Dr. Sara Ana Adlerstein Gonzalez is an applied ecologist and visual artist who explores the connections between art and science. As a scientist, she investigates processes at the ecosystem level using statistical modeling. Her main interest in research is to understand ecological processes and population dynamics of aquatic organisms at the ecosystem level, in particular those aspects that are relevant to resource management. Recently she has been investigating spatial and temporal scales needed to study the spatial distribution of fish abundance and obtain indices of abundance of fish populations in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Since fish, as other aquatic organisms, cannot be directly observed, large-scale population studies must rely on analysis of data from scientific surveys or commercial operations. The analysis of this information requires specialized statistical modeling. Currently Adlerstein Gonzalez’ focus is in the Great Lakes environmental stressors.

Natalie Lyijynen is a freshman at the University of Michigan double majoring in the Environment and Biology, Health, and Society. She’s passionate about the science behind sustainability and plans to pursue environmental law. In addition, she’s always loved the arts and has further realized her love for creative writing after being a part of the Lloyd Scholars Program for Writing and the Arts. Through the Undergraduate Research Program, she joined Michigan Quarterly Review to help research the global water crisis and solicit for their Spring 2020 issue. Realizing the value of interdisciplinary scholarship in communicating about environmental issues and with the help of MQR, she conducted an interview project. She interviewed five professionals who bridge the gap between the sciences and arts in order to shed light on the barriers faced in work on climate and water issues. Her purpose was to address historical precedents, research how stereotypes have changed or persisted, explore the professional impact of the interviewee’s work on climate and water issues, and gain insight on global trends and what the future may look like for interdisciplinary scholarship.

This interview was conducted in February 2020 at the University of Michigan.

Natalie Lyijynen (NL): In his essay “The Artist, the Scientist, and the Peace” Sinclair Lewis wrote cynically about artists and scientists post WWII: “Their native land is truth, but no artist or scientist in history has yet dwelt utterly and continuously in that land of truth, because it always has been stormed by the lovers of power.” Thinking about our current political divide and tension, what do you think about this idea? Does it still persist today?

Sara Ana Adlerstein Gonzalez (SAAG): That’s a huge question, and I don’t think I have one answer because I think there are many. It depends on personal perspectives. Art is a reflection of society; it’s a mirror of what’s going on. We, as scientists and artists, have our own ways of dealing with the truth: but “what is the truth?” It’s very hard to have a definite answer for that. Definitely, art has been used as a tool to dominate rather than telling the truth, and also science. We tend to think that science is objective, but it’s actually very subjective. As a scientist, you choose your subject matter. Everybody has their own take on what’s important. For me, art is the practice, and then the humanities write about it – so art is its own truth. Artists are being modeled by the society around them. An artist who wants to make a living out of art has to please the client – that’s one thing that limits truth. Other times artists are paid to represent the religious and the powerful. Both art and science are framed by the society we live in.

NL: In my research about science and the arts I came across a great deal of thinking that frames scientists as “coldly intellectual with an almost complete lack of aesthetic sensibility and humanistic appreciation” and artists as mystic and “having a profound sense of imagination and a keen discernment of aesthetic values”? Do you think there are still remnants of these stereotypes today?

SAAG: People are people, and on both sides, there are people who fit those descriptions. I don’t think it’s necessarily that the artists are one way and the scientists another way because we all start the same and then we choose a career. I believe that we are all born artists. I know that you are a better artist when you are a scientist and that you are a better scientist when you are an artist. You can combine imagination with information. The scientific method has many advantages, it can help you develop as an artist, but the method also has many constraints. When you know how to improvise, this helps the scientific mind. It opens up possibilities that you wouldn’t thought of. The ideal is someone who knows both languages

NL: Do you feel that a sentiment of competition and separation between the two fields exists in the same way it once did?

SAAG: I don’t see it as a competition; I see it as a division. We experience that in academia. The way that the university is structured imposes lots of barriers. I’m somebody who’s been trying to navigate that. Most of what I’ve done in bridging science and humanities has been against existing forces, rather than helped by them. In principle, the university would like this integration. There are initiatives, but then when you try to work on it, it’s really hard. The reality is that the artists are always willing to get inspired or occupied or justified by the sciences. I know zero scientists in this university, other than myself, who have been trying to work with the arts. As a faculty member who is classified as in the sciences, I do not have access to get funding that allows support for my research scientist position in any humanities opportunities. It’s not that I haven’t tried— I’m just not allowed to. The university is so interested in engagement, in outreach and diversity: all of those things are fertile ground for arts and humanities to be combined with the sciences. The only grant that I have been able to get is $5000 to do a children’s book on macroinvertebrates of the Huron River. Everything else I do for the arts, I do it without funding. I have to because I love it. It’s not that I think there’s a big barrier; it exists, and I don’t know how you get rid of that. I find joy in giving and collaborating, but it’s not the norm. I don’t think it’s just a division of science and the arts. It’s a division of people and people who are just concerned with their own turf. If everybody could just get a bit of art into their souls, everything we touch will just be so much better.

