Why I Chose It: Michigan Quarterly Review Reader Bryan Byrdlong introduces Kathryn Nuernberger’s “Ode to Maria Barbosa” from our Fall 2020 Issue.

In “Ode to Maria Barbosa” the titular Maria appears almost as a collage, framed by multiple women from different eras (including the author herself). The author draws deftly from award winning Brazilian historian Laura de Mello e Souza’s detailed account of Maria’s persecution at the hands of the men and institutions that accused her of witchcraft, turning their accusations from sources of condemnation to sources of empowerment.

This process succeeds partially because of how the author leans into the idea of rumor, a main one being “that Maria Barbosa could use her magic to invoke a sea devil.” Here the essay distinguishes itself as an ‘ode’ choosing to celebrate Maria and her would-be powers. The author makes the suggestion that, “you could make a woman like Maria Barbosa seem insignificant by dismissing love spells as something superficial…but reading these court records, I wonder if “love spell” isn’t sometimes what a person says when they can’t say “cancel” or “call out,”” conjuring a frame of political resistance. As she goes on, the heroine is given more influence by association. By the time the author has wondered, “Maybe Maria Barbosa “destroyed man men” in the manner of Josepha, putting water she had used to wash her legs into her master’s food.” it would not be undue to see even in the perceived witchcraft a revolutionary act.

The myths, the maybes, seem almost an invocation of Mnemosyne as the author delves into the collective memory surrounding Maria while also employing it as a muse. At a street protest the author connects the sign with a “Sharpied line from Dolores Huerta: “Walk the street with us into history.,” to the “descriptions of “spells that appeared in the trial records—how a person might be given a piece of paper with some symbols written on it, to keep in a pocket”. Here the connection of the disruption of witchcraft to the disruptive nature of protest tactics becomes clear, Nuernberger’s juxtaposition of Maria’s story with her own what allows the individual at the heart of the story to truly be seen in a new light. By the end I couldn’t help but admire Maria as a “warrior” even as I can only laud this reimaging of the ode as, itself, magical.

Ode to Maria Barbosa

Laura de Mello e Souza, the Brazilian historian I’ve been reading, wants to demonstrate how history is more than the stories of great men and their “discoveries.” If, she says, you read carefully enough through court records, ship manifests, and archeological evidence in trash heaps, “it becomes possible to make out faces in the crowd, to extend the historical concept of ‘individual’ in the direction of lower classes.” When my friend arrives, running late, her sign flapping awkwardly in the wind, I dog-ear this page and drop the book in my bag, so we can join the rally together.

The rumor, according to Souza, was that Maria Barbosa could use her magic to invoke a sea devil. When she was exiled to Angola after the first accusations of witchcraft were levied against her, she accurately predicted the future for the governor and was set free. The second time, as in the first, she was accused of having “destroyed many men.” The specifics of her alleged love spells are not itemized in the existent records of her trial, but maybe like Marcelina Maria, who was similarly accused, she cooked an egg, slept with it between her legs, then fed it to the man she wanted. Or maybe like Isabel Maria de Oliveira, whose confession survives though she did not, she put perfumed roots in her intended’s clothes and chewed alcaçuz roots to fill him with passion. Or like Florencia de Bomsucesso she took curvōes to the crossroads and threw them there while invoking the spirits to bring him to her door. Maybe, like these women’s, hers was a magic designed to affirm the dignity and beauty of their bodies and their lives against colonial authorities who insisted otherwise.

On the way from the Bahia region of colonial Brazil to Lisbon where Maria Barbosa would stand trial for witchcraft before the central authorities, the ship was overrun by pirates. The men were all killed; she was taken as captive. “Captive” means that most likely she was raped repeatedly before being dumped on a beach in Gibraltar.

I suppose you could make a woman like Maria Barbosa seem insignificant by dismissing love spells as something superficial and slight that girls play with at sleepovers, but reading these court records, I wonder if “love spell” isn’t sometimes what a person says when they can’t say “cancel” or “call out,” “direct political action” or “overthrow.” During the Inquisitorial Visitations of the late 1500s, the official charge was to locate and punish those practicing Judaism in the Brazilian colonies, but trial records indicate the judges were not opposed to supplementing that role with assistance in the policing of free African, Afro-Brazilian, and indigenous people and otherwise bolstering the social control mechanisms that safeguarded slavery and colonial rule. The inquisitors would happily write the bureaucratic reports necessary to justify the brutal torture and execution of an enslaved person thought to have bewitched a master. They would gladly make an example of any African or indigenous person demonstrating or rumored to hold power.

Maybe Maria Barbosa “destroyed many men” in the manner of Josepha, putting water she had used to wash between her legs into her master’s food. Or like Joana, put a piece of cipo picāo root under her tongue when she had to talk to her mistress in order to protect herself. Maybe she was there when Antonia Luiza called together black and brown women to “adore dances” to seek the ancestors’ help in dominating the masters’ wills. Perhaps like the enslaved people in Minas, she took scrapings from the soles of a master’s shoes to prevent beatings.

