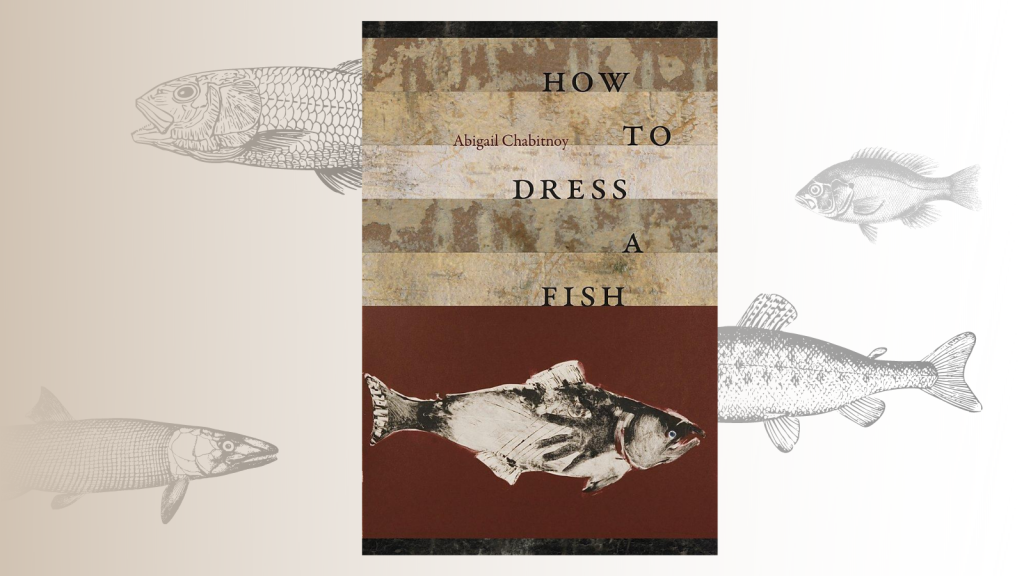

Abigail Chabitnoy very kindly sat down with me at the Poets House in Tribeca on a clear July morning to talk about her work. She had read from her debut collection How To Dress A Fish (Wesleyan University Press, 2018) the previous evening as part of Poets House’s Showcase Reading Series. The collection, which was shortlisted for the 2020 Griffin Poetry Prize, is a reflection on her native Alutiiq heritage; her great-grandfather, Michael, was sent from Kodiak Island, Alaska, to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where founder Richard Pratt’s motto was “Kill the Indian in him, save the man.” The layers of America’s genocide and forced assimilation, including the Carlisle School, where modernist poet Marianne Moore taught for three years, are still widely unacknowledged. Abigail approaches these layers from within her own family history. Her collection is polyphonic; family voices, reflective voices, and mythological voices move her poems towards continuous questions. Poet Sherwin Bitsui has called the collection “essential and captivating,” and Joan Naviyuk Kane writes, “poems like these change the world.”

Stephanie Papa (SP): Your great-grandfather, an Alutiiq native, was sent from Kodiak Island, Alaska, to Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, an experience central to your collection How To Dress A Fish. However, the landscape and/or mindscape of the Aleutian Islands, your family’s ancestral homeland, figures more prominently than Pennsylvania, where you grew up.

Abigail Chabitnoy (AC): Yes, a lot of this was imagining work, and a lot of it was from research. I had done some archival work in Anchorage in college, so some it came from even the first time I set foot in Alaska. It was so far from Kodiak but still closer than I had ever been before, so that place had a physical impression on me. Other images came from ethnographic narrative accounts of how water plays a role in place and history. It wasn’t until I got to Woody Island, though, that I felt the visceral connection I was expecting. Although Kodiak was on my great-grandfather’s records, most of the documents just have recordings of births, baptisms, and marriages, not necessarily where people lived or died. We don’t know where his siblings were buried or anything. But we do know he was on Woody Island.

SP: So, your great-grandfather may have been exposed to these assimilation strategies, Christianity and the English language, before he was taken to Carlisle?

AC: Yes. That was one of the hardest parts of the research, trying to come to terms with the reality of his personal experience and how little evidence there was in the archival data. On the one hand, there are true horror stories of Carlisle—it was not a pleasant experience, to put it mildly—but then you have these pockets of students who did alright by certain Western criteria, who went off to college, even if their college experience wasn’t great because of the expectations placed on them. Or you have a figure like Jim Thorpe, who was this great American athlete on the one hand, but was stripped of all his medals as a result of these internal politics, which were nothing he was prepared to navigate while at Carlisle.

