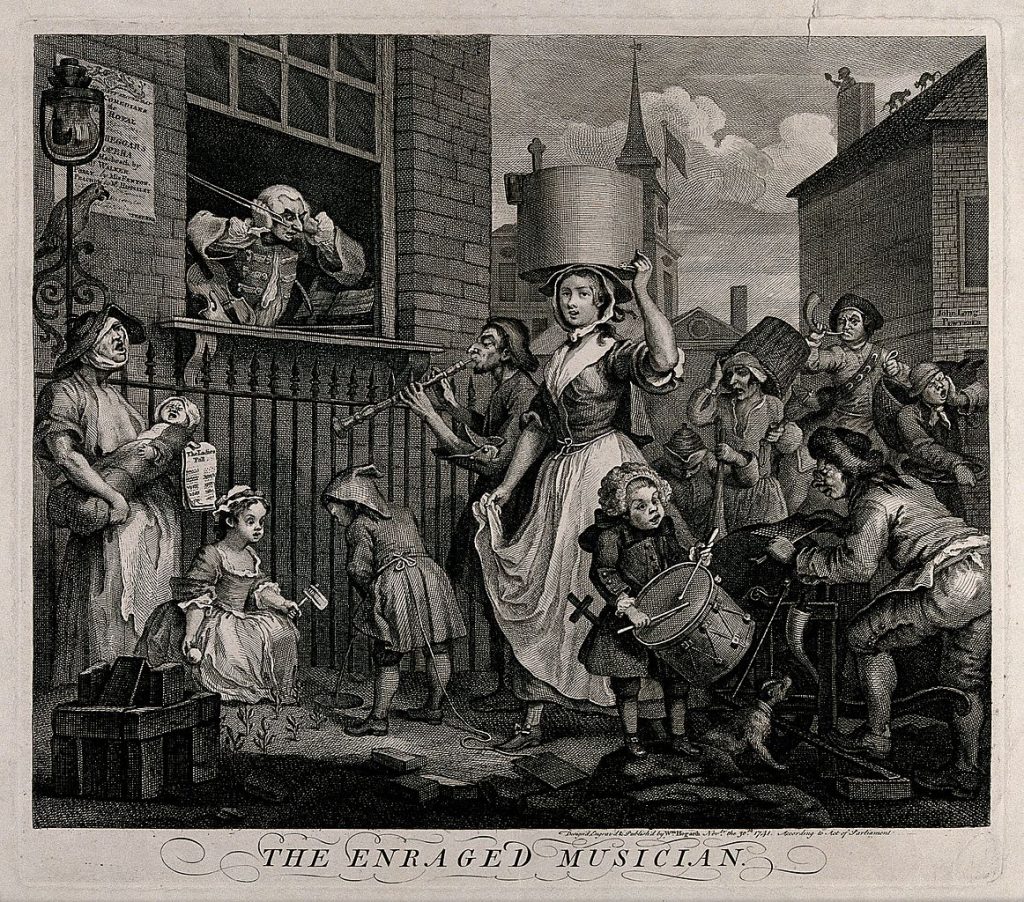

On being introduced to new art—ahem, content—via a short story about street hip-hop and crate digging, among other things .

Before I knew it, I was surrounded. They were all around me, pressing closer and closer, and their eyes were piercing. Every time I turned my head, it seemed I was making eye contact with yet another stranger. How, I asked myself, had I allowed this to happen? I knew better than to allow myself to get stopped on the street. I’d lived in cities for most of my life! I knew I shouldn’t have acted interested!

Here’s what happened: on my way to the train several months ago, just as I was about to enter Westlake station in downtown Seattle, a man approached me with a CD. Fool that I am, I stopped momentarily, and they had me—he and the three other people also “giving away” CDs on the street. They asked me if I liked rap, where I was from originally, and after I answered in the affirmative and that I was from Philly, one dude called me Donovan McNabb and that was that. We were pals! They all gave me CDs, and then they asked me, strongly, for “donations.” Before I knew it, I had four new CDs that I didn’t particularly want and was out $20. I was distinctly surprised.

I was surprised because, despite the sense of possibility inherent to city living (1), much of city life in fact involves the avoidance of possibility. We tend to walk around neighborhoods we know best; we stick to routines, going to the usual pizza place, taking the same route to the train, becoming regulars at hair salons and corner stores; we tend not to talk to strangers; we cross the street to avoid solicitors; and we wear headphones. In a sense, life in the city is curated by our preferences and routines. Cities, even large ones brimming with life, can be truly small places to live if one’s experience of them is curated—or limited—enough. In this way, this walling oneself off from urban life, is akin to how we (2) now experience and are exposed to much new art.