Many students in my classes at SEAS tell me that they used to be musicians, painters, or writers and have given up their art practice. Why? We need to integrate these things into the curriculum. It’s not that hard, it’s just that the vision is not there. I don’t see it improving at all. There’s sometimes the talk, but the walk’s not there. One can include arts and the humanities in every class. I think that it needs to be included in the curriculum, not as an add on thing. One SEAS faculty even told me that art didn’t belong in the program – that I shouldn’t be doing what I do. However, I’m very grateful that I’m allowed to teach an environmental humanities class and that students benefit from the experience. For example, one of the projects is to create a children’s book, and I’ve heard from one of my students from Costa Rica that at her institution, they’re printing copies of the book for a youth environmental program. Classes should be that kind of meaningful life experience.

NL: Can you tell me a little about your life and what brought you to gaining your PhD and working in SEAS – and also continuing your artistic career?

SAAG: I started my life as an artist. Every kid is an artist, and I was always so interested in nature. When deciding what to study in college, I applied to the schools of Journalism and Natural Sciences and ended up enrolling in the sciences. I also wanted to join the visual arts program but disappointed by the entry exam I decided to pursue art on my own. Thus, painting for me was experimental, and kept separate from science. I did have a couple of professors that were artists, and that was very inspirational. That helped me out thinking that it was possible to do both. When I went to Seattle to graduate school, that’s when I became more serious about showing my artwork. I grew up in my science career, and at the same time, I grew up in my ambitions in the art world. Then when I moved to Germany and worked at the University of Hamburg, art and science continued to be in parallel. Art was kind of my medicine and a way of communicating and storytelling. Then shortly after I joined the University of Michigan, I was invited to participate in the Arts and Earth Initiative, and I realized the wealth of opportunities and benefits for integrating art and sciences programs. I understood that the University valued bridging these disciplines, and I started collaborating with colleagues in art units. It became so clear to me that I had a gift and I had to bring it into my job. So I started incorporating art and humanities in my activities and teaching building upon my own experience and in collaboration with faculty from art units. I wish more faculty would be willing to bridge disciplines. In addition, I think it would be a much better world if we collaborate more. Art is a different language that you can communicate and teach with.

NL: I really enjoyed looking at your art online, your series include interpretative ecosystems, biological abstractions, cultural celebrations, and human landscapes. Where do you get your ideas for each of these series?

