During the peak of summer’s intense heat, I spent time with the work of Amy Sara Carroll. Next to my fan and open window, I assembled these poems and watched them blow around my desk. I was captivated by how they participated in their own creation and how each image or information byte constantly required me to think about them in their broader political and environmental context. Carroll is the author of Secession (Hyperbole Books, 2012), Frannie + Freddie/The Sentimentality of Post-9-11 Pornography chosen by Claudia Rankine for the 2012 Poets Out Loud Prize (Fordham University Press, 2013), REMEX: Toward an Art History of the NAFTA Era (University of Texas Press, 2017), and co-author of [ ( { } ) ] The Desert Survival Series/La serie de sobrevivencia del desierto (Office of Net Assessment/University of Michigan Digital Environmental Cluster Publishing Series, 2014). She is a member of the Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0, which coproduced the Transborder Immigrant Tool, and she

participated in Mexico City’s alternative arts space SOMA. Carroll has been a fellow at Cornell University’s Society for the Humanities and the University of Texas at Austin’s Latino Research Initiative. Currently, she is an Associate Professor of Literature & Writing at the University of California, San Diego. This interview exchange took place over email.

Monica Rico (MR): Hi Amy, I want to thank you for talking to me about. your work. As a poet, scholar, and visual artist, how do you begin your process of creation? Does it start with an image, a line, or since this selection of work is politically motivated, does it begin with watching/reading the news? Where or how do you receive inspiration?

Amy Sara Carroll (ASC): To begin, many thanks, Monica, for your engagement with my work and for this dialogue in the guise of an interview about my practice. In answer to your first three questions: all of the above, although I don’t know if I would go so far as to use the word “inspiration.” Lines, images, single words, events linger. Sometimes I cannot write; sometimes, I cannot not write (granted, writing can also serve as a cocoon).

As I respond to your questions, California’s wildfires rage. In early September, Lesbos’s largest refugee camp Moria — which I reference in the activation instructions that accompany “Lesbos” — burned to the ground. In the first 2020 presidential debate, Trump instructed the “Proud Boys” to “stand back and stand by” (before the moniker “Proud Boys” was playfully and urgently repurposed in the Twittersphere). Covid-19 and national and planetary pre-existing conditions persist. Paling in comparison — meaning, never on par with forced migration — there’s the cleaving effect of my own recent re/location/s. For over a decade, I lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan. August 2017, I returned to Ithaca, New York (where I’d completed my MFA two decades before). August 2018, I moved to Austin, Texas. August 2019, I moved to New York City. August 2020, I moved to San Diego, California. My practice reflects the places I’ve called “home” — even if that noun, frequently recalculated in the last few years, approximates something closer to a transitive verb for my fourteen-year-old son and me.