SP: Right, he even had one of his shoes stolen right before the Olympic event.

Yes, so you had this figure that was tragic in many ways, but one who also, while at the school, was held up as a great athlete and shining example. We only have a few records and letters of my great-grandfather, but we know he was a baseball player, and that he was coming from a place that was already colonized by the Russians. Even in the town of Kodiak, there was a lot of anti-Native sentiment for a long time. When the Americans took over, anyone who could claim Russian ancestry did, because it was perceived as better than identifying as Native in terms of how the government treated them. Michael already had Western clothes, and he came to Carlisle with a Western family name. He was probably speaking English already and most likely Russian at the time. And he had only recently already lost his parents and siblings. So many of these experiences that were so traumatic for many students had basically already made their way through Kodiak. Carlisle might not have been as jarring of a scenario for him. So, on the one hand, there is outrage, because Carlisle was truly terrible in its ambitions, but for my great-grandfather, an orphan who played baseball, maybe it wasn’t as bad. Maybe it was. We simply don’t know. His voice wasn’t preserved in the archives. The athletes had different quarters, different diets–they were treated better because they were the face of the school. So, it’s difficult to try and reconcile that possibility.

SP: What I feel is the most engaging aspect of your poetry is the complex architecture of it: your play with sound, homonyms, aposiopesis—unfinished phrases—and the intricacy that forms this map.

AC: At the end of the day, that’s what I want the most out of this book. I don’t want this to be a cultural critique, or to garner attention as a poet only because the background seems exotic. I want the work to stand for the work. I do believe that it’s important to have an understanding of the context, but returning to the poetry is more important, to approach it like other poetry texts. It’s a matter of being willing to listen too, to other interpretations. One of the larger problems in academia and how voices and narratives are given authority is a tradition of not acknowledging cultural knowledge that doesn’t fall neatly and clearly under the umbrella of a Western framework. Western academics will announce, “Hey, we proved your theory,” and marginalized people are like, “We didn’t need you to prove anything, it didn’t change our knowledge of the world just because you didn’t believe us.” It’s a very Western thing to try and pinpoint things into neat boxes and not to accept that it’s messier than that, and I think one of poetry’s greatest strengths as a form is how it can draw attention to that messiness.

SP: Absolutely, your poetry seems to give us access to different rooms. All the doors are kept open, where we hear simultaneous narratives—Michael, Carlisle records, the shark, the sea. One of these streams in your collection is the mythical, lyrical narrative; Pyrrha on Mount Parnassus or a fox shapeshifting into a woman.

AC: The fox poem is actually an erasure of a traditional Alutiiq folk tale. It took me two years to find this book, a collection of Alutiiq folktales. You can, for the most part, easily find collections of other Native American folktales, and there are lots of crossovers, but most are very different from Alaska Native stories. The worldview is different, the cosmology, the landscape. I wanted to find a way to integrate these stories. This whole project largely started because I wanted to engage with myth, with surreal approaches, different ways of imagining reality. I loved folktales, which is what drew me to study anthropology in undergrad. Then in grad school, I was reading about Navajo stories and motifs, and I found them so interesting from an aesthetic standpoint. Still, it didn’t feel right to put them in a poem, as I’m not Navajo, and don’t—can’t—fully understand the ramifications of some of these figures to those people living today. These stories are taken very seriously, and there is a lot of guarded knowledge still within cultures. At that moment, I knew I had to go back to my own culture and find our stories. The fox story was one of the first ones I had read, and it brought me back to the incomplete narrative, or the way these stories get bastardized from their original telling and watered down for a broader audience, a common scholarly approach. It can be useful, but you have to ask how much is lost in doing that. I was interested in mimicking this erasure, but also in turning it on its head. The erased story took on more meaning for me. It became a story I could fit myself into.

SP: Is this where the “I” comes into your poems?

AC: Yes, hollowing out a place for myself in the story. It’s similar, in a way, to writing about Carlisle; I had to ignore certain things to be able to continue the story. I couldn’t dwell so long on the fact that maybe my great-grandfather liked Carlisle. We don’t have evidence to support that either.

