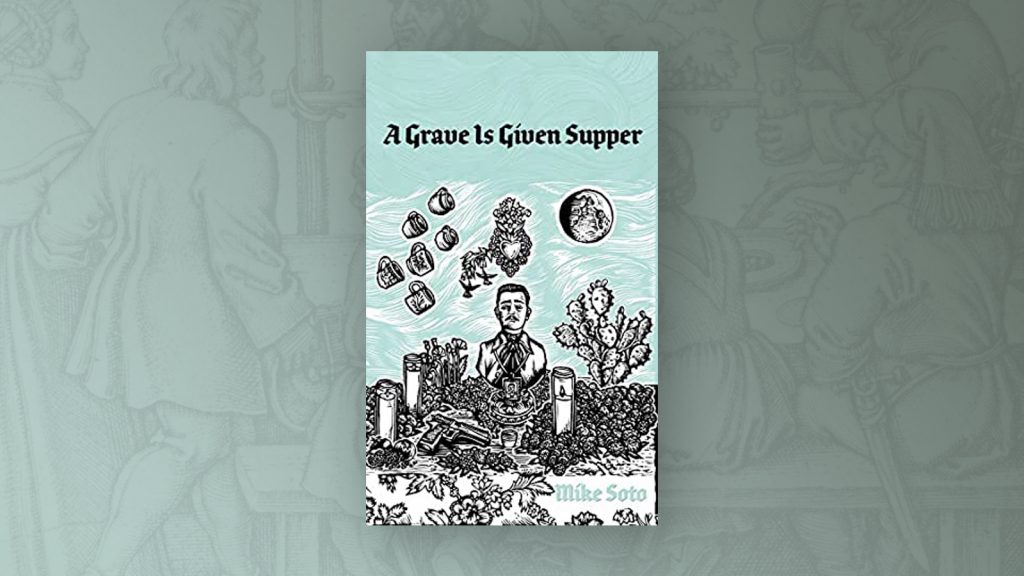

Mike Soto’s inaugural collection, A Grave is a Given Supper, is forceful and varied, shedding unflinching light on the intricate paths of two protagonists, Topito and Consuelo. These two dynamic speakers find themselves embroiled in the ‘glitter and grit’ of El Sumidero, an imagined US-Mexico border town ravaged by the drug war. Throughout the collection, Soto employs dark imagery, invocations of narco-saints, and folk spirituality to ultimately obscure the certainty of destiny, especially in a world with various forces vying for the opportunity to play God. The opening poem of A Grave is a Given Supper, “Blank Chapel, or Consuelo’s Mistake,” interrogates this liminal rift between sanctity and criminality — holy and heist, as Consuelo searches for escape in the confines of a vandalized cathedral: But seeing the vandalized walls, a message started then smeared, the mad steering of a hand thru paint—to Consuelo the ruined whitewash was blindness smeared into sight. A rage she shouldn’t have recognized, the one house of God she shouldn’t have rushed into. Seemingly inspired by the vandalism, Consuelo finds refuge by adding her artful touches to the defaced walls: “nothing to stop her from / getting closer, tasting, first with her finger, // the glimmer in the grit.” What Consuelo is thus able to create in this moment of rapture feels like worship, a kind of worship free from the strictures of dogma or the watchful eyes of congregants. In this manner, Consuelo uncovers the sacred on her terms—her unique “glimmer” amid spatial and societal “grit.” In like manner, throughout the collection, Soto dives into the landscape and underworld of El Sumidero ready to expose the moments of glimmer that don’t happen despite, but rather in tandem with, a gritty world. For example, when Soto first introduces the collection’s second main speaker, Topito, we find him alone in the scorched desert outside El Sumidero after having buried a “picture” of his mother alongside his “first toy.” Though his age isn’t specified, these details emphasize Topito’s youth. A youth symbolically stunted by the burial of these childhood relics. Topito’s sudden thrust into adulthood is further underscored by the fact that in the same scene, he parts with his father: [I] said goodbye to my father who left determined to get across the wall commonly known as the brow of God. After that, the horizon I gazed at for a grip on what do now, next, for the rest of my life, gave me nothing. All I could do was sit, duck my head into the darkness. The border wall between the United States and Mexico is repeatedly deified throughout the collection. Nevertheless, border wall mythos isn’t always aggrandizing. For Soto, the “brow of God” is also penetrable, and even amorphous at times. While individuals, like Topito’s father and others, try their luck at sneaking beyond this godlike threshold, Soto introduces another force that is continually at odds with, and at times overcomes God’s brow — El Sumidero’s networks of organized crime. Soto sets the scene for El Sumidero’s crime world bluntly, “In the beginning there was murder, & out / of murder shadows & barking ran up / to read cipher on walls, cold-blooded // creates plotted their revenge behind smoke.” The incantatory heft of “In the beginning” echoes the biblical creation story. In this vein, Soto displays the might and carnage of El Sumidero’s criminal actors while tactfully gracing a level of humanity to those both complicit in and victims of criminal activity. Eventually, both Consuelo and Topito find their lives so overrun by El Sumidero’s vices that they must participate in it to survive. It is in these ostensibly incriminating moments that Soto renders the gamut of each speaker’s intricate ethical compass. Soto uses the motif of Malverde’s shrine to illustrate this breadth of humanity. Narco-saint Malverde, otherwise known as Jesús Juarez Mazo, is a legendary folk hero of Mexico’s Sinaloa region: a bandit lauded for stealing exclusively from the rich to bless the poor. In a modern context, he is most notably recognized as the patron saint of Mexico’s drug traffickers. Throughout the collection, the Shrine of Malverde attracts throngs of faithful pilgrims, while also functioning as an omen for violence and murder. For example, in “Untitled (Tunnel with Horse & Rider),” Topito encounters Malverde at a gravesite, “the stones that first made / his grave. Above them, a cornucopia / slept around the vague bust of Malverde.” Additionally, in “Breaking an Open Window,” Topito again encounters Malverde’s bust while trying to elude a stalking murderer, “Death…the hired gun / who follow me: a stranger whose stare / is careful.” Nevertheless, in the final poem, when faced again with the possibility of death Topito, cries out fervently to Saint Malverde with this prayer “lit immediately” on his lips: Malverde, tú que moras en la gloria y estás muy cerca de Dios, concédeme este pequeño favor: llena mi alma de gozo, dame reposo, dame bienestar, y en los espacios más oscuros, hazme dichoso. Thus, Soto’s invocation of Malverde highlights the power of crime in birthing syncretic religious belief, a cultural phenomenon known as narcocultura. In addition to Malverde, Soto also utilizes Mexican-American folk saint Santa Muerte, the saint of death, to signify moments of danger and devotion. For instance, in the lyrically gutting “The Dead Women,” Santa Muerte is invoked after a long elegy commemorating the multiple mournings women often endure in the face of rampant violence. Ultimately, within this pantheon of narcocultura, Soto pushes the limits of faith and reveals how belief can coerce individuals into transgression, while also highlighting the human impulse to seek the divine in moments of weakness. I find this tension, this ethical knife-edge of faith and vice to be one of the collection’s most successful interrogations. At tension exemplified by these lines from “Topito’s Yes,” it took us to the altar with the Virgin Mary seated next to Santa Muerte— arranged as if not caring who sees them at the same table. Equally irreverent and sacred, these lines and the piece as a whole force the audience to appreciate the confluence of seemingly disparate patterns of belief, asserting, in part, that no single deity controls the given supper of humanity’s graves.