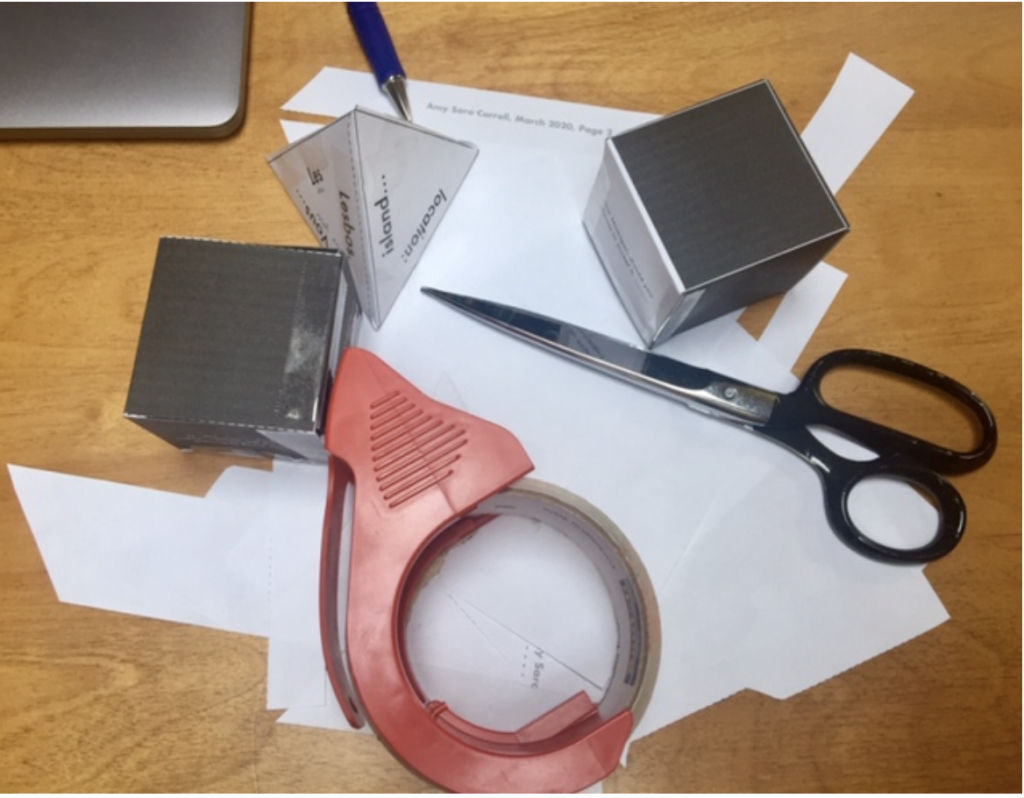

MR: I don’t want to tell people to destroy this new issue of the Michigan Quarterly Review, but they should definitely consider ripping these pages out and making the cube and triangle that accompany the two “Activation Instructions” poems. I had so much fun cutting, folding, and tapping the sections together. I like how, in doing so, it got me to narrow down my focus and become a participant in the art. Also, they are light enough to be flipped by the air of a fan! I let them blow around on my desk for a while, and I loved it when “Manhattan: Weapons of mass construction. ‘No More White Presidents!’ Verb” came up. Or, I know they are not meant to be read together, but the triangle and the cube created “location: island… / ly. We _________. Radio, / active: ‘When will the Island / belong to Bruce Lee?’” How important is the element of playfulness (including surprise) in your work?

ASC: The image you send of your assembled copies of my poems made my day. Reconfiguring the book-object, the materiality of language, the reading pacts we make with authors whose work we cherish are formal concerns — but hardly constraints — that have consistently animated my practice. Recent conversations in poetry about the varied futures — or lack thereof — of the “performative,” the “documentary,” and the “conceptual” have re/invigorated my writing (even if sometimes I find myself disagreeing with positions taken), including these poems and their “activation instructions.”

When I pair these conversations with preceding or contemporaneous, sometimes cross-referential, conversations in the visual arts, I’m reminded that the keyword trio has been and can be wielded to name social dramas of disenfranchisement, deadening bureaucratic documentation, and Conceptual -isms that doggedly delimit how we define sentience. The stakes of these conversations exceed the formal. The keywords in question speak to what cannot be computed by governmentality; they stand-in for “surprise” (your parenthetical), the countenance of “Something rogue. Something else that you have to figure in before you can figure it out,” to fall back on the language of Toni Morrison. I recognize the value of (poetic) play as reparative, as social justice and action, as critique, survival, resistance, as an anti-gravitational force in the multi-verse.

My current work, from which this series is taken, serves as one response in progress and process to two sets of chronic questions I’ve found myself asking (the exact language of the questions and the boundaries of the two sets continues to elude me): 1) (How, when) might we destroy books to rewrite them? How, when do / could we enable processes of destruction to double or return to us as radical revision, repair, reconstruction? 2) How, when, and in what ways could / do poems activate their readers, generate unanticipated networks of relation? Could we / I “build” poems that literalize, maximize such processes of activation, participation, community?

In a prior collection, I played extensively with erasure, grayscale, strikethrough. Currently, I’m more interested in inviting the reader to join me in performing dimensionality. If we take the leap of faith of reorganizing a journal’s issue simply by removing one of its pages, following a set of activation instructions, and creating an independent, free-standing “poem,” what might or could we imagine for the world at large?

By all means, tear a page out of MQR’s Fall 2020 issue; to reorder something is not necessarily to destroy it. A week ago, I received my MQR contributors’ copies. Although the verso and recto of “Michigan-Manhattan” do not align perfectly, although the designer inexplicably could not imagine rendering the pair in landscape to enlarge the size of the four haiku’s fonts on the exterior of the cube, it’s still possible to assemble a poem-object for yourself (see pages 653-658 of the issue).