All I know is that Carlisle was the rupture point for learning about our culture, because that’s what brought him to Pennsylvania, it’s what separated us from our tribal community. Who knows what kind of relationships we would have had if he didn’t stay in PA. I can’t quantify all the things I’ve lost, or deny the privileges I’ve been born into, but I have to ask, what if he had gone back?

SP: Your collection is charged with those questions—who gets to keep records, and what is left out in our family histories, oral or written? The answer is often a colonial interference; those who were entitled to keep the records were white people, often assimilating or essentializing native histories.

AC: My great-grandfather died right before my grandfather was born, and no one talked about Michael for a while. No stories were passed down. As one cousin said, “no one talked about the Indian anymore.” Traditional Native families can often have this beautiful extension of familial relations across generations, but I didn’t grow up having my grandparents telling me stories. I know that my grandfather’s brother looked more Native, and growing up in Hershey, PA, he bore more of the brunt of being Native, whereas my grandfather had curly red hair, taking more after his mom. But they were both called “half-breeds.” They both suffered from being cut off from their paternal heritage. So there were no stories about Michael. Maybe he didn’t want to go back to Alaska because there was trauma in losing his family there. Another problem with going back might have been that everything these students had learned in school wasn’t accessible or didn’t reflect the reality in their communities back home. These stories weren’t captured in the archives. They didn’t serve the mission of Carlisle.

SP: The speaker also questions the lack of a female voice in the family story. Throughout the collection, women come in and out of stories and dreams, but in your poem “As Far As Records Go,” you write, “The women in this story never had a chance, did they, Michael?”

AC: The men organize the genealogical records, and who they married, what their occupations were. A woman in a workshop once said to me, you’re talking about these men, but where are the women in the story? And I just don’t have access to them, but they have to be there. I feel they’re there, but I don’t have a direct way to tell their story. Sometimes the absence of recorded female stories is a cultural one; anthropologists and photographers recorded stories from the men because culturally, the men weren’t going to let the women be secluded with these strangers they didn’t know. And not in a controlling way, but simply thinking about the time period, if you have a foreign guy coming into the community, the more vocal man might be the first person to talk to, in terms of the rationality of the time. It’s not that they weren’t telling stories, or that women weren’t also storykeepers. But again, their voices didn’t make it into the officially preserved records.

SP: I can feel that absence in your fragmented architecture: there are gaps in the bricklaying, crossed out words, “a moth-eaten hole” in memory. Words also seem mobile. In your poem “Family History,” letters gradually disappear. How did you decide to flesh this out on the page?

AC: I didn’t have a strict process. I was interested in different approaches to documents in poems and historical processes, overlapping narratives, and how erasure is represented. The smaller-font lines especially do feel very much like a different voice coming in, almost as an echo. They are lines that aren’t done with me yet; they’re still in this narrative, and I felt them expanding beyond the scope of the poem and conversing across.

SP: Yes, it seems that the “I” in your poems is not necessarily a singular speaker, but a polyphonic echo.

AC: I can’t speak for any of the people in the book, even for some of them who we do have records of. But these line breaks helped to find ways of making my own voice multiple, trying to figure out how to bring in other perspectives and possible narratives, not my singular mouthpiece, but a sense of community and build that community in my poetry. I want to leave it open; that’s what I love about poetry, that language can open up the possibility for more, and not reduce meaning to less.

SP: You also infuse English with Alutiiq words and phrases. How does this switch come about for you?

AC: I’ve taken one semester of Alutiiq, but I was often limited to the sentences that already exist on online resources. The Alutiiq Museum has a great “Word of the Week” series. An elder uses the featured word in a sentence, and there is a paragraph or two about the word. So, when I wanted to use the language, I’d look at these micro-essays. For example, I might feel that the poem needs some further richness, and I’ll think about the images already there—let’s say wind is a predominant image already. So, I’d look up the word for wind, and sometimes in the essay, other images or stories would arise that seem unrelated on the surface. It could be talking about hunting, how hunters use the wind to dry out skins, for example. If I hadn’t gone to that specific entry, I wouldn’t have made a connection. But in this way, I did start to see the poems and the language as bridges between experiences.

