This essay was originally published in MQR 29:1, Spring 1990. The full issue is available in our archive

The recent furor surrounding the exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, canceled at the last moment by the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art under pressure from several conservative members of Congress, has highlighted the complex and contradictory relations of the art world to the host society in a dramatic way. No longer protected in the Reagan-Bush era by a dominant liberal consensus around values like freedom of expression, civil liberties, and equal opportunity for all, our cultural institutions and their custodians have been thrown into confusion and disarray by such a bare-knuckled political assault. Among those cheering the Corcoran’s capitulation is neoconservative art critic Hilton Kramer who forecasts a salutary return to the respect for family values and “decency” that publicly-funded art should uphold. In contrast, the trustees of the Whitney Museum, representing the liberal center that has long dominated the culture industry in the U.S., ran full-page ads in the New York Times and the Washington Post denouncing the “killing” of (pure, transcendent) Art by (impure, immanent) “politics.” To those on the left, who are rarely consulted by the media, it all seems like business as usual. What dissenting “artistic expressions” our corporate monopolies haven’t already suppressed or marginalized, the State will attend to.

What is novel is that despite the lingering popular perception of the art museum and gallery as timeless, pleasurable refuges from the rough-and-tumble of everyday life, the arts are becoming frankly identified as arenas of ideological contest. The abolition of the National Endowment for the Arts’ fellowships for art critics in 1984 was the opening salvo in a right-wing campaign to defund (and thereby dismantle) forums and opportunities for experimental, oppositional practices and discourses. Freedoms taken for granted merely a decade ago are now sharply under siege. The irreverent display of the U.S. flag as part of a student exhibition at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago last Spring (gentle stuff to those who remember the Days of Rage) provoked a firestorm of public criticism, demonstrations on the part of irate veterans, the withdrawal of public funds from the school, and its temporary closing while trustees rushed to publish full-page apologies in the local newspapers. Senator Jesse Helms’s legislative efforts to hamstring the National Endowment and ban public funding for what he deems “pornographic art” may not win full Congressional approval, but the damage has been done already. (1) As the Corcoran’s response demonstrated, grant administrators and museum curators will further censor themselves, and withdraw support for potentially controversial works, rather than risk financial loss and public harassment by the self-appointed watchdogs eager to bite.

From my own position as an artist, critic, and committed feminist teacher at an elite art school, it has become obvious that pedagogical concerns must extend beyond those of craft expertise and the conventionally subjective, hermetic, and self-reflexive discourse of the studio. Increasingly, class discussions have evolved into metadiscourses on the historical character of cultural institutions and their changing functions and how we, as mostly white, educated, cultural producers, position ourselves (and are positioned) within them at this particular historical moment. (2) The need to acknowledge and develop a mature working ethics, as well as an aesthetics, has become the focus of much of my concern in the classroom – a need that until very recently has been utterly and categorically denied in art education, and to which there is still considerable (largely passive) resistance.

My current interest in tracking contemporary cultural factors in the assignment of “artistic value” stems from a panel discussion at Ohio State University that was convened several years ago to debate a controversial exhibition of regional photography then on display at the school. (3) As a panelist, I was asked to address the specific issue of how this publicly-funded exhibition, selected by a blind jury comprising both sexes (though all four jurors were white), happened to have no women’s work nor work by any artists of color represented. Abjuring any notion of affirmative action where individual artistic talent is concerned, the jurors and administrators had refused to re-jury the submissions when it was learned that only work by white males had made the final cut. The resulting show was predictably homogeneous in its respect for well-established formalist styles of fine-art photography, showing indeed no transcendent commitment to “quality” as the jurors protested, but the shared aesthetic bias of the selected jurors who, one would speculate, found more politicized, polemical, content-intensive works (predominantly created by feminist and minority artists) of lesser “visual” worth. Asked to address the immediate question of how this local exhibition reproduced the status quo despite its organizers’ liberal intentions, I quickly found myself immersed in the larger questions of what social functions art education and the marketing, collecting, and exhibition of works of high art serve in our society and at what points an oppositional practice can insert itself into that nexus to any effect – or if this is even possible.