PS: In NYC, as I drafted these poems and packed boxes for my California move, triangles and cubes proliferated on our apartment’s windowsills. My partner wondered if they multiplied in the moonlight as we slept. Attached, a photo of one assemblage to serve as a companion to your image of fan-swept 3-D poems. A shout out to other readers: please send images of your versions of these assembled poems!

MR: When you say it like this, it makes me extremely curious about my initial hesitation in destroying a page. I wasn’t sure if I was “allowed” until I said to myself, “obviously, she is asking me to do this.” I love how I was invited to create something tangible, to “activate” myself as part of the art and emerge from the shadow of an imagined reader.

ASC: Monica, you are reminding me that activation is multi-directional! Your response to my work pushed me to reformulate how I was thinking about these poems, too, e.g., I didn’t think to send an image of the boxes on my windowsill until I opened the photograph you’d sent. Then, I realized it might be interesting or useful to offer you another window — so to speak — on how these poems function in my larger built environment. Shortly, I’ll return to how publishing these poems is reshaping them; how yours and others’ engagements with the work are actively influencing my writing of it. But, before that happens, I’d like to honor this project’s initial influences (and to go so far as to use the word “inspiration” preceding your wraparound final question) because no project — like no life in motion — arises or sustains itself in a vacuum.

Let me put this another way. I might be mixing metaphors in what follows; but I’ve always found writerly prohibitions along such lines themselves to function metaphorically (per the logic of Hortense Spillers insights on “ungrammatical bodies”). The thinker-tinker-filmmaker-visual-artist Cauleen Smith has an amazing pocket book — small enough to slip into a pocketbook — called Human 3.0 Reading List 2015-2016, an offshoot of a gallery and web-based project she exhibited with a similar name. Smith begins the book’s concluding manifesto in all caps: “BLACK PEOPLE ARE AT WAR WITHOUT THE PROPER ARMOR. WE REQUIRE INOCULATIONS THAT REPEL THE SEDUCTIONS OF CORPORATE SERVITUDE.” She goes on to describe her project — a series of portraits of books covers — as all she was “able to draw right now,” as an incomplete vaccine against a bevy of -isms and -phobias. The proposed remedy? Smith, like Antigone, encourages us to consider sharing the labor.

I loved Human 3.0 Reading List 2015-2016 pre-COVID; returning to it recently (I bought a physical copy to keep at my desk), I am lightning-struck by Smith’s uncanny prescience. Sooner versus later, I plan to sit down and begin sketching my contributions to the project. My plan: begin with Smith’s book, then focus on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (and The Dream of the Audience: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982)), Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Cecilia Vicuña’s QUIPOem, Bhanu Kapil’s Schizophrene, Hugo García Manríquez’s A-H Anti-Humboldt, Hsia Yu’s Pink Noise (submerged in an aquarium as she “performed” the volume), Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta’s catalog Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, Cristina Rivera Garza’s Los muertos indóciles: Necroescrituras y desapropiación, Adrian Piper’s A Synthesis of Intuitions, Tlacolulokos’s El Sur Nunca Muere, Susan Briante’s Defacing the Monument to think along clear lines of sustenance.

Staying with my 3D poems, I’d add two monographs that helped me to rethink my relationship to performance, writing, and artmaking by way of the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica’s work: Irene V. Small’s Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame and Laura Harris’s Experiments in Exile: C.L.R. James, Hélio Oiticica, and the Aesthetic Sociality of Blackness. As Smith writes, “Bless our hearts. / Read. Write. Resist. Yes.”

What would you add to Smith’s collection?

MR: This is wonderful, and I love Smith’s notion of “weaponizing our minds.” The books I would add to this already stellar list are: Three Tragedies: Blood Wedding, Yerma, Bernarda Alba by Federico Garcia Lorca, Autopsy of an Engine: and Other Stories from the Cadillac Plant by Lolita Hernandez, Ana Castillo’s Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women Of Color edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, The Living Great Lakes by Jerry Dennis, Paloma Negra/Black Dove (forthcoming from FlowerSong Press) by Leslie Contreras Schwartz, Nikki Giovanni’s My House, Racism 101, and Gemini: An Extended Autobiographical Statement On My First Twenty-Five Years of Being a Black Poet.

