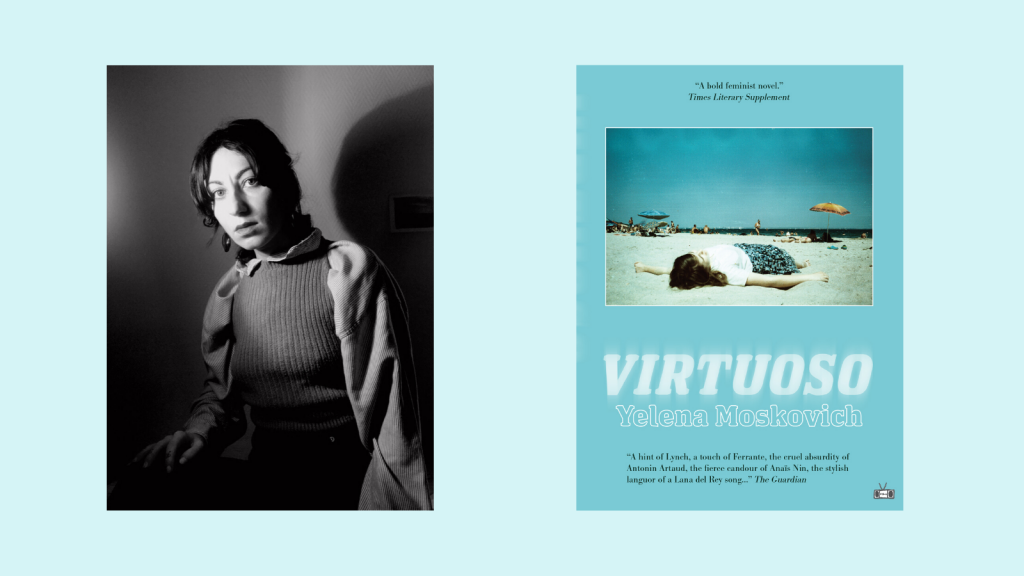

Yelena Moskovich is the author of two novels: Virtuoso (Two Dollar Radio, 2020) and The Natashas (Dzanc Books, 2018). Born in Ukraine (former USSR), Moskovich emigrated to Wisconsin with her family as Jewish refugees in 1991, and now lives in Paris. She studied theatre at Emerson College in Boston, and at the Lecoq School of Physical Theatre and Université Paris 8 in France. Her plays and performances have been produced in the US, Canada, France, and Sweden. She has also written for Vogue, The Paris Review, Times Literary Supplement, Mixte Magazine, and Dyke_on Magazine. Moskovich has won the 2017 Galley Beggar Press Short Story Prize in 2017 and was a curator for the 2018 Los Angeles Queer Biennial.

In her recently released novel, Virtuoso, Moskovich tells a surreal and kaleidoscopic tale that spins us through communist Prague, post-Soviet America, and Paris. At the core of the novel are Jana and Zorka, two resilient young women who grow up together exploring each other’s bodies as they explore their place in an ever-fracturing world. Inserted throughout the book are the stories of other women who seek connection and acceptance—in chatrooms, lesbian bars, hotel suites—and are willing to risk their safety and their lives to find one another. Virtuoso is a novel / is a performance / is a dance with movements and variations / is poetry / is film / is a palette splattered with colors / is a body out of breath. Virtuoso is truly a sensual euphoria, one that must be experienced firsthand.

In the interview below, MQR Online spoke with Moskovich about her writing of Virtuoso, rebellion, women in love, the fundamental surrealism of human existence, and more.

CF: What was the first seedling of Virtuoso? What inspired you to start writing it?

YM: I have a sort of amnesia about the creative origins of a work as soon as I finish it – so I’m afraid I have no seedlings to report. But perhaps it was Zorka and her eyebrows. “Zorka, she had eyebrows like her name.” That line I wrote early on told me everything I needed to know about Zorka and her path.

