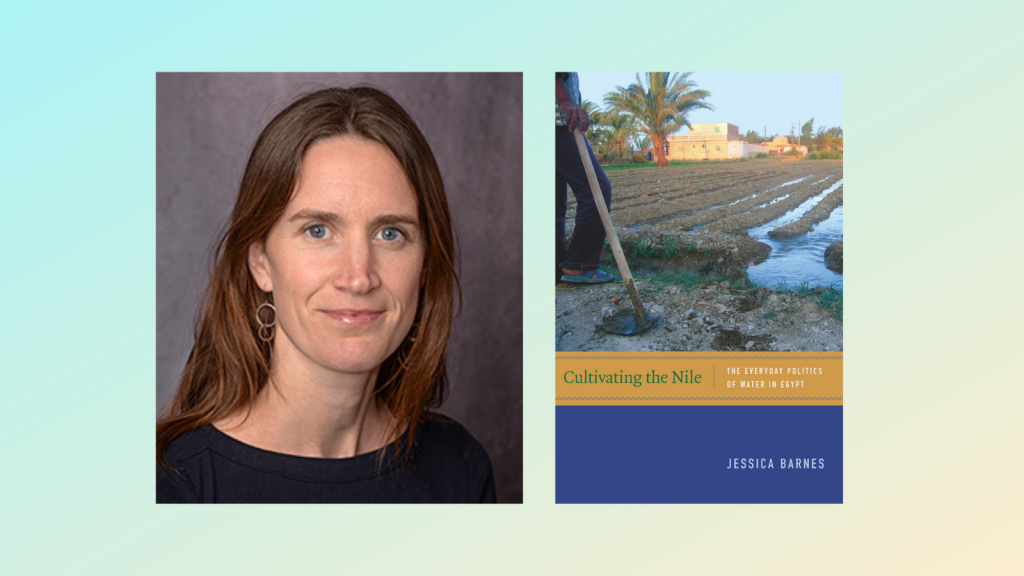

Dr. Jessica Barnes received her Ph.D. in sustainable development from Columbia University in 2010 and held a postdoctoral fellowship with the Yale Climate & Energy Institute and Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies from 2011 to 2013. Dr. Barnes’s research examines the culture and politics of resource use and environmental change in the Middle East. Her first book, Cultivating the Nile: The Everyday Politics of Water in Egypt (Duke University Press, 2014) is an ethnographic study of water and the politics surrounding its use. In subsequent work, she has explored the intersections of climate change, water, and agriculture, focusing in particular on how scientific understandings of climate change and its impact on the water resources of the Nile Basin are produced, interpreted, and negotiated in different knowledge communities. Related to this research interest, Dr. Barnes has co-edited a collection of anthropological essays on climate change with Michael Dove, entitled Climate Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives on Climate Change (Yale University Press, 2015). Dr. Barnes is currently working on a book titled, Precarious Staples: Wheat, Bread, and the Taste of Security in Egypt, which examines the longstanding and widespread identification of food security in Egypt with self-sufficiency in wheat and bread.

Natalie Lyijynen is a freshman at the University of Michigan double majoring in the Environment and Biology, Health, and Society. She’s passionate about the science behind sustainability and plans to pursue environmental law. In addition, she’s always loved the arts and has further realized her love for creative writing after being a part of the Lloyd Scholars Program for Writing and the Arts. Through the Undergraduate Research Program, she joined Michigan Quarterly Review to help research the global water crisis and solicit for their Spring 2020 issue. Realizing the value of interdisciplinary scholarship in communicating about environmental issues and with the help of the Michigan Quarterly Review, she conducted an interview project. She interviewed five professionals who bridge the gap between the sciences and arts in order to shed light on the barriers faced in work on climate and water issues. Her purpose was to address historical precedents, research how stereotypes have changed or persisted, explore the professional impact of the interviewee’s work on climate and water issues, and gain insight on global trends and what the future may look like for interdisciplinary scholarship.