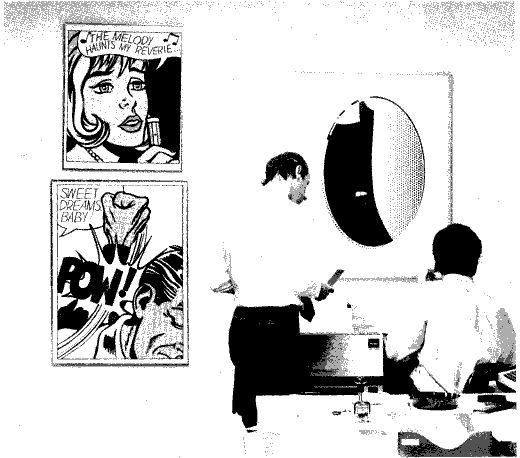

In a much-discussed essay originally published in the glossy monthly Art in America, conceptual artist and provocateur Hans Haacke warned art world readers that “museums are now on the slippery road to becoming public relations agents for the interests of big business and its ideological allies… [they] create a climate that supports prevailing distributions of power and capital and persuades the populace that the status quo is the natural and best order of things.” (4) At the time (1984), this seemed a bold assertion to those predisposed to believe in the objective scholarly commitment and nonpartisanship of major established art museums and their directors. However, since Haacke’s essay appeared (and, along with his art, it went far in calling our attention to the role of big business in the culture industry), the thickening commerce between corporate and high cultural institutions has become unabashedly obvious, even to the most dewy-eyed art student. Unlike previous cohorts of art-school graduates in the 1960s and ’70s, however, this state of affairs is increasingly acquiesced to-even embraced and exploited -by avatars of a new “business savvy” approach to artmaking and marketing, an approach more suggestive of Wall Street than the bohemian garret of bygone days. (5)

The market mentality that pervades all aspects of the art industry is actually the result of more than two decades of changes that have taken place at the very top, in the inner sanctums of museum boardrooms, as well as in the more public arenas of commercial galleries and auction houses. The trend accelerated in the late 1960s when Thomas P.F. (“Publicity Forever”) Hoving succeeded James J. Rorimer as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1967, the year of Hoving’s ascendancy, corporate contributions to the arts came to less than $30 million. In 1984, the Business Committee on the Arts estimated that total corporate support topped $600 million. If commissions and corporate collecting, together with a host of small in-kind donations are added in, the grand total of corporate funds flowing into the arts today is probably nudging the billion-a year mark.

Hoving was the controversial marketing genius and self-styled cultural populist who introduced the business community to a large, untapped middle-class market of potential art-consumers. He virtually invented the concept of “blockbuster exhibitions,” corporately financed shows designed both to draw on and create popular markets for the consumption of “high culture,” cultivated and groomed through sophisticated marketing techniques and popular education. The lure of these blockbusters, toward which all show-related advertising is directed, is the guaranteed blue-chip status of the “masterpieces” they purvey: a Caravaggio altarpiece, King Tut’s golden mask, a da Vinci drawing from the Vatican collections, a Renoir nude. Familiar icons from our college art survey texts, these objects are infused with the aura of their own ineffable “greatness,” and are proffered to be passively worshipped for their fame and rarity – not interrogated for the social contingencies of their value. (6)

Art-sponsoring corporations like tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris conduct surveys of public opinion to determine how better to capture the art-consuming market. In these surveys, art is discussed frankly like the commodity it is – a source of leisure entertainment designed to “deliver” consumers to corporate advertisers, competing with shopping malls, sports events, and television for the market share. Accessible, “family fun” entertainment is the watchword in boardrooms and executive offices. Critic Brian Wallis has drawn parallels between the museum of the late capitalist period and the department store of a century earlier:

Just as the department store initiated the middle-class consumer into the life-style capitalism at the beginning of the modernist period, so now the temporary exhibition welcomes visitors in droves to imbibe “culture” within a particularly restricted value system, rigorously crafted through the joint efforts of the museum and the corporate sponsor. (7) (my italics)

Needless to say, this constitutes a dramatic change in how museums consider their role in society. The public to be wooed through their portals is by no means general, but a public with money to spend. In addition to raising revenues, the hefty admissions fee to most major art museums serves the useful “security” function of keeping out the poor who might spoil the high tone of the decor and annoy middle-class visitors. Selling the “total museum experience” to target groups of consumers has become paramount.

In October 1988, 300 museum trustees convened at Walt Disney World in Orlando to discuss new marketing strategies for their institutions, including a session on “Creating Museum Magic Through Quality Service Disney Style.” As a journalist who covered the meeting for the New York Times noted,

Distinctions between museums and Disney have become increasingly blurred-the Metropolitan Museum of Art has replicated a Ming Dynasty Scholar’s Courtyard and Disney has built a half-scale replica of Beijing’s Temple of Heaven; the Smithsonian Institution has built an IMAX (giant-screen) theater, and Disney presents “quality art exhibitions.” No wonder museums are looking to Disney for new ways of dealing with audiences without boring them. (8)

Disney World’s “multi-experiential” approach appealed to museum administrators looking for ways to increase audience participation and attention span with a mixture of “entertainment, education, food and souvenirs.” New museum complexes are already being built along the lines of Disney’s Epcot Center: Parc de la Vilette in Paris spreads over 135 acres and comprises a science museum, a 360 -degree giant-screen theater, a concert hall, an exhibition hall, as well as music and theater centers.

Advanced communications technologies are seizing the imaginations of museum professionals as well. In the U.S., a consortium of museums, including the Metropolitan, the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art are exploring a joint computerized video data bank of their collections to make them more accessible to the public-perhaps on large-screen video terminals in museum “education centers.” In its latest survey of “Americans and the Arts,” Philip Morris touts the potential of the home videocassette recorder as a vehicle for bringing art to the public, noting that a “conservative assumption of 5.7 arts tapes bought or rented annually per interested VCR owner could put the value of the total market for arts videocassettes somewhere in the vicinity of $2 billion a year.” (9)

But even more than blockbuster exhibitions and technical razzledazzle, the auxiliary merchandising connected with these spectacles has come to generate significant profits. The market for museum replicas and show souvenirs has burgeoned phenomenally since the 1970s. Sales of official King Tut reproductions by the six-museum consortium that sponsored the exhibition totaled $17.4 million. The marketing of museum reproductions to middle-class consumers feeds a desire already whetted for collectibles. The “treasures” and “masterpieces” on display can now be had for affordable prices in one’s very own home. (10) In fact, approximately 40 percent of the Metropolitan Museum’s 1979 gross income came from merchandising and since 1981 net proceeds from its “auxiliary activities” (parking, auditorium rental, restaurant, catalogues, and merchandise), have grown seven-fold and now account for nearly ten percent of its total net income.

Where has this money gone? In the case of the trend-setting Metropolitan, these funds have gone into an elaborate expansion program initiated by Hoving and continued by his successor, Phillipe de Montebello. Since Hoving’s time, the Met’s operating budget has risen from $7 million to $63 million and its staff has more than doubled from 1,000 to 2,200. Beginning in 1968, with Hoving’s publicly-funded acquisition of the hellenistic Temple of Dendur, six new wings have opened, almost doubling the museum’s floor space, at a cost of over $200 million. In the words of one critic, “the museum has grown into a huge beast, and the job of its management is to feed the beast.” (11)

