a matter of fact, as an Asian-American, I am part of the most successful demographic group in America (though even that monolithic notion lumps together communities like Cambodian-, Laotian-, Bangladeshi-, Nepalese- and Burmese-Americans who fall well below the median household income of all Americans), and there’s no question that the racialization and policing of our communities has been vastly different than of African-Americans. In the past, Asian immigrants have been excluded from gaining entry into the U.S. and becoming citizens, have even lost their personal property and been sent to internment camps like Japanese-Americans were during World War II, but that’s vastly different from the history of segregation, police brutality, and systematic discrimination that African-Americans have endured for centuries.

I’m not Black, but I’m a man of color. For the officer who arrested me, dark skin was dark skin, but for the readers of the Hartford Courant, the misdemeanor offenses of a South Asian professor were simply scandalous. “Put him back on the first dhow to India so he can rejoin his fellow slum dogs,” opined a particularly insightful commentator. Instead, I put myself back into the knockoff black leather wingtip oxfords my father, Appa, would wear each morning to work. I can imagine better what it might have been like for him in the early 1970s. He was a first-generation Indian immigrant who arrived in America with only his latent pride and dreams of grandeur, and instead of luxury, he found himself a poor engineering student at Howard University, barely scraping by and dependent upon his relations for meals and company. Washington, DC, back then (and even now, to be fair) was far from anyone’s idea of a utopian paradise, but Appa was there on campus during that historical moment when over a thousand students occupied the administration building of Howard University with a set of demands, some of which, like the establishment of an Afro-American curriculum, were eventually granted.

What I wouldn’t give to be able to borrow his eyes when, just over a month later, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and Trinidad-born Black activist Stokely Carmichael touched off the riots that left nearly half of DC burned to the ground and entire neighborhoods within blocks of the White House looted. Amma has told me how Appa had to scurry home under cover of night to hide when President Johnson ordered the army and National Guard to erect machine gun emplacements around the federal buildings.

It boggles my mind to imagine my serious, orthodox father sprinting down the same streets that Black Panthers patrolled in green field jackets, binoculars around their neck and assault rifles upon their shoulders, while looters carried off transistor radios, televisions, and appliances and soldiers in fatigues shot tear gas into the streets. He came from India to find the American dream and instead found that dream deferred and then literally exploded outward into the civil rights movement. How might that experience have colored his relationship to this new country and shaped his children, as yet unborn?

Instead, I simply imagine the first place I would dine after a month of eating chicken slop, mystery sausage, elbow macaroni slathered in unsalted sauce, and the fish patty that constitutes the “vegetarian” meal option. I have lost weight, for sure, and I’m always hungry. Breakfast is served before 6 AM, lunch at 10:30, and dinner at 4 PM, so that by the time evening rec time rolls around, everyone is ravenous, trying not to think about how long it would be until breakfast. Jailhouse cooking is as inventive as a challenge on Top Chef. The men steal whatever they can from the chow hall, pieces of bread or fruit to make pruno—a kind of bootleg liquor— else meatballs, peanut butter, boiled vegetables, and ground hamburger meat, so that in the evening they can cook up a dazzling array of dishes.

The most common is mofongo, Puerto Rican soul food, but made without mashed plantain mixed with chicharrónes. Instead potato chips and crackers are crushed into powder and mixed with water to make a fine paste. The water is squeezed out of it and spread in an opened garbage bag folded over the mixture, rolled flat with a cylindrical deodorant container. Meanwhile your cell-mate mixes up soups, rices, mackerel, chopped sausages, Mrs. Dash seasoning, cheesy beans, and whatever else is floating around to spread on top of the chip paste, cover with the top of the bag, and twist into an enormous sausage that can be sliced to accommodate your whole cube. If you’re feeling bold, you can even make a stinger, a convection oven made from a cardboard box, some garbage bags, salt water, an extension cord being held open by a broken piece of a nail clipper to retain the charge. The mofongo bag will shrivel as it cooks in the salt water.

I put forth to the crew that when I get out, I would like to have nothing more than some paper-thin masala dosa and an entire South Indian thali, rice, sambar, rasam, kootu, vadas, curd, crispy papads, some salt lassi to wash it all down. I’m explaining the properties of the perfect dosa, crispy and light yet supportive of its filling, when I’m interrupted.

“Yo, you got roti there right?” asks Gerald, who has asked me on many occasions about all things Indian. And so the conversation swings to Buss Up Shut Chicken and Potato Curry Roti and the steel drums of the West Indian day parade and what Gerald wouldn’t do to be sitting out on his stoop with his girl. He’s the daddy to her three kids—none of them even

his—and she loves him so deeply for it.

When he mentions his children, I think of my own daughters, 7 and 3 now, precocious creatures whom I haven’t spoken to in weeks. Though I had been dead set against it, my then-wife Parker insisted, and so we made the decision to tell the older one where I would be for six weeks. I framed it as a kind of teachable moment, explaining that even if we didn’t agree with the rules, we had to follow them, and if we didn’t, there would always be repercussions. I would be totally safe, I assured her, unsure myself of the truth of what I was claiming. Outwardly I smile when Gerald shows me the photographs of his own three curly-headed cuties, none of whom resemble him, in complexion or body type.

Since 1980, the incarcerated population in the United States has increased from around 250,000 to over 2.5 million, an upsurge of nearly 1,000%. I recall reading that there are more black men in prison, on probation, or on parole than there were slaves during the Civil War, and looking around, the racial dimension of mass incarceration is incontestable. The vast majority of inmates are black or Hispanic—Puerto Rican, Dominican, Mexican, Haitian. There’s someone from Iran, who won’t speak to anyone, and only a handful of white guys, probably six or seven in this dorm of 60 and at least two of them are rumored to have serious weapons charges pending. I’m the only one who originated from India and in all likelihood one of the few who had the advantages of a middle-class suburban home, access to higher education, and a retirement plan.

Otherwise it’s all brown and black men, including a very strange lad with large, mournful eyes who swears he’s from Bohemia. He has been incarcerated for obscenity and public indecency, having purportedly been seen handling himself in a public library. I don’t push for details. He provides us a vision of Bohemia instead, the place he claims to be from, somewhere I have apparently mistaken for a kingdom that became the Czech Republic, because he assures me it is actually an unknown island in the Caribbean. It’s a place without electricity or modern commerce; you disembark and immediately enter the realm through two stone gates and it’s as if you have rediscovered the Garden of Eden. There is alligator pear, pop poi, and blim blim growing wild and a marketplace totally based on the barter system. Later I would hear that he might have flashed a child and that is why everyone is so hard on him.

At morning rec time, we are awakened to the television tuned to some ungodly talk show and the sounds of men flapping bath slippers down to go wash up or shave. By then the card and chess games have started, except in the poker cube that doesn’t get going until much later. I go out to play basketball in the yard guarded by barbed wire.