Natalie Lyijynen (NL): Humans have always expressed their relationship with nature through culture and art and writing, such as Stonehenge or Gobekli Tepe. “Interdisciplinary work” isn’t new. Culture has been connected to food, the environment, resource use, and local politics. We have communicated as communities and shared our knowledge through them. However, I definitely think that it’s different professionally today. There are different stereotypes and barriers, with increasing concern over climate change and increased political divides. In the context of climate change and its deniers–what work do you believe artists and social scientists have in front of them?

Jessica Barnes (JB): You started by saying that there was a break from the past. That there’s always been this relationship between nature and culture and that you think it’s very different today. My starting thought is that I’m always wary of talks of break with the past. I feel that there are many more continuities than there are big steps. In some ways, climate change inspires creativity. There are a lot of different creative endeavors around the environment, and I don’t think it dampens creativity. In terms of the role for interdisciplinary scholarship, I feel that climate deniers are such a small minority. Maybe it feels bigger in the current political climate, but I think it’s really quite small, so I don’t think too much about it. It’s important for scholars in climate issues to speak to different audiences to communicate their findings, and to do that draw from different fields. However, I don’t worry too much about communicating with climate change deniers.

NL: In my research about science and the arts I came across a great deal of thinking that frames scientists as “coldly intellectual with an almost complete lack of aesthetic sensibility and humanistic appreciation” and artists as mystic and “having a profound sense of imagination and a keen discernment of aesthetic values”? Do you think there are still remnants of these stereotypes today? What barriers are there in interdisciplinary work on climate and water issues?

JB: Interdisciplinary scholarship is all the rage now. There are so many new undergraduate majors popping up, so many grant programs, but there are still barriers. Almost all of my training has been in interdisciplinary context and I’ve found that there are still strong interdisciplinary barriers. There are still challenges in speaking across disciplines. There are some that are more closely aligned, but, for example, an anthropologist and an economist have very different ways of thinking.

NL: What are some specific barriers you’ve experienced in interdisciplinary work on climate and water issues?

JB: A large challenge is discussing what constitutes data. I work with qualitative data and often when you interact with people who don’t work with qualitative data, they don’t understand that it’s data. So that’s a big example: different notions of what comprises data. Different scales of analysis are another one – temporal and spatial. The kind of research that I do is very place specific and anchored in relationships I’ve built up over time in Egypt. I don’t seek to generalize or make large statements, whereas for other scholars this is what they do. Then also the temporal frames that you work with: if you are interested in the present, the next couple of years, versus a century scale.

NL: Can you tell me a little about your life and what brought you to science and writing? How did you get into the research you’re doing around Egypt and environmental change/culture?

JB: I actually wanted to do my research in Syria. I spent a year studying Arabic in Damascus and fell in love with the country. That was my last year in my Master’s program – in environmental management. I was looking for different ways to continue my engagement with Syria, and I came across a project idea. I wanted to look at a part of the Euphrates that had completely dried up and the effects this had on populations living in the area. This project led me to do a PhD and for my first couple of years, I went to Syria and tried to get the necessary political authorizations to do my research, but it was basically impossible. So, I shifted to Egypt.

NL: Thinking about our current global situation and the urgency of climate change: How is your work affected by this urgency? Is that urgency reflected differently in your creative work than in your scientific work?

JB: With climate change, the Nile might actually increase its flow because of precipitation changes. I think it’s interesting to think about. It’s almost taboo to talk about the regions that might actually benefit from climate change. There will be negative parts because temperature changes will affect water use, and climate change will also pose challenges around sea level and the Nile delta. In my particular area of work, no I haven’t been affected by the urgency of climate change. It’s not something that anyone I’m interacting with in Egypt is thinking or talking about.

NL: The cover of the Michigan Quarterly Review water issue is of the Nile. I think it’s really helpful for people to hear personal stories and creative voices behind these bigger issues. You’re of course a researcher, but I see you also as a writer. Your writing practice is also your craft. What do you believe that people with their feet in multiple worlds, like yourself, have to bring to this conversation?