Like the opulent display of museum reproductions in mail-order catalogues, a growing tendency toward the amassing of precious objects in sheer abundance can be seen in museum exhibition design. The Metropolitan recently opened its new Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art where some nine thousand objects of American fine and decorative art (including 42 tankards, 50 teapots, 50 porringers, and 80 pressed-glass bowls and plates) are arrayed on shelves in 40 floor-to-ceiling glass showcases, covering 17,000 square feet of floor space. This “objects-by-the-square-foot” approach represents a revolutionary change from conventional displays of decorative arts where the objects are displayed in the reconstructed environment of the “period room.” The rejection of historical contextualization in favor of the celebration of the objects’ aura-inspiring presence was remarked upon by Luce Center curator Lewis I. Sharp. “The Met is not a historical society,” according to Sharp. “Now one can savor the visual pleasure of being overwhelmed by thousands of articles representing every aspect of the American experience without one more curator telling you why any one of them is beautiful.” (12) (my italics)

The American experience (and one is not encouraged to ask whose “American experience”) is reduced to its collectible material commodities. Five decades of modernist curatorship (led by the Museum of Modern Art) made indigenous folk crafts and selected “minor arts” marketable, and their possession denotes participation in a sophisticated lifestyle of “quality” and good taste. Indeed, the museum has come to have more in common with the luxury shopping mall than the public library or scholarly archive. Masscirculation decorating magazines, newspapers, and popular journals show how the wealthy live among rooms overflowing with fine and decorative art, arranged by professional interior decorators.

“That’s a Meyer Vaisman,” said Barbara Schwartz, off and running on a tour of the vast 4,000 square-foot loft she recently designed in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. “And that’s an Ashley Bickerton behind the Mies chaise and a Peter Halley on the far wall of the living room.” (13)

Conceptual artist Louise Lawler has offered a wry commentary on this phenomenon by photographing with deadpan earnestness the “arrangements” of objects in collectors’ homes and corporate spaces, as well as in museums. One typical Lawler caption reads: “Photographs by August Sander, one by Ansel Adams, sculpture by Robert Smithson, desk light by Ernesto Gismondi; arranged by Barbara and Eugene Schwartz.” The collectors (and/or their decorators) are given equal billing with the artists, acknowledging the social construction of the immediate material contexts in which these works are inserted and the socially-desired status with which they endow their owners.

That the fine arts museum functions to valorize the accumulation of wealth has been true since its origins. The 1980s, like the “Gilded Age” and the “Roaring Twenties,” witnessed a dramatic demographic bulge of overnight millionaires, not only in this country, but in Europe and Japan. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that there are currently 1.25 million millionaires in the U.S. (135,000 of

Louise Lawler, Arranged by Donald Marron, Susan Brundage, Cheryl Bishop at Paine Webber, 1989.

whom live in the greater New York area,) and 150 billionaires worldwide. Thorstein Veblen defined the purpose of conspicuous consumption as the ability of a person “to sustain large pecuniary damage without impairing his superior opulence.”(14) Art objects have always been highly prized by collectors because they are not functional, but very expensive, and thus provide opportunities for “pure”‘ acts of “pecuniary damage.” The recent giddy scene of skyrocketing prices on the art auction market has conveniently served class interests in keeping this most expensive sport a highly exclusive one. “As soon as people have money today they start collecting,” observed one New York dealer. “Art comes right after the mink and the Mercedes.”