Alutiiq has the same setbacks that other indigenous languages have. Historically, the Russians certainly committed atrocities against the Alutiiq people, but their approach to conquering was less driven by a “we have to make you look and sound like us” mindset. They completely disrupted subsistence lifestyle by forcing the Alutiiq to hunt for otter furs, a commodity that Russia profited from, but they didn’t care so much about what language people were speaking in the home. In fact, Russian Orthodox priests actually helped the Natives write their language and maintain it.

The current revitalization of the Alutiiq language was largely funded by compensation from the Exxon-Valdez oil spill. The settlements from the disaster provided the money to open the Alutiiq Museum. Regular access and practice of the language can continue to evolve with technology to keep it relevant. New words are created so that people can speak without having to break into another language.

SP: If the non-Alutiiq reader has looked up the words in your poetry, they’ll see that sometimes the Alutiiq phrases are directly translated in the following line, but not every time.

AC: When you read Ezra Pound’s Cantos, you’ve got these clusters of languages, and the assumption is that you are either “educated enough” to know those languages, or you have access to translate them. Of course, now, with the internet, we have much more access to translate. But when you have this colonial overlay, this question of access is even more pronounced; when you give a text to a student who doesn’t have the same education as you had, and you say, “You don’t understand this language? Why not?” there are historical prejudices rooted in that expectation. So it is a question of access, as well as a question of mimicking—how much do I want to provide that access? All of the words in the collection are searchable because I myself had to take them from the online library; my own access was limited. So, if you’re willing to look up the languages in the Cantos, why not be willing to look up Alutiiq online? Sometimes the phrase is enough, and I want there to be a gap, the unknown meaning. Other times the meaning is so important that I want to give the English translation, but I don’t want to make it easy for you. I want to preserve access, but point out the inequality of access, just like anything else.

SP: The novelist Tommy Orange has expressed his frustration with identity becoming internalized, and then performative by nature. I wonder if you’ve experienced this.

AC: I remember, before my collection was published, I went to see the movie Neither Wolf Nor Dog. The film centers on the idea of how to tell the story, how it gets perceived, especially that romanticizing notion. Around the same time, there were several news reports of Native writers who had been claiming indigenous identity, but no Native entities claimed them back, so there was public pushback; they didn’t have any credentials or paperwork, which is a problematic requirement in itself. It’s the only cultural situation where you have to prove your identity by presenting your degree of blood. But it’s because there remains a temptation and opportunity to exploit; these writers were deliberately misrepresenting themselves because they knew that “Nativeness” sold in certain circles.

Meanwhile, I had this book that I was writing, grounded in my indigeneity, but I grew up in central PA passing as white, with little understanding of what it meant to be Alutiiq. Before this project, my only experience with my culture was the research I did to write scholarship essays for college. At times, it did feel like I was being called on to be performative in ways I questioned. I worried about misrepresenting my culture and tradition in seeking to be a sincere participant. It took a lot of talking to mentors, and my family, asking them how they felt about the work, about complexities of identity and belonging, to overcome what sometimes felt like imposter syndrome. I had to sit with my motives, interrogate those motives just as I was interrogating historical records in the book itself. It was important for me to remain grounded in my own family history and my own experiences. The book touches on Alutiiq history because having learned that history, I can’t ignore it. It’s my history too. It shapes my understanding and experience of the world. But I’m not trying to pretend I grew up on Kodiak, fishing for my dinner, fighting for recognition.

I accept that some people are not going to accept where I belong or who I am. There are over 500 recognized Native Nations in the United States, with different histories, cultures, and beliefs—you can’t expect them all to have the same view on every issue. I grew up removed from a large part of who I am, where I’ve come from–through the actions and by design of those who would erase that history. It’s not a common experience, perhaps, but it’s also not uncommon. So, my voice can reach this audience, and that’s another reason to continue doing this work, to push back against a narrative of erasure, of lessening.

SP: What is inspiring your work now?

AC: My next project is looking at the stories we tell ourselves to survive—in terms of violence against the landscape, women, indigenous people—and looking for the patterns, for underlying connections, at how stories shape our understanding and worldview and then trying to envision something hopeful out of it. That is, I’m trying to write with an awareness of the current barrage of crises–political, social, climatological–and the gravity of the situation without giving in to a defeatist mentality. It’s hard to write some days because you think, what is a poem going to do? But I can’t not write, so I have to imagine a way forward. In my poetry, I look less towards convincing others who already adamantly disagree with me on these issues, and instead think about the next generation, how to open them up to thinking differently.