JB: I don’t particularly self-identify as a writer, but it’s nice to be referred to as one. That’s my goal. I spend hours crafting my narrative and thinking about how to write in a creative way. I believe writing is really important. The scholars that I most admire are those who write beautifully and clearly. I think that’s something all researchers should strive for: being able to communicate your ideas in a compelling and clear way

NL: Your research focuses on the culture and politics of resource use and environmental change. What differences have you found in the knowledge communities and work in the US versus Egypt?

JB: To be honest, I haven’t engaged much with academic knowledge communities in Egypt. In some ways I wish that I had, but it’s a very difficult political place. The last time I was there, I went to see a professor, and I had to be met at the door and show my passport and sign all these documents. It’s not very easy. So, I have some perspectives, but I don’t have a good insight. There are certainly lots of other kinds of knowledge communities. One of the goals in my work is to think about different kinds of knowledge. The experts tend to get prioritized – the engineers and people with PhDs. We don’t think about farmers as experts, but when talking about water issues, they should be thought of as such. With my first project, people always talked about raising awareness in Egypt. It’s all predicated on a sense that people are ignorant, and you have to raise their awareness. If anyone knows about water scarcity, it’s a farmer.

NL: You’re currently working on your book, Precarious Staples: Wheat, Bread, and the Taste of Security in Egypt. What brought you to this project? You write about the practice and culture behind bread – and how this connects to the deeper issue of food security and national policy.

JB: It’s all about staple foods. In Egypt, bread is so important. It’s something people eat every day, three times a day. Not having bread is seen as a sense of threat. My book is about all of these practices around this staple security – what people do to counter the threat, the practices behind farming wheat and turning it into bread.

NB: Can you talk more about the issue of food security in respect to the political climate in Egypt?

JB: One of my starting points of being interested in this project was that bread took on such a big role in the 2007 revolution. Bread was in the rallying cry. It was partly symbolic and part of people’s livelihoods, but it was also about the food itself. It’s a real hot political issue, but it’s not a new issue. The Egyptian government has subsidized bread since the 1940s, so there has been this long intervention by the government to make sure that everyone had enough bread.

NL: How do you weigh the scientific issues and agricultural policy with the culturally-embedded practices behind food?

JB: I try to understand it all. I try to understand the science of the systems that I’m working with. For Cultivating the Nile, I talked with a lot of engineers and read a lot of hydrology journals. I wanted to understand the physical components so that I could analyze the cultural components. I wasn’t gathering natural scientific data myself, but I want to understand it. For my current project, I’m reading about wheat production and the science of agricultural systems that I’m working in.

NL: What would you say is the value of interdisciplinary work, of gaining new perspectives to work on an issue?

JB: You can’t really understand one piece independently. You can never understand everything but having at least pieces of knowledge helps for getting a more coherent appreciation. That’s the reason I can read a hydrology journal because I’ve taken hydrology classes. I have a level of literacy in other areas and I think that’s the value. When I’m speaking to engineers, I have a little bit of scope to speak to them. You’re never going to know everything, but at least you have literacy to speak with other people and learn from them.

NL: What’s a trend that you’ve been seeing in the literature on water studies and environmental issues in general?

JB: My pet peeve in the water literature is the continuing prevalence of narratives that frame the issue all in terms of population. It’s really not about population. It’s so present in academic work and media coverage. In terms of other trends, there has been lots of interest in infrastructure recently. The infrastructure of moving water and changing water. Then, ongoing issues of participation and governance are still of interest.

NB: Where do you think academics have to go from here? What work still needs to be done?

JB: There’s so much and I don’t think there is one area. Gaps are everywhere. The more you learn, the more you know you don’t know. The Middle East, for example, is not well studied. There are other gaps topically. Even in areas where lots of people have worked on, the work just brings more things for people to study.