The burgeoning international demand for rare, expensive art has fueled the auction market and last year alone saw records tumble in all departments, from Old Masters to antiquities to folk art. Museums themselves have been driven out of the market by prices only corporations or individuals can afford, causing much moaning and gnashing of teeth in curatorial departments. Art has become pure investment, often reappearing at auction within a year or two of purchase. More than ever, museums are forced to woo collectors and cater to their demands for status gratification. Again, Hoving was the exemplary pioneer in collector-catering in 1969 when he agreed to trustee Robert Lehman’s death-bed request that an entirely new wing be added to the Metropolitan to house his collection of Old Masters intact. (15)

The new tax laws have further harmed donations to museums by only allowing donors to deduct the purchase price of their gifts, not the appreciated value. The immediate effect has been a drop of about 50 percent in gifts of art valued at more than $25,000. At the Art Institute of Chicago, the total of donated art plunged from 3,000 gifts in fiscal 1987 to 755 gifts in 1988. “People can have the best will in the world,” said one museum director, “but when they sit down with their accountants, they can be dissuaded.” (16) Some collectors have retrieved works on loan to museums and placed them at auction. Recently, a Jacopo Pontormo portrait of Duke Cosimo I de Medici that had hung at the Frick Museum for nearly two decades was auctioned off for its owner by Christie’s. The Getty Museum in Malibu, perhaps the only museum endowed sufficiently to play in the big leagues, bought the work. A Rembrandt that had been on loan to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts was sold at Sotheby’s to a private investor who removed it from public view. (17)

To retain the interest of those on whose generosity they depend, museums have established exclusive “perks” for patrons which gratify the need for instant social status among the newest mega-rich who crave contact with the beau monde of artists, pop stars and fashion. The Metropolitan Museum now offers its spacious galleries as the latest chic venue for private parties. For a mere $30,000, the Hall of Dendur or one of the other grand salons can be rented for a birthday bash, bar mitzvah, wedding reception, or company cocktail party. Neoconservative critic Hilton Kramer has fussily decried the rudeness and messiness of these sacrileges in the temple, where champagne is frequently spilled and more than one careless elbow has been known to knock into some priceless marble statue. The late Diana Vreeland, a Hoving hire, made the Metropolitan Costume Institute’s annual dinner one of the most sought-after invitations on the Fall social circuit. There, the corporate crowd could mingle with the fashion crowd among the treasures and masterpieces.

The Metropolitan also provides a progressive ladder of status signifiers for its donors, ranging from access to the Patron’s Lounge ($3500) to a seat on the Chairman’s Council ($30,000) to Benefactor ($400,000) where you get your name carved on the museum’s travertine wall. The most coveted social cachet is an invitation to join the Met’s Board which cost each of its most recent members, Henry Kravis, Larry Tisch, and Milton Petrie, a cool $10 million. All of the biggest collectors sit on museum boards. Because their money is so necessary to “feed the beast,” they tend to ask, as art-journalist Grace Glueck put it, paraphrasing John F. Kennedy, not “what they can do for the museum, but what the museum can do for them.” (18)

For trustees from the corporate world, the quid pro quo is the opportunity to polish the company image. This is most egregiously visible at the Whitney Museum where satellite museum outposts occupy the corporate office buildings of Philip Morris, Equitable Life, Champion International, and IBM. Equitable vice-chairman Benjamin Holloway unabashedly disclosed his company’s motives in setting up a Whitney satellite: “This is an investment property for Equitable, there’s no question about that. We are doing these things because we think it will attract and hold tenants, and that they will pay us rents that we’re looking for.” (19) Like the Metropolitan, the Whitney is expanding its real estate ambitions, adding a new building designed by Michael Graves that will more than double the exhibition area. Its trustees are sought from among the high rollers in the acquisitions-and-mergers field, investment bankers, and real estate developers. No minorities are represented on the board and there is only one woman, board chair Flora Miller Biddle, granddaughter of founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

The museums’ administrative bureaucracies increasingly conform to corporate standards and ethics in their decision-making and goals for the institutions they oversee. One mark of this is the sharp division between administrators and curatorial staff, with the latter increasingly subordinated to the former. At the Met, where executive offices now fill space set aside for the conservation department, one staffer told a reporter, “curators used to see themselves as the core; now they see themselves as the periphery.” (20) A museum director’s social connections and fundraising skills are clearly as important, if not more important, than a record of published scholarly monographs.

