On September 5, 2018, I received devastating news in a simple phone call from my sister. “We lost mother a few minutes ago,” she said tearfully. It was hard to believe; my anchor, nurturer, most trusted confidant, and one of the last “water carriers” in Cyprus was gone at the age of 95. The news sent me reeling in shock, and it took me a long time to find my footing. To this day, I wake up in the mornings thinking I will call my mother and have a long chat with her. Then I realize she is gone, and once again I feel the void she has left behind. Having survived some of the most turbulent political times in the history of Cyprus and proudly raising a family with her hard work, courage, and endless devotion, she had passed on quietly.

My mother was the last of the lineage of “water carriers” in our family; by the time I was born in 1955, there was no need to carry water from the water springs in Portolaumo. We finally had running water in our homes through installed faucets. Thus, the long era of carrying drinking and cooking water in terracotta urns and clay jugs came to an end—most likely completely forgotten by most Potamians. However, that era’s significance to the livelihood of three generations of women in my family who preceded me (my great grandmother, grandmother, and mother), passed onto me by my mother, is something I am not quite ready to forget it just yet.

* * *

My mother Emine was born in 1923, the third and youngest daughter of Grandmother Dudu and Grandfather Hakkı, who owned a grocery store, coffee house, bar, butchery, and kebab oven, all in one building that faced the village square, in the center of Potamia. My mother’s family lived in the back of the same building.

Grandfather Hakkı’s coffeehouse was Potamia’s de facto “city hall.” For many years, until the end of 1963, everything important to Potamia happened in or just outside that coffeehouse. Potamians discussed and solved the daily issues and problems they faced, usually while sipping Turkish coffee served by my grandparents under the shade of the grapevines that twisted up the huge trellis in front of the coffee house. For example, if a farmer’s wells dried up, other farmers would meet there to help him find a solution. Mundane news and gossip impacting Potamians was also discussed there. Even the buses and taxis departed for their destinations from the coffeehouse.

Almost all Potamians visited my grandfather’s coffeehouse and did their shopping at his grocery and butchery. If a family needed cooked food, they could buy it from Grandfather Hakkı’s kebab store, where everything was cooked traditionally in a brick oven. To this day, I have never eaten better tasting kebabs than those that came from my grandfather’s oven. However, running the coffeehouse, butchery, and the kebab oven required a lot of drinking water. Although there were two water wells located in the village, they could not satisfy all of the demands of the households. Most water (for drinking, cooking, washing, etc.) had to be fetched in terracotta urns and clay water jugs from Portolaumo, where the fresh water springs were located, about a mile outside the village. This task usually fell to women and young girls. Therefore, my grandparents’ three daughters, including my mother, had to make regular trips to the springs in Portoloumo to support the operations of the family business. They could not skip this task for a day, or even half a day without impacting the business.

The literal meaning of Potamia is “she who lives on the river.” However, in my view, these women and young girls carrying water to their households, daily, in their terracotta urns and clay jugs could be best described as “water carriers!”

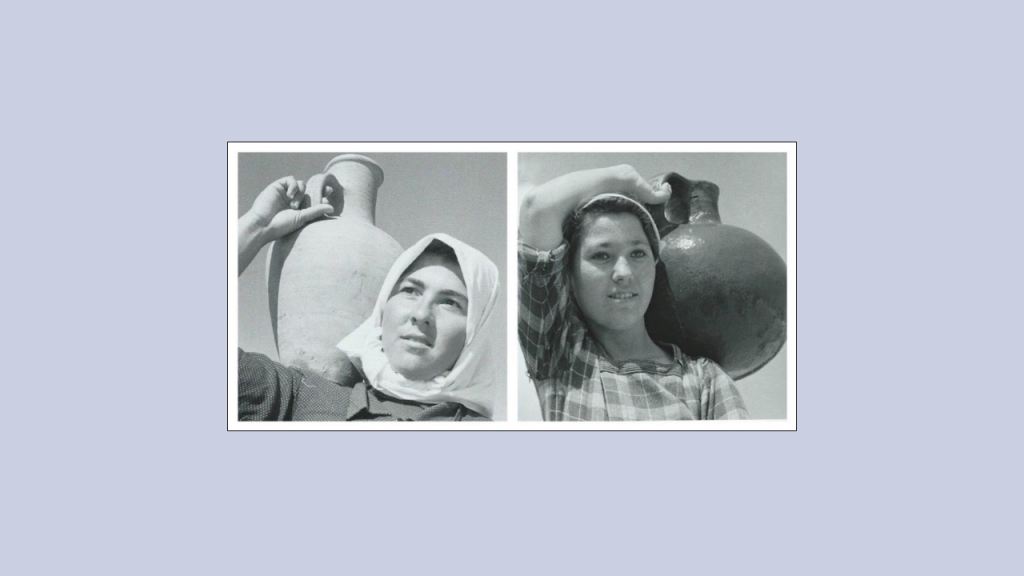

From our family album: Water carriers in Cyprus in the early 1900s.

According to my mother, carrying water from Portolaumo was a labor intensive and time-consuming task for these women, but it also offered an opportunity to socialize with their friends and neighbors. They would decide on a schedule from the night before and meet the next day according to that schedule to go to the springs. This way, they avoided everyone showing up at the springs at the same time which would have resulted in long queues and long waiting time for filling up their urns and jugs. Mother always talked fondly about how plentiful and cold the water was running at the springs in Portolaumo.

Normally two water trips were made per day, one in the morning and another in the late afternoon. However, on special days (weddings, funerals, holidays, etc.), two trips would not be enough. My mother could recall making up to 3-4 trips on such days. The groups would meet in their respective neighborhoods based on the agreed schedule, and they would walk to Portolaumo together. While walking, they would talk and catch up on the latest news. Sometimes, they would even all sing together. As they passed, almost like a ritual, the village men, especially younger ones, working in the nearby fields and farms would take a break from their work and line up on the sides of the road to watch them go by.