Speaking of influence, I was excited to read your ekphrastic poem “Activation Instructions (viii)” that takes some inspiration from Tony Rosenthal’s Painted Corten Steel cubes. I don’t know how many times I’ve walked past the Cube and given it a push. I did not impel a pole through the center of the cubes I made, but I did spin them around between my thumb and forefinger. I enjoy this poem because it is a catalyst for memory in the speaker, specifically the mother’s memory of her son as a small child. It feels like a return to when life felt normal before the pandemic. How has living in isolation changed your work, and how has it changed how you work?

ASC: For the past six months, I have been living (and relocating) in very close quarters with my partner and son. This has and has not felt like isolation. Concretely speaking, in an 800-900 square foot apartment, I’ve been hard-pressed to carve out time-space in which to be alone, let alone write. Comparing notes with family, friends, and colleagues, I recognize that my situation is hardly unique even as we’re conscious that concerns about the latter mark our “pandemic privilege.”

When COVID-19 cases were first detected in the United States, I was living in New York City. As The New School, where I worked, and my son’s middle school, transitioned to virtual learning platforms, we socially distanced from others who couldn’t afford to do the same. My partner joined us in the city. We watched spring arrive outside our apartment’s windows, venturing forth only for essentials. I wrote “Michigan-Manhattan”’s activation instructions in late March 2020 when I contemplated this “new normal” of restricted movement. The parallel universes of the Astor Place and Regents’ Plaza cubes function as the central axis or conceit around which the poem’s instructions and recollections spin. We — my son and I — took comfort in the synchronicity of Tony Rosenthal’s installations in Manhattan and Michigan, in the memory of where we’d been and where we were. That NYC time of reflection feels far away now, almost as far away as the period in Ann Arbor that the poem details.

Of the latter, I’d note, while friends and family did their best to support me at the University of Michigan, I cannot forget the mind-numbing loneliness-fatigue I felt in my (final) Ann Arbor years. I seek to make peace with the contradictions that animated my life/work in that period in the activation instructions. In particular, moments with my son in “An Árbol” and with Michigan colleagues and friends will always eclipse the medical and professional grief, the heartache I experienced. During COVID, however, rememories show up on my doorstep, prove hard to outpace as I witness so many trying to hold onto their health, homes, and jobs. All to say, the before and after implied by your question isn’t so clear cut for me.

Still, the early months of the pandemic feel far away, too, for reasons that have nothing to do with my cross-country move. Following George Floyd’s murder by the police, following the wrongful deaths of countless black and brown people, like many post-Memorial Day, I had the visceral sensation that sheltering in place was no longer an option. The experience of donning masks and gloves and joining others in New York City’s streets continues to stand in stark contrast to the experience of PAUSE, Governor Cuomo’s stay-at-home mandate. Circling back to your question: I cannot answer how what I’m describing has changed or is changing my work and work process. Not yet, at least. Such dramatic shifts in the everyday, precipitated by myriad forms of longstanding structural violence, are for better or worse, ongoing. What I know for sure: 2020, for me, will never be about optimizing my work productivity. I want to participate in some small way in a larger collective effort to ensure that we — a far-ranging “we” — live in a world in which survival’s amply imaginable and imagined.

MR: Navigating change is something art is always trying to understand or at least comment on.In your second poem, “Activation Instructions (vii),” the visual language is a mirror to the directions it is giving. The first three lines are a manual, including the later use of “ASSEMBLE” and “TAPE or GLUE.” The slashes imitate the water’s waves before the poem even gets to the island of Lesbos. Then the poem flips from an instructional mode and begins to center on the immigrant/refugee crisis, which is a theme throughout your pieces. How did you become interested in working with and in this polarizing topic?

ASC: Regarding my pairing of 3-D poems and their activation instructions and recalling our prior exchange about this work’s provisional, processual qualities: When I began to compose three-dimensional poems, I imagined it would be obvious to readers that the poems should or could be cut out and assembled. Friends and colleagues with whom I shared poems suggested otherwise, noting that most people — contrary to my expectations — would not register that they had “permission” to dismantle a bound book or journal (hear the echo of your own experience of the work). I submitted one of these poems to the Boston Review. At some point in my interactions with one of the journal’s editors, I asked if I could add a simple set of “activation instructions” to the poem. He responded enthusiastically to the idea. I envisioned these instructions as quasi-spoof on those supplied by conceptual artists like Sol LeWitt (think Wall Drawing 273’s execution instructions). In this vein, what I offered was minimal. That said, no matter how hard I tried to pare down my addendum, I could not adhere to a formulaic “LeWitticism.” Instead, I found myself renewing my efforts to approach the poem — its materiality – as a vehicle for thinking about relationality. In this spirit, ever since, I’ve tailored each set of “activation instructions” to match the 3-D poem it accompanies, making clear that the poem and instructions function as a complete package. “Lesbos” — which spoofs on an 18th-century poem by Voltaire often used in beginning French classes to illustrate the difference between a formal and informal address to “you” — trebles three languages: French, Spanish, English. Like many of the early 3-D poems I wrote, it can be broken down into a haiku and its title. But I wondered after writing it, “Does the brevity of the text risk obfuscating its subject matter – the un/natural disasters of planetary displacement and dispossession?”