The plan for the march had been to end in front of the locked doors to city hall, where someone with a bullhorn would try out a few of those familiar chants that never seem to catch on. I expected it would unfold as marches often do—a herd of us shuffling and squeezed onto a narrow sidewalk through downtown. At each intersection some of us would go ahead, while others held back, until we became a clump and trickle the passing traffic could easily ignore. I tend to think at such protests about how often parading people through the streets has been used as a form of punishment. But instead, from the middle of the crowd, came the call that anyone among us who had rallied just a year earlier in the nearby suburb of Ferguson now knew well: “Out of the sidewalks into the streets.” And the response: “Out of the sidewalks into the streets.”

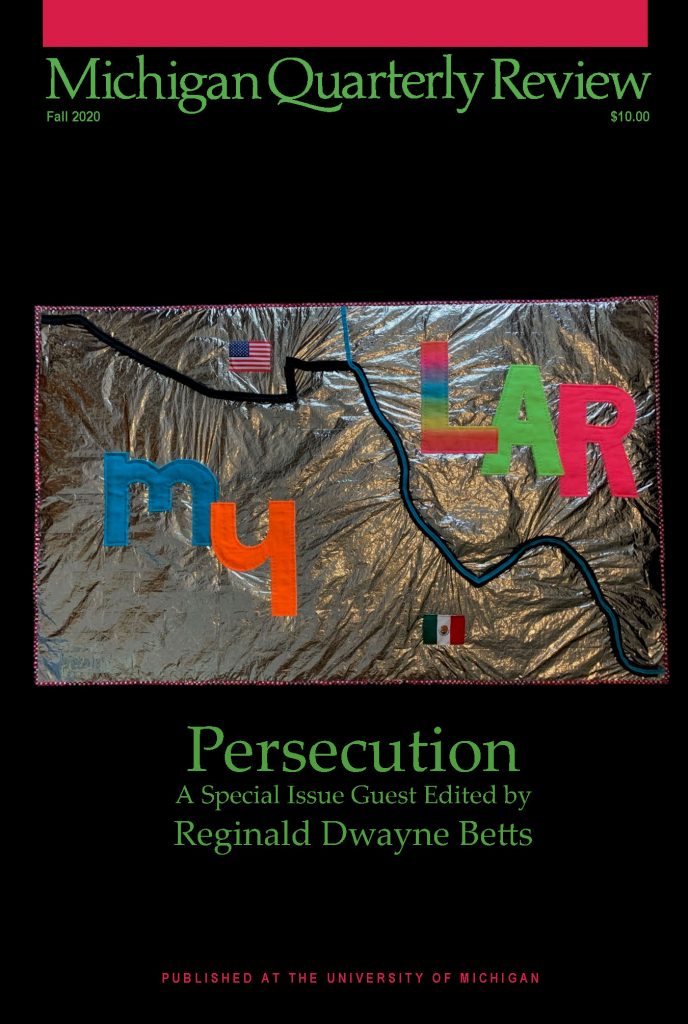

Some members of our group made barricades of themselves, stopping traffic. Others remained on the sidewalk, bearing witness as the wail of sirens grew louder. I could tell you of the shouts and the tears, the man in the Camry trying to push people aside with his vehicle, the worry on the faces of the women who had planned and publicized a peaceful protest against family separations at the border, the resolve on the faces of the people in the street ready to go to jail for this cause too. I could tell you how I have struggled with where my body, my privilege, my solidarity, and my voice belong, but mine is not the face in the crowd I want to linger on here. Instead I want to offer you an ode.

An ode because it is the form for victory, to be recited after a great chariot race or on national holidays in praise of warriors. Because it is the form wherein a speaker tries to imagine a right relationship to power. A right relationship because if such a relationship already existed, there would be no need for the ode. An ode because I want Maria Barbosa to be the warrior celebrated by the poets in the square, her victory the kind we are asked at the festivals to imagine. I want to hear her story mapped along this ancient form that begins in the present, then reaches back to a mythical past full of tantalizing digressions before landing on a couplet, punchy and memorable, with the rhythm of heartbeat, that moves the power it received from the state that commissioned such a verse into the will of the gathered crowd.

When the sirens reached the intersection, we dispersed into the city, no longer sure who among the passersby had been with us. Here and there I saw some people with posters rolled under their arms or tucked in a bag or pressed in a hurry into the recycling bin. I thought about the descriptions of spells that appeared in the trial records—how a person might be given a piece of paper with some symbols written on it, to keep in a pocket or at the bottom of a shoe as a charm or protection or hex. One sign had a Sharpied line from Dolores Huerta: “Walk the street with us into history. Get off the sidewalk.” And another from bell hooks: “The practice of love offers no place of safety. We risk loss, hurt, pain.” Cornel West was there: “Justice is what love looks like in public.”

Picking herself up on the shore of Portugal, Maria Barbosa decided to walk across the country straight into her own trial. I know her choices were limited, and she had no good way to hide, but nevertheless, our mythic hero decided to walk into the courtroom instead of being dragged there against her will. And when she arrived, she requested of the tribunal a cloak to cover her ragged nakedness after such a terrible journey. She demanded it. Because, she told the men in a clear voice, she was not the woman they imagined her to be.

Maria Barbosa knew those men wouldn’t give her a cloak.

That wasn’t why she asked for it.