***

I have been a Spotify premium member since the summer of 2015, which means I’ve been paying Spotify $9.99 for more than six years, spending nearly $550 (!) in that time to listen to a wild array of music, new and old. I consider the money well spent, as I’m an ardent digital crate digger—having spent years as a physical crate digger before moving most of my digging online. But I’m probably an atypical user: my Spotify use is by and large self-directed, and I tend to hear about a record or get interested in a band prior to looking them up in the add; I listen to few playlists put together by others; I don’t like much popular pop music; and I never ever shuffle albums. But because being perpetually online is exhausting, I will occasionally let algorithms do my research for me.

A recent example: over the last few years, I’ve gotten increasingly into the blues, specifically early blues. The other day, I was listening to Spotify’s “Blues Origins” playlist and when that ended Spotify continued to play similar music, via the platform’s algorithm-driven autoplay feature. The album that Spotify put on—the 1990 compilation The Slide Guitar: Bottles, Knives & Steel—included Tampa Red and Georgia Tom’s “You Can’t Get That Stuff No More,” a grooving, infectious song about bootlegging. I was floored: Tampa Red’s slide guitar work was mesmerizing and excellent, how had I not heard of him before? I began digging immediately.

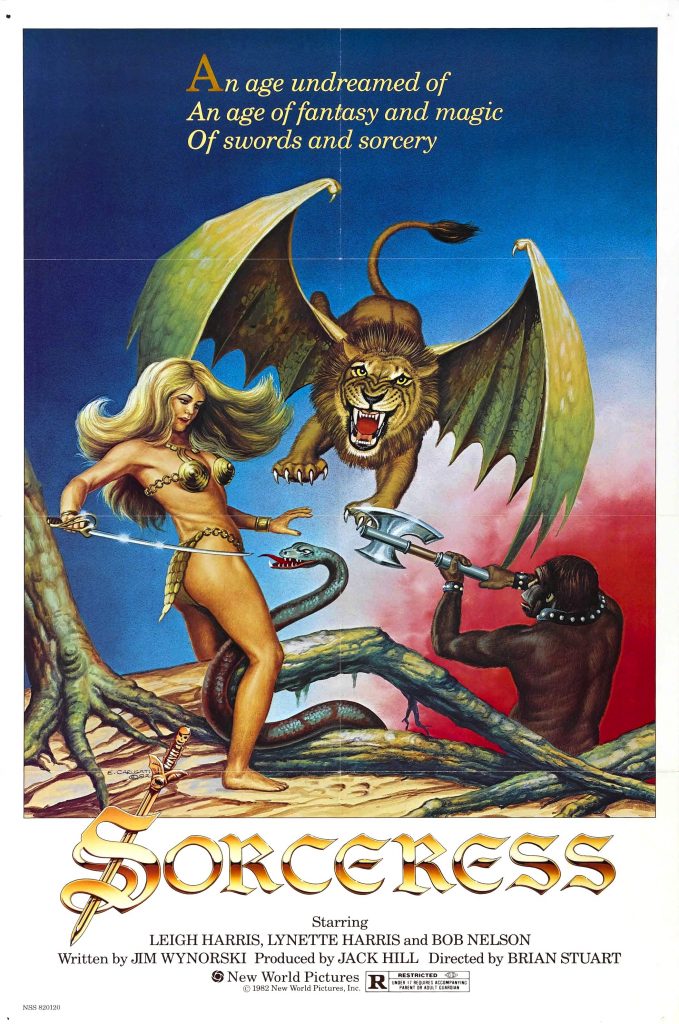

On the other hand, there’s my Prime Video feed (3). I tend to only watch Prime when on the exercise bike (riding an exercise bike is aerobically excellent but dull) and when I do I generally watch dumb action movies. My time in the saddle = my time to indulge in the shlock my wife won’t watch with me. As a result, Prime Video suggests an array of goofy-to-terrible movies, knowing only about my Prime behavior and nothing about my other interests or, dare I say, my rich background and inner life. No Prime, I am not interested in the 1982 film Sorceress, a poor man’s Conan the Barbarian(4). I went to graduate school!

These examples (5) show how music, film, and art of all sorts—collected under the umbrella of content, a useful if overly corporatized term—is increasingly picked for us instead of by us, based on our past activity. The examples now, in late capitalist 2020 America, are legion: from Netflix’s “we just added a series you might like” emails, to Amazon’s related items, to Facebook’s intrusive location-based and IP address-driven advertising practices. A great part of technology-driven late capitalism is when my wife and I are at home and I’ll Google something and then she’ll see a related ad for that thing on her Facebook feed mere moments later, privacy settings be damned. It’s fine. It’s corporate surveillance in pursuit of profit as a sort of embrace. It’s fine.

As I see it, the problem, aside from technology-assisted monetization, is calling so many disparate things content. Thinking of art, writing, film, and music by deceased and somewhat obscure master slide guitar Chicago bluesmen all as content reduces individual works’, well, content, to yet another thing to put in front of consumers. And the ubiquity of the term has served to lessen the impact of what it describes while reducing, to said content’s loss, the degree to which our language describes content’s content. In other words, calling everything that could be content content is akin to the old canard of saying one’s name out loud over and over until it begins to lose its meaning as your name and dissolves into a series of sounds. Kevin Kevin Kevin Kevin Kevin. Content content content content content content content.