CF: While the majority of the novel focuses on the complicated friendship and romance of Zorka and Jana, the reader is privy to several storylines featuring other female couples and love affairs, such as Aimée and Dominique, Tiff and Deandra, Dominxxika_N39 and 0_hotgirlAmy_0. Did you always know the book would include and intertwine these additional threads, or did their significance to Zorka and Jana’s plot grow over time?

YM: I’m not someone who does a lot of planning or structuring ahead of time. In fact, I do barely any. The body of the work grows as a discovery. The various character veins feel like an organic part of this body, no matter how small their presence seems to be. Aimée/Dominique and Amy/Dominika are indeed a sort of doppelganger couple, each in their own dimension. But I didn’t decide ahead of time to construct this parallel. It came up from the writing, like a wildflower I didn’t plant. Same with Tiff and Deandra. I could have spent so much more time with them, it was hard to leave these two. But it felt like they came out of the weave-work and spoke and then left when they were done speaking.

I am constantly being interrupted by my characters, major and minor. I believe in the benevolence of interruptions. It is my way of communing with something beyond me, to let myself be thrown off my intended path, to be thrown off knowing. It’s a sort of disappointment, I’m literally being disappointed from my place of knowing. For me, in art as in life, I am very curious about the creative power of these metaphorical and literal disappointments.

CF: Were any of the threads especially easy or difficult to write? Are there certain characters in the novel that have inherited traits or elements from you?

YM: On the one hand, I can say that there is absolutely nothing in this novel that is autobiographical. That’s part of why I love (and write) fiction. I don’t want any obligation to have to “be me” or represent myself. I am often drawn to the symbolic or fantastical plane because I feel I have the most freedom of expression there. I’ve never felt fully at ease with realistic or naturalistic writing, because the literal plane is very startling to my character, to who I am. I need a place of nonsense as well as a place of sense; a place where non-language (image, sensuality) can be primordial to the text; a place of secrets that have forgotten who they are being kept from; a melancholia without analysis; a protest against intellectualization; an intuitive craftsmanship.

The idea of ‘ease’ and ‘difficulty’ is often evoked in relation to the artist, as a sort of value of their genius. Sometimes difficulty is glorified – the struggle, the suffering. Sometimes ease is glorified – the wunderkind. But I think the true difficulty is when you feel like you are going against yourself. For the most part, I rarely feel or suspect that I am going against myself. In that way, I feel very much at ease most of the time, because I am not adding any additional layers of struggle, doubt, or difficulty to an endeavor that already – naturally – contains these things as part of the process.

CF: You were born in Ukraine, emigrated to Wisconsin, and now live in Paris. How do these landscapes from your past and present influence what you write about and the form in which you write?

YM: My writing often takes place in multiple cities or circles around characters who are a product of a sort of imposed movement, and who are likewise grasping at their own agency in the extension of this movement.

There is a specific trauma to flight. Literal flight in terms of immigration and the more metaphorical flight – the flight from oneself.

Trauma hides itself in our depths, and to seek to encounter it is also to seek to encounter our depths. In this way, my interest in the trauma of flight and the trajectories of encounters with our depths shapes my storytelling into this “non-traditional” novel form – as it has been labeled.

My prose is fertile in elemental contradictions (air/earth, water/fire) as well as the bending and twisting of time (past, present, future). I am not just trying to tell the story that I want to tell, in this case, a story that touches on themes of immigration, post-Soviet diaspora, and queer identity in the midst of huge global and national structural changes—I’m also trying to evoke the substance of these things, a visceral experience of both flight and deep communion, through the form of the story itself.

CF: As much of the novel takes place in communist Prague in the 1980s, Virtuoso seems to be exploring the differences and dangers of conformity versus rebellion. In a communist world, conformity equals survival. But as history shows, rebellions have often created the foundations for progress, equality, and freedom. At one point, Zorka’s mother pleads to her free-spirited and unruly daughter, “Please, don’t be weird.” But are conformity and rebellion total opposites? Is there conformity in rebellion; can one be a rebel follower? How has your relationship to conformity and rebellion changed throughout your life, or even as you worked on this novel?