One day, I realized that I could include in my activation instructions, not only assemblage directions (which you correctly note are included in all caps and are scattered throughout the poem), but also information about the poem’s focus, e.g., in the case of “Lesbos,” the so-called Mediterranean migrant crisis (yes, the waves are choppy). This special issue of MQR addresses, challenges, and grapples with persecution. Human displacement cannot be separated from a host of other pressing planetary concerns: Climate change, specters of eco-catastrophe, extreme weather events already upon us are producing climate refugees as natural resources like clean air and water are threatened, dwindle, disappear. Such unnatural crises exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities. Reactions to migrants reflect longstanding (environmental) racism, xenophobia. Women and children are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. I could continue; you could amend and expand the argument I’m de facto forwarding here regarding interconnection. What I want to say: immigration can only be isolated as a “topic of interest” in the theoretical. When and if immigration produces polarizing debates, it does so because an attention to the un/documented movement of human beings obfuscates much lengthier conflicts over resources that have circumscribed and continue to limit our understandings of what it means to be human or otherwise. One educated guess: De-obfuscation, or at the very least translucification, remains a best practice, a set of best practices, here and now, then and there. (Note: transparency at this political juncture feels like a vexed noun and concept to recuperate.)

MR: In staying with the poems, they feel as if they are a continuation of your previous work on the U.S.-Mexican border. I am thinking specifically about “my LAR,” where we can see the actual division of the United States and Mexico with black and blue lines on the silver fabric. This separation has been made even more pressing since the Supreme Court ruled the construction of the border wall was not unlawful. “my LAR” is a collaboration with your mother. She is a South Texas artist, which leads me to believe that you have a familial connection to the Texas border. But you are not just focusing on the visual of the border; you are also summoning Gloria Anzaldúa’s “third country.” From Borderlands, Anzaldúa writes: “Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.” How does the U.S-Mexico border speak to you, given your participation in the collaborative project, the Transborder Immigrant Tool?

ASC: You could read my contributions to this issue as a continuation of my prior work. “my LAR,” for examples, is in conversation with my previous efforts, passions, preoccupations insofar as all of my work is about Mexican-US borders (I did intentionally write “borders” in the plural), about the Mexican-US subcontinent. I grew up in South Texas but spent my earliest years and many childhood summers in Mexico (Mexico City and Xalapa, Veracruz). My coming of age overlapped with Greater Mexico’s NAFTAfication. (Note: Ironically, I had to leave Texas to be introduced to Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. I often tell students that after first reading Borderlands/La Frontera, I read it again and again, then I carried it with me everywhere I went. Borderlands/La Frontera and Toni Morrison’s Beloved made it possible for me to keep on keeping on in my undergraduate years.) I had not thought of it this way, but I suppose in the best of all worlds, “my LAR” might serve as a kind of textual “security blanket,” too.