Because museums must compete for a relatively small number of eligible board members, each must distinguish itself from the pack and emphasize qualities that make it attractive to potential corporate patrons. The Whitney, for example, has nurtured its image as a youthful, daring and risk-taking institution. Trustee and shopping mall developer Alfred Taubman bragged, “It’s probably the most energetic and least safe of the New York museums when it comes to dealing with issues relating to contemporary art.” (21) This image has made the Whitney attractive to corporate C.E.O.s who wish to be seen as risk-takers and energetic, innovative leaders. Recalling how he became involved with the Whitney in the early 1960s, former Philip Morris head George Weissman recalled,

For $5000, we became their first corporate sponsor. At that time, [architect Ulrich] Franzen was redoing our offices, and on our executive floor we wanted to create an environment… that told our people, “We’re not afraid of new ideas.” We wanted to go the route of American art since tobacco was so American. And the Whitney was the place rather than MoMA or the Met. (22)

Corporations like to be associated with abstract ideals like Freedom, Creativity, and Quality and think of themselves as the underwriters and protectors of these pillars of western liberalism. Business executives don’t hesitate to compare their patronage to that of the Medici, an image that museum administrators and many culture industry boosters are quick to flatter. (23)

But some business connections in museum boardrooms have tested another liberal ideal where markets are concerned: freedom from conflicts of interest. Whitney trustees Taubman and Leslie Wexner acquired Sotheby’s auction house in 1983 with a consortium of partners. Although no charges of market manipulation have been made, the potential is great. The Whitney has been excoriated in the art critical press for its pandering to celebrity (like the recent Yoko Ono show) at the expense of more thoroughly researched and historicallyminded curating. Often the lines between the Whitney’s shows and commercial gallery displays have become quite blurred. Times critic Michael Brenson characterizes its flagship exhibition, the Whitney Biennial, as “a contentious rambling salon that embraces the idea of the new in a more or less unquestioning way.”

By concentrating on the most visible art, the Whitney reinforces the late modernist notion of an orthodox mainstream taste, in the process reinforcing the power of the dealers who sell it and the collectors who buy it. (24)

While Brenson lays partial blame for the rampant “fadism” of the 1980s on this blurring of boundaries between the museum and corporate worlds at the very top echelons of power, he also implicates a new generation of curators at the lower “management” levelsaggressive, young, street-smart promoters – with few qualms about the manipulation of artistic production for immediate commercial profit. Like the Reagan-era market-savvy artist, any vestigial ideals concerning the separation of art and commerce are jettisoned. In this cynical market climate, artist (and former commodities broker) Jeff Koons gleefully fabricates kitschy painted porcelain statuettes of pop-singer Michael Jackson and Buster Keaton and sells them at fancy galleries for outrageous prices ($50,000 to $150,000) to hungry collectors.

Rather than museums, which require established academic and social credentials (and at least subscribe to the appearance of an authoritative impartiality), commercial galleries have become the venues of choice for these freelance curators, many of whom began as artists and critics involved in Manhattan’s East Village art scene in the early 1980s. Curatorial team Tricia Collins and Richard Milazzo recently put together an exhibition for the Stux Gallery in Soho which demonstrated the new sorts of relationships that have formed among dealers, curatorial “experts,” and collectors in an atmosphere of volatile and lucrative markets for contemporary art. Titled “Pre/Pop -Post/Appropriation,” Collins and Milazzo juxtaposed works by blue-chip market stars Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns with works by young artists like Meg Webster and the Starn Twins who are hot commodities in the Stux stable. Purporting to show an important stylistic affinity between Pop Art of the 1960s and these contemporary figurative works, and bolstered by a glossy (dealer-financed) catalogue, the show was a thinly disguised marketing ploy to enhance the value of dealer Stefan Stux’s properties.