Moreover, in addition to depersonalizing each piece and doing harm to the language, rendering all art content flattens or levels that art. Thinking of discrete works of human production as content—in competition with content of all sorts, many unlike one another but all united under the same content umbrella—allows content to be more easily categorized, sold, and judged. It helps us avoid surprises.

But don’t just take my word for it; the opening of Christian Lorentzen’s “Like this or Die,” on the fraught state of the book review, does a better job of showing than I can tell:

Alex and Wendy believe in the algorithm. It’s the force that organizes their feeds, arranges their queues, and tells them that if they liked this song, video, or book, they might like that one too. They never have to think about the algorithm, and their feeds offer a kind of protection. Alex hates to waste his time. His time is so precious. It makes Wendy feel sad when she reads a book she doesn’t love. She might have read one of the books her friends loved. If their feeds lead them astray, Alex and Wendy adjust them. There’s only so much time, and when they have kids, there’ll be even less time. Alex and Wendy aren’t snobs. They don’t need to be told what not to like. They’d rather not know about it.

***

Avoiding surprises—or more specifically shocks—is hardly surprising in this age of blasting trumpets (6), but it is, nonetheless, unfortunate. Sure, many of the surprises Americans have endured for the past few years have been unpleasant, but that doesn’t mean surprises are inherently bad. The larger point, which falls into the category of “hardly novel but it should be reiterated anyway, and often,” is that random human interaction—which the polis at its best facilitates, frequently using arts a social lubricant or communication tool or goad—is generally a good thing. My interaction with the rappers was yet another example of the way city life can lead to the unexpected.

And sure, to be fair, I was not into their music. But that doesn’t lessen the worth (at least potential worth) of the experience, because the list of times I’ve been exposed to new art either by accident or wholly organically is as long as my arm. A good one is how I came to hear Fela Kuti’s music for the first time, at the distressingly old age of 24 or 25 (my mid-twenties remain a blur) (7).

One Saturday, when I was living in Fort Greene, a friend and I walked down to the DanceAfrica street fair held every May at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. When we got there—amidst the New York street fair-standard scents of roasted corn—I heard what seemed like the best fucking music I’d ever heard in my life coming from one table. I practically ran over to the table in question and asked the guy manning it who we were listening to. In broken English, he said Fela something that I didn’t catch but I didn’t care; the dude then sold me an extremely bootleg CD titled “Fela #1” for five bucks.

Back home in my apartment, I put the CD on (which I now know was several of Fela’s singles cobbled together) and oh my god, “Zombie” came on. That afternoon so many years ago, brought to me by excellent weather but really by Fela Kuti, has stuck with me since. It was brought to me by surprise.

To close, here’s a scene from Jane Jacobs’s landmark 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, describing a similar encounter one night on her block of Hudson street in the West Village. Stuff like this is why we’re alive:

Deep in the night, I am almost unaware how many people are on the street unless something calls them together, like the bagpipe. Who the piper was and why he favored our street I have no idea. The bagpipe just skirled out in the February night, and as if it were a signal the random, dwindled movements of the sidewalk took on a direction. Swiftly, quietly, almost magically a little crowd was there, a crowd that evolved into a circle with a Highland fling inside it. The crowd could be seen on the shadowy sidewalk, the dancers could be seen, but the bagpiper himself was almost invisible because his bravura was all in his music. He was a very little man in a plain brown overcoat. When he finished and vanished, the dancers and watchers applauded, and applause came from the galleries too, half a dozen of the hundred windows on Hudson street. Then the windows closed, and the crowd dissolved into the random movements of the night street.

***

Header image and picture of Donovan McNabb via Wikimedia Commons. Sorceress image via IMDb.

(1) Insert jokes about how Seattle is not a real city here.

(2) Throughout, assume that “we” = at least semi-urban Americans living in 2020, with access to the internet and smartphones and all that.

(3) Yes, reader, I do seem to use a lot of these services even though they make me uncomfortable. Funny, that.

(4) Or for that matter, Beastmaster. Interestingly, all three movies were released in 1982, which was one hell of a year for gritty fantasy action.

(5) The first is admittedly positive, which I concede undermines the point I’m trying to make somewhat. And perhaps the success of #1 over #2 is due to algorithm excellence or catalog breadth but still: my argument stands.

(6) To cite the book of Revelations by way of Protomartyr, a post-punk band from Detroit I discovered via a review several years back. Protomartyr is now one of my very favorite bands. They rule.

(7) As a record snob, it pains me to relate just how long it took for me to get into Fela. I remain stunned and embarrassed in retrospect.