At the very least, it cannot be separated from the Transborder Immigrant Tool for an altogether different reason: For several years, I have been co-writing a play about TBT’s development and past and future forms of distribution, which honestly troubles even the definition of the project that you offer above. In reality, the work-in-progress I reference isn’t only about TBT anymore. It touches on myriad topics from evolving US immigration policy and debates to the parameters of what constitutes border art or post/conceptual art and writing. We thought we’d written the book to closure, then the 2016 US presidential election transpired. We’ve been revising the play ever since. We were slated to present one of its acts in Mexico City’s Centro de Cultura Digital, not once but twice. The first time we had to cancel for personal (medical) reasons, Covid-19 scrabbled the production’s premiere the second time. In the meantime, as we prepared to push the cross-genre text off the page and onto the stage, I found myself day-dreaming “activated props” for it. For years, I’ve held in my mind’s eye Joseph Beuys 1974 infamous performance or “social sculpture,” I Like America and America Likes Me wherein he’s locked in a gallery with a coyote and a few miscellaneous, but now iconic objects — a hat, felt blanket (Beuys viewed felt, the fabric itself, as therapeutic), cane, and several copies of the New York Times. In the performance, Beuys drapes the blanket over his shoulders. As the Trump administration revised, intensified separation and detention policies for US asylum seekers, images of refugees, many of them children, huddling under mylar blankets, were put into wide circulation. I wondered, “Could a mylar blanket be repurposed to offer psychic as well as physical warmth?” Then one day, I saw the word “mylar” differently, its split syllables reconfigured as two words approximating connection-protection, a reference — possessive — to a “lar” or (Roman) household deity revered to protect hearth and home. I picked up the phone and called my mother, Donna Senf Carroll. What emerged out of our conversation doubles as a kinship diagram of Greater Mexico, geography divided but contiguous. What resulted functions in sync with but also independently of the aforementioned play I’m co-authoring.

MR: What I find most engaging about “my LAR” is how it is a collaboration with your mother and that it “separates syllables, not families.” It comments on how this current administration has a complete disregard and continues to criminalize and dehumanize immigrant/refugee families at the border. With this work, you offer me a point of light—a place where a mother and daughter can physically be together and create art. This project’s base is a quilt, which to my understanding, is an assemblage of pieces that makes a whole and not just any whole, but a blanket—a thing that protects us and keeps us warm. It is entirely unlike the texture of a mylar blanket, which, at best, is only a flimsy thing. What was it like to work on this project with your mother? Was this something you had done before?

ASC: Yes, this project is a quilt. It has and does not have the texture of mylar because its materials include not only a literal foil mylar blanket (which, in keeping with the spirit of TBT we purchased online for a few dollars), but also felt and cotton fabric. My mother hit upon this combination because we quickly learned mylar tears easily when you try to sew or stitch something onto it. She consequently pieced the other fabrics onto the mylar by hand (a difficult and time-consuming process), first giving the blanket a backing or a “base” to address mylar’s “flimsiness,” as you say. Together my mother and I laid out the quilt’s composition and made choices about the text-image placement — its “infrastructure.” For example, I saw the words “my LAR” over a map of Greater Mexico. To make it absolutely clear that the design referenced a geography, my mother suggested we add the two flags to the design. I wanted the blanket to be landscape versus portrait-oriented to best represent the sheer length of the border. The mylar blanket’s unwieldy prefabricated dimensions at 54 x 84 square inches were certainly more than sufficient for that purpose. My mother wanted to mark differences in border biomes — water versus land crossings. I could go on about the design choices we made. What seems most important to emphasize is that we aspired to create a tangible object — one that might serve, forgive the pun, as a small foil to the ubiquitous image of the mylar blanket now indelibly associated with migrant detention centers in the Trump era. What we didn’t fully compute until we began the project: mylar is highly reflective.

Although we considered using gold, pink, or green mylar blankets, we appreciated that in the silver, especially it is impossible not to catch blurred sight of yourself. Prior to “my LAR,” mother and I had never made a quilt together — she is an experienced quilter, though. She has helped me “compose” other poems — sand-sculpting words at Padre Island National Seashore or firing and glazing a clay poem I hand-built. While “my LAR” loosely references Beuys’s piece, we both imagined more clearly bringing to this prop’s foreground echoes of radical textile traditions, including the work of the Gee’s Bend Quilters Collective and the AIDS Quilt, which also double as maps and kinship diagrams. Additionally, Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolé capes and Cauleen Smith’s In the Wake protest banners came into play for me with “my LAR.” I rarely give my mother books as gifts, but after reading Julia Bryan-Wilson’s Fray: Art + Textile Politics, I immediately bought her a copy of the book. Which is to say, Fray found its way into this project, too.

MR: Thank you so much for this interview and for naming the artists/art that has influenced you, but I’d like to know what is inspiring you now? Who or what is giving you life?

ASC: My relocation to the Tijuana-San Diego corridor. Demonstrators and demonstrations for social — and specifically racial — justice across the United States and the planet. BLACK LIVES MATTER.