YM: Both conformity and rebellion are natural cycles in the formation of an identity, individual and institutional. I’m not so much trying to look down on or glorify either state or experience. We need a certain level of conformity to create communities and a sense of tribal connection, so to speak. But we also need rebellion to put ourselves into question and to check in with who we are and with the systems in which we move, to make sure that they are serving our most dignified humane self.

I hope that in my writing, as in my life, there is a curiosity and fluidity between these two states of being. I love this line from Lao Tzu “The living are soft and yielding / the dead are rigid and stiff.” To me, the texture of ideology is just as important as its profession. There is so much life in softness, flexibility, yielding. And there is so much death in rigidity and stiffness.

CF: Can I just say that the liberal and direct language you use to write about women’s bodies and women’s sexual pleasure is so refreshing and, um, pretty hot? Was there a certain turning point in your writing career when you realized that you didn’t have to (or want to) shy away from writing plainly and truthfully about women’s bodies, and specifically queer women’s bodies?

YM: Thank you! It’s always been a fascination of mine, actually, how text carries female desire. I remember early on, when I was barely a teenager, I discovered the way that male authors wrote about the female body with this merciless swagger. I envied the language they had at their disposal and their confidence. At first, I mimicked, I wrote in straight-male-drag. But little by little, I began to find my own language and confidence, one that did not have to be like theirs.

Now, I don’t feel like I have to be in relation to that language at all. I am neither trying to mimic or subvert it. I’m just doing my own thing, as I need to do it, and learning as I go about what feels true and genuine to me about translating the body onto the page.

CF: Throughout Virtuoso, the reader is witness to a number of strange and surreal scenarios. Aimee believes she is being stalked by “the color blue.” A gang of street children grab and breathe into grown adults’ genitals. A young American girl logs into a lesbian IM chatroom and begins a virtual relationship with an Eastern European housewife whose husband has literally chained her to their house. What draws you to writing about the surreal, the disturbed, the bending of logic and the laws of physics?

YM: It’s still so strange to me that ‘realism’ is at the epicenter of fiction. Reality, as the literary canon has provided, is a number of points of view on our experience. But our human experience is also fundamentally surreal, meaning multi-faceted. We dream, we fantasize, we hope, we self-talk, we fear, we project…etc. every day. This is our real phenomenology. Historically, we have privileged one of these points of views. And by ‘we’ I mean certainly not a we that me or people like me were included in.

The fluidity I try to express in my point of view, including mysticism, symbolism, and sensuality alongside the logical or ‘real’ dimension, is just my way of showing up. Sometimes people see it in stylistic terms, but my world is not a style. It may be a style to others who do not experience the world as I do, but it is not a style to me.

CF: In your acknowledgements, you dedicate “a kindred bow to all those who subvert with a big heart, together, incognito, our cosmic song, our lyrical transgressions.” Can you tell us about a few artists you admire who have made their way in the world by subverting social norms and expectations?

YM: When I wrote that, I was actually thinking of something a bit more quotidian, almost banal, not necessarily linked to big artistic acts of transgression – thus the word ‘incognito’ – but their transgression is in quietness, in the substance of their gestures, in the tonality of their voice, in the human warmth that they share.

There are, of course, artists I admire for their subversive tenderness, but I prefer to leave that space in my acknowledgements as a universal, anonymous, quiet space; not for those specifically in the spotlight.

CF: Tell me more about this cosmic song. What is your next verse?

YM: Ha, I’m touched that little line in the acknowledgments piqued your interest so much! Our cosmic song, as we have it now, is very much off-key. But there is also beauty and meaning in discord. My current contribution is mainly to listen. My next verse is one I give from my open ears.