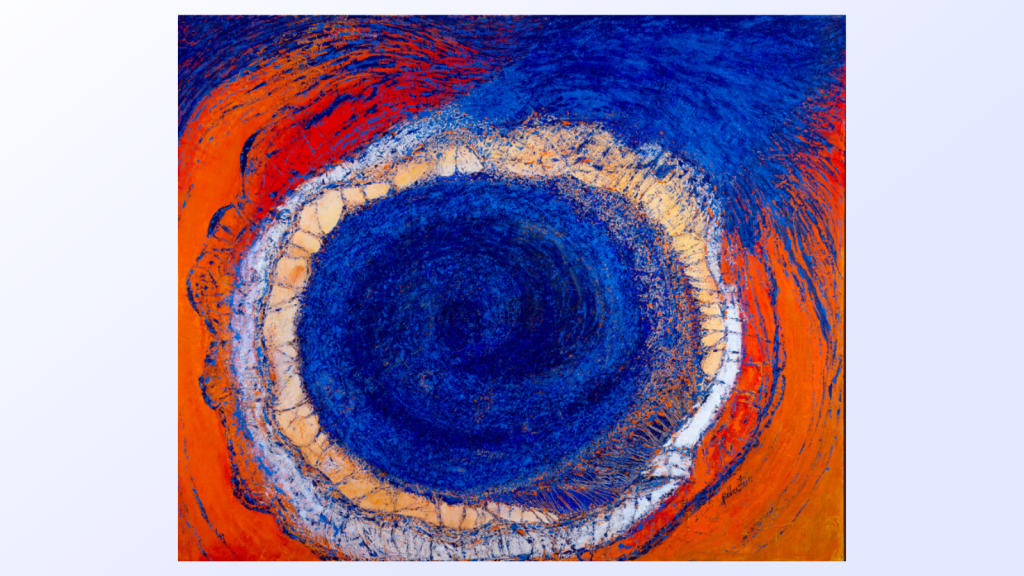

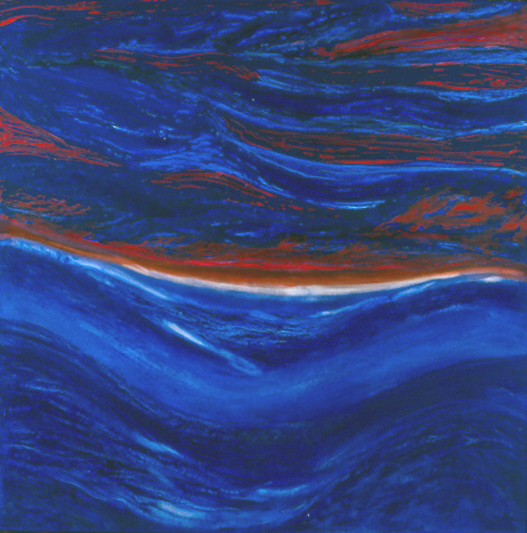

SAAG: My process is like we’re having a conversation. You start with a word, and you go from there. When I’m painting, I’m not thinking. I don’t have a sketch. What I have is a piece of canvas or Masonite, usually a large surface because I need the space for the painting to grow. I start somewhere, and I watch what it’s happening in front of my eyes and discovering as I go. I’m not pushing the process, but I’m aware of who I am, and I have all of these things in my head and heart that somehow grow under what I’m doing. I can’t think of trying to do something – it’s a failed experiment because I get totally bored. It’s different from how many people see the process of serious artists. I have a life and that life does the painting. Because I do it this way, my paintings are always about something that’s going on. For example, I’m an ecologist working in Michigan, and study rivers and the effects of dams, so when you look at some of my work, it’s all there: the change in flow and the sediments, and all of the things that happen when you have a dam. It looks like a happy picture, but it’s about stream ecology. I can give an ecology lecture through some of the paintings. The painting that I just finished is of Australia, climate change and the forests burning. That’s what is in the news, what is in my heart – suffering for the planet. Anything that is happening in my life comes into a painting.

NL: You include humans in some of your work – they flow and are part of the landscape. How does this reflect the relationship between humanity and the environment?

SAAG: They’re all self-portraits and reflect how I feel in that we are part of the environment. We are nature. You don’t end where your skin ends, you breathe the air, and you will go back to being compost. I really do feel that I am connected with everything else. These paintings urge to develop a sense of self-awareness.

NL: What do you believe that people with their feet in multiple worlds, like interdisciplinary artists, have to bring to the conversation around climate and water issues? What can art communicate about the environment – especially in the urgency of climate change?

SAAG: I think that we have enough scientific information to make this planet a better place. I think science has reached its limit. It makes me sick to see one more data point that costs I don’t know how many million dollars, to document that there’s less ice and a rising temperature. We already know this. How long are we going to be documenting and saying that it’s helpful? We do need science, but it’s not enough. It’s critical to do something about it. A scientist isn’t going to move people. Scientists are publishing in journals read by other scientists. Even if the general public could read it, what would they do with the information? I think art has the power to communicate, inspire and move people. We know that the Nazis banned certain art because of that. Art is communication. We should take a deep look at what we want as an academic organization, do we want to help change the world? In the UM carbon neutrality commission, arts and humanities were largely ignored. Why are we looking mostly at technological fixes when we need to change the culture? We need to help people understand their roles on how to address the climate crisis. I do believe in the power of art. I don’t know if the arts are going to change the trajectory of the planet, but at least they’ll change some people’s minds. I’m trying to create an arts and the humanities climate action initiative, but I don’t know where the funding will come from. I think we could, as a university, produce a model for how arts and science integration can be part of the solution for the climate crisis. We need the artists to engage – artists using a solid background in the sciences. That’s why interdisciplinary collaboration is always a good thing. However, in order to have an interdisciplinary good team, members have to understand each other’s language. A translator is somebody who speaks two languages. That is why in environmental curricula, we need to include both science and arts, so there is at least some basic common language. If you don’t understand the others, you don’t respect the others and you look down on them. That’s why we need to change the way education is done and not only at the undergraduate level, but also the graduate level. It takes power to change the culture. I know the students get it, but we need action from the leadership. It’s hard to address environmental and other issues when we have a society where everyone wants to get something instead of giving something.

Cover Image: Great, Just Great! Copyright Sara Ana Adlerstein Gonzalez. More of her work can be found online.