Born in Iran in1980, just after the Revolution, Garous Abdolmalekian has only known war. For decades, religious and military conflicts have raged within and from outside his country’s borders. Abdolmalekian’s collection Lean Against this late Hour, represents a major triumph not only because of the beauty and power of the language (it’s his first book translated into English), but also because of the poet’s refusal to surrender subjective experience in the face of overwhelming historical circumstance, invading forces threatening to occupy every aspect of his life.

In this volume the personal is always at war with the political, and boundaries – both geographical and personal— are often blurred, bombarded, beset. In the first poem, “Border,” for example, the speaker wishes “the borders between the streets and the bedcovers were clear” – so fully have the lives of ordinary citizens been occupied by military incursion, not just onto the battlefield but also in the most intimate of spaces such as the bedroom. This intrusion of military metaphors into personal experience appears again in “On Power Lines” where the speaker pleads to his audience, “Tell me how to manage my smile/when they have planted land mines all around my lips.” The idea of explosive devices surrounding his lips suggests a pattern of disturbing censorship and an all-out assault on intimacy. Linguistic boundaries are also under siege. In this landscape, another speaker laments, “The borders have painted over God’s landscapes for so long/that dried blood/is just a name for color.” Living in such a distressed political and personal state, it is perhaps not surprising then that another speaker (in a poem called “Pattern”) asserts, “Your dress waving in the wind./This/is the only flag I love.” For this poet, what matters most are personal, and not political allegiances.

In the face of such violence, Abdolmalekianturns inward, creating imaginative spaces where he can live apart from and even transcend the political repression all around him. In “Long Poem of Loneliness,” the poem that lends the book its title and which, at four pages in length, is the longest poem in the book, the speaker describes a man whose profound “loneliness” has “wither[ed] the flowers on his shirt,” a phrase with a touch of magical realism that shows the influence of his mental state on the physical world, the flowers withering in sympathy with his isolation. For this man, “yesterday is over/tomorrow is over” and “he has touched both sides of death/like the front and back cover of this book/which he closes in the middle/tosses on the floor/but it doesn’t fall/it rises/and flies off/with the two lines of its story./Now a couple of white birds/are crossing the sky’s mind like tiny words.” Surrounded by death, words are a source of liberation that can give flight to the poet’s imagination.

At times, Abdolmalekian’s poems are reminiscent of another contemporary fabulist, Ilya Kaminsky. In fact, “On Power Lines” ends with lines that would not be out of place in Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic: “This time/send us a prophet who only listens.” Or, perhaps an even clearer literary relative is Ovid who said, “All things change; nothing perishes.” Abdolmalekian’s narrators often seek transformation, “If someone would turn these snakes into rods” and they, themselves, frequently metamorphose: “Even with the water rising, rising…I will become a fish,” one says; “I could turn into a boat,” says another. Not even death can stop these transformations. The poem “Ant,” for example, opens with the line “I am dead” but the speaker speaks from beyond the grave in an act of prosopopoeia, saying “I wish at times/ to become an ant/to build a house in the throat of a flute/to ask the wind to blow the notes.” In “Bits of Darkness”: “He is insane/this man who was shot yesterday/who still plans his escape.” Language for this poet is a means of escape and transcendence from the violence and trauma all around him, his words allowing him to survive even the finality of death.

More than once, reading this book, I was reminded of Auden’s “In Memory of WB Yeats,” and the much-quoted line “poetry makes nothing happen.” But remember: Auden’s full line also includes the phrase “it survives” – and survival in these circumstances is itself an extraordinary accomplishment. Poetry may not make anything happen, Auden concludes, but it is “a way of happening, a mouth” and in these poems, Abdoulmalekian bears witness to, gives voice to, his own pain and the immensity of suffering and loss around him. As one of his speakers puts it, “In me there are characters/who stab each other/assassinate each other/bury each other/ in the cemetery of my psyche/but I/with all my characters/go on caring for you.”

Abdolmalekian’s extraordinary capacity for empathy is equal to, and may be the source of, his dazzling imagination.

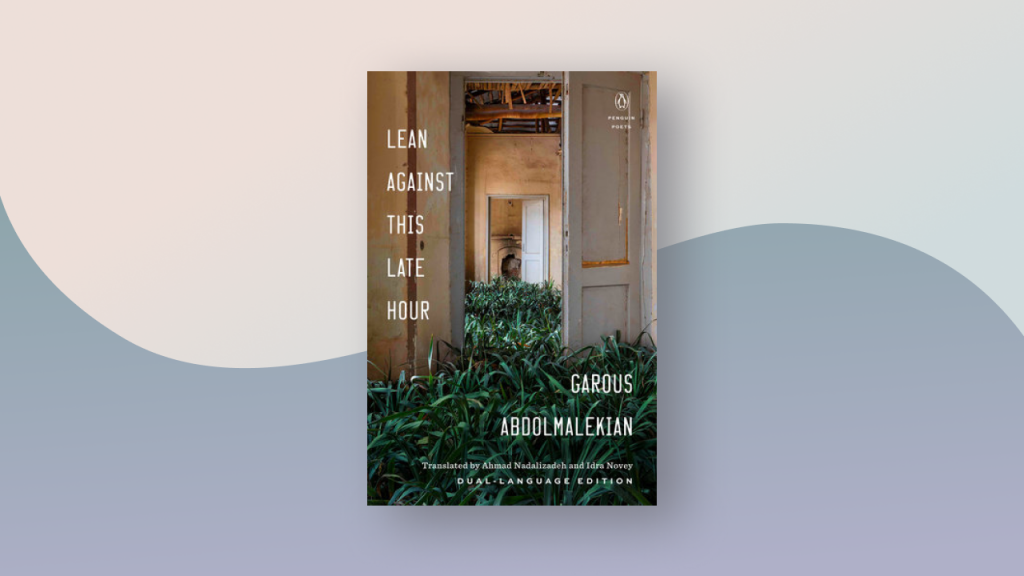

In this volume, the Persian text is presented on facing pages alongside the vivid and striking English translations by Ahmad Nadalizadeh and Idra Novey. Not only do the Persian letters look beautiful, but the dual language presentation points to a sense of isolation many English readers feel from world events. According to the Publishers Weekly database, 2018 marked the second straight year where the number of new translations into English declined. Unsurprisingly, Romance languages from western Europe dominated the top spots, with Arabic the 10th most frequent language from which these translations sprang and Russian 9th (Persian did not make the list).

Abdolmalekian knows all too well that many of his potential invisible listeners, “no longer read at all/and the silence is so maddening.” Given the political tensions on the world stage and the rise in xenophobia in the United States in the past few years, the powerful voice of this extraordinary poet is perhaps more necessary now than ever. If only we would listen.