Much later, in the 1950s, the British administrators of Cyprus (the island was a British colony then) dug wells in Agri, to supply drinking water to Nicosia, the capital. As part of that project, the main source of the water supplying the springs in Portolaumo was diverted to Agri and, since that time, the springs in Portolaumo have completely dried out. Today, there is not a drop of water where the old springs used to be.

* * *

As a little girl, my mother attended the Potamia Turkish Elementary School, where she was a good student and had one special teacher who saw potential in her. As my mother’s graduation from elementary school approached, this teacher talked with Grandfather Hakkı several times and encouraged him to send my mother to Nicosia to attend Victoria Girls School. The British had established the Victoria Girls School in 1901 to serve the island’s Turkish population as a middle school. High school would be added to it much later, in 1952. My mother wanted to get a secondary school education and eventually become a teacher, but Grandfather Hakkı was not convinced a secondary education was necessary for his daughter. Even if he was convinced, he could not afford to send my mother to that school which operated only as a boarding school at the time. He had five children to support and could not pay the fees.

To be fair to Grandfather Hakkı, in the 1930s very few girls obtained a secondary school education in Cyprus. Those who did were from the most affluent families, so if my mother had been able to get a secondary school education, it would have been quite extraordinary. Although my mother’s teacher ultimately failed to secure a secondary education for my mother, she made a huge impression on her. This teacher, whom my mother loved and respected a lot, had a daughter named Duyal. Years later, when my mother had a second daughter, she named her Duyal too, after her elementary teacher’s daughter.

Thankfully, a newly established vocational institute in Potamia taught young girls after graduating from elementary school, as well as women in the village who chose to attend it. The lessons focused on weaving, sewing, knitting, crocheting, and other useful arts and crafts. There was no tuition to attend, which made it popular among young girls and women. My mother attended this institute for a while and was a good student there.

But after a few years, it was time for my mother to start working and earning money to contribute to her family’s income and save up for her own future needs. She put her new weaving skills to good use and began working from home. Grandfather Hakkı bought her a manual wooden weaving loom, which was modern for its time and operated with a gripper shuttle. According to my mother, her loom was almost the size of an entire room. It had to be large so she could weave wider products: the wider the loom, the wider the cloth that could be woven. My mother weaved materials that could be made into bed sheets, bed canopies, pillowcases, and other useful household items. As a teenager, she continued to do this for years.

My mother used to tell me how she actually enjoyed weaving, but did not care at all for carrying water from Portolaumo. However, she did not have a choice and had to perform both duties. She would wake up early in the morning to join the other girls and women in the neighborhood to go to the springs. She tried to do this as early as possible so the sun would not be up when she returned. It gets really hot in Cyprus, especially in summer, and if one was carrying two clay jugs full of water, one in each hand, or one in one hand and the other on the shoulder, it was best to do this when it was not so hot. Then, after the morning water trip was completed, mother would start working on her weaving. Apparently, as soon as she started weaving, time passed very quickly and before she knew it, she would have to head out on the afternoon trip to fetch water. She would reluctantly get up from her loom and force herself to meet with the group departing for Portolaumo and complete her second trip of the day. This was her daily routine for many years.

Young woman weaving using a manual loom, similar to the one my mother owned.

Mother always talked fondly about her weaving. I used to listen to her stories about the intricacies and difficulties involved. To make good progress, she had to weave fast. She would throw the gripper shuttle from right to left using her right hand and then catch it on the left end of the loom using her left hand. She would then throw the gripper shuttle from left to right, catching it on the right end. She would repeat this action many times—sometimes for hours. She had to be fast, but also precise. She could not afford to make mistakes, as even a small mistake could cause the woven strings to become tangled. Untangling them could take a long time, resulting in many hours of lost work. Just before she got married, my mother sold her loom and had subsequently missed it and weaving for years. It was interesting to note how my mother never liked the bed sheets we bought from stores; she thought the quality of the bed sheets she had weaved were far superior. However, by this time, industrialization was in full progress and manual weaving was no longer popular or practical. Bed sheets woven in textile factories were a lot cheaper to purchase than those woven using manual looms.

* * *

In hindsight, my mother’s attendance at the vocational institute was very beneficial for her. She learned everything the instructors taught her and used those skills throughout her life. My mother did not forget her experience as a young girl unable to study at the Victoria Girls School, no matter how much she wanted to. I believe that was why education for me and my sisters had always been so important to her. She continually supported us in our aspiration to get as much education as we wanted.

* * *

When my mother turned 20 years old, she was engaged to be married. Around that time, water faucets were installed in the homes in Potamia and my mother, just like the other women and young girls, stopped carrying water from Portolaumo. As it happened with the textile weavers operating manual looms, the last of the “water carriers” had been displaced by innovation and the march of time.

My parents on their wedding day, in 1953.

My parents’ engagement lasted ten years. They could not get married sooner because they did not have a house to live in. Then, in 1953, my father’s aunt passed away and left her house to him. My father repaired that house, and my parents were finally married. A year later, my brother Ismail was born. Seventeen months after that, in November 1955, I came into the world. Eventually, we would have three more siblings, for a total of five. By the time we kids grew up, the tradition of carrying drinking water from Portolaumo in urns and clay water jugs to the households in Potamia was long forgotten. But for my mother, this tradition still evoked nostalgic memories of her youth, of a way of life eventually swamped by the relentless march of technology and time. And, as the great storyteller my mother was, she kept these memories of her experiences as a “water carrier” very much alive in the hearts of her children.