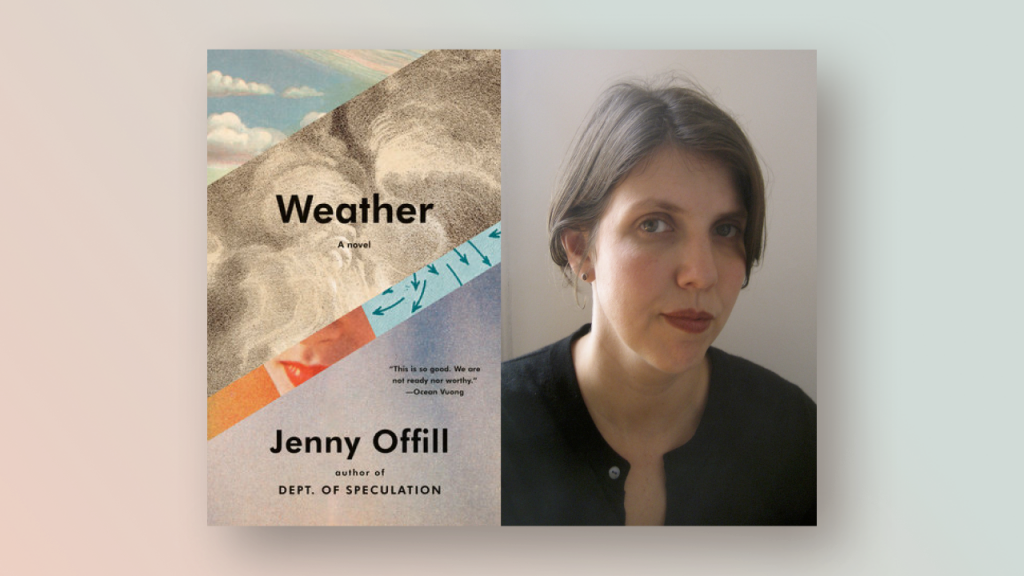

Near the end of Jenny Offill’s acclaimed second novel, Dept. of Speculation, the narrator makes an observation about the rural town to which the married couple at the novel’s center has moved:

The weather is theater here. They watch it through the window from their bed.

These sentences, unremarkable in Dept. of Speculation, would be impossible in Offill’s latest novel, Weather.

The novel is narrated by Lizzie Benson, a once-promising graduate student turned university librarian. Her old academic mentor, Sylvia Liller, reaches out to Lizzie with a proposal: she’ll pay her to answer the email she receives from listeners to her podcast, Hell and High Water. Sylvia has become something of a celebrity among people worried that the world—or at least civilization as they know it—will soon end. In the course of assisting Sylvia, Lizzie becomes increasingly concerned with questions of what to do in a world in which climate change seems to be headed for apocalyptic territory.

As narrator, Lizzie Benson is delightful company. Her mind is a wellspring of wry, cutting observations about motherhood, marriage, and, thanks to Sylvia, a possibly imminent apocalypse. Early on, Sylvia brings Lizzie to a dinner with some of her podcast donors. Sylvia is hoping that these visitors from Silicon Valley might fund her new project, a foundation that aims to “rewild half the earth.” Lizzie, as ever, is a canny observer:

But these men are not interested in such things. De-extinction is a better route, they think. Already they are already exploring the genetic engineering that would be necessary. Wooly mammoths are of great interest to them. Saber-tooth tigers too.

Somehow, I get seated halfway down the table from [Sylvia]. I’m trapped next to this techno-optimist guy. He explains that current technology will no longer seem strange when the generation that didn’t grow up with it finally ages out of the conversation. Dies, I think he means.

But Lizzie’s most cutting and heartbreaking observations are about motherhood. In a particularly striking section, she recounts an interaction with her son, Eli:

[…] I yelled at him for losing his new lunch box, and he turned to me and said, “Are you sure you’re my mother? Sometimes you don’t seem like a good enough person.”

He was just a kid, so I let it go. And now, years later, I probably only think of it, I don’t know, once or twice a day.

This is Offill at her best—providing the reader with something gut-punching, presented as casually and unsentimentally as an offhand line.

In a recent interview, Offill said she had a question in mind while writing the book: can you keep tending your own garden once you’ve seen the flames beyond its walls? Lizzie’s job with Sylvia makes doing so seem increasingly fraught. And, the novel hauntingly suggests, doing so may soon be impossible anyway:

“Do you really think you can protect [your family]? In 2047?” Sylvia asks. I look at her. Because until this moment, I did, I did somehow think this. She orders another drink. “Then become rich, very, very rich,” she says in a tight voice.

In his review of Dept. of Speculation, John Self of The Guardian wrote: “A book this sad shouldn’t be so much fun to read.” I could say the same about Weather. It’s a book that deals unflinchingly with the idea that humanity may be doomed, and somehow, it does feel “fun” to read. The novel is told in vignettes. At 224 airy pages, it’s a fast, propulsive read. This amount of white space is more common in books of poetry than novels, and reading the short, often self-contained paragraphs, sometimes felt more like reading stanzas—I was compelled to pause and linger. In a novel this good, this lingering is welcome. Fun is perhaps not as accurate a word as spellbinding. Spending time in the head of Offill’s main character feels like being under a kind of spell. In the aforementioned interview, Offill described the process she used to decide which fragments to include in the novel. She pasted them on large poster boards, then let time pass. Only time, she said, allowed her to see whether the fragments belonged. This may explain, in part, the hypnotic quality to the writing. Anything lackluster has been cut.

The last page of the novel provides a link to a website: www.obligatorynoteofhope.com. The wry web address, the cliché of the “obligatory” note of hope, hints such a thing is futile. But the link leads to a website that suggests the opposite. On its landing page, Offill writes:

I always thought it was ridiculous to try and fight for social change when I couldn’t even get my own house in order. How could a meat-eating, plane-flying, march-hating person like me ever find a place in the climate justice movement? But then I started to read about all the different ways ordinary people were refusing to give into fatalism and were exploring the possibilities of what they could do, what they might fight for in this half-ruined world of ours.There were saints among these accidental activists, but also stone-cold hypocrites like me. Slowly, I began to see collective action as the antidote to my dithering and despair.

Below this text, the website provides links to profiles of “people of conscience” and “ways to get involved,” with suggestions to donate to various climate-change-related nonprofits. With such a clear purpose in mind, it is admirable that Weather does not come off as didactic. Perhaps the novel’s biggest strength is that it does not offer assured answers, but instead a brilliant companion for navigating the most daunting problem of its time.