These freelance curators have eagerly courted collectors and dealers who are too busy to look at work and are only too happy to let “experts” do the winnowing for them. “Tricia and Richard have been instrumental in helping me build a collection basically from scratch,” says financier Howard Johnson 3rd. “They introduced me to artists and to galleries, and helped me get work which is extremely hard to get in some cases – especially when an artist has a good following.” (25) Some curators work for a flat fee while others, like Collins and Milazzo, take a direct cut from gallery sales. That art critics have always promoted the work of the artists they like (it could be argued that this is part of their job) and exchanged their influence for gifts and other favors (more ethically questionable) is nothing new. Influential art critic Clement Greenberg was a most notorious wheeler and dealer, assembling a sizeable collection of works by his proteges and freely taking commissions from particular galleries with which he was associated.

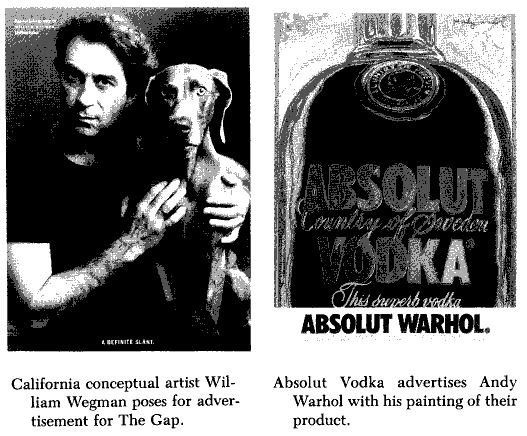

But what is new in the 1980s is the hyping of artists as celebrities in the mass media, where advertisers and fashion directors have cashed in on the commodifiable mystique surrounding artists, using them (both the known and the obscure) to hawk fashions and luxury products. The Gap has William Wegman sporting its T-shirts; Barneys of New York has Edward Ruscha nattily attired in a Redaelli suit. Artists Cindy Sherman, the Starn Twins, Jeff Koons and Annette Lemieux model fashions for Vogue. Laurie Anderson sells American Express. Andy Warhol sells vodka. Better than any other class, artists can sell the romantic image of ultimate creative freedom and individualism so enviable to an affluent class of educated, white, middle-class consumers (the target of much brand-name advertising) whose real choices are highly regulated in our economy. In the words of social critic and art historian Carol Duncan, “.. the modern artist is a combination of the ascetic saint and the virile, daring folk hero. His unconventional art bears witness to both his heroic renunciation of the world and his manly opposition to it. In appreciating those qualities, viewers can live them vicariously.” (26) And of course there is the spin-off effect of the “art aura:” successful Washington, D.C. art dealer Max Protetch shares his “rare character” with J&B Scotch. A new breed of publicity-seeking collectors (the Saatchis come to mind) have used their artworld wheeling and dealing to reinforce an image of dashing derring-do in the business world – conquerors of all markets.

In an artworld so clearly molded and regulated to serve the needs of the dominant and most privileged sectors of our society and their ways of doing business-the same sectors which benefit from the perpetuation of major conflicts of national, class, race and gender interests-what are the possibilities for oppositional, critical practices to assert themselves and be received? As the history of art amply demonstrates, high art production has always served the status quo; those in power always get the cultural products and producers they need and make every effort to police the flow of ideas to uphold their power. But the system is not monolithic and ruptures and fissures appear which can be exploited by those who are adequately equipped, committed, and ready. Carefully prepared strategies are required.

First of all, even though as art-makers and consumers we are taught to embrace the romantic image of the artist as a lonely individual genius who conquers history, it is clear that artists (and cultural workers) can do little by themselves to challenge the entrenched status quo. But too often, this practical observation has

become a conveniently self-fulfilling and self-defeating excuse for discouraging innovative thinking about what it is that artists can do collectively. Even in art school, the identification of shared group interests among artist-teachers and artist-students is thwarted by the traditional pedagogy.

The conventional art-school critique pits individual students against each other in intimidating public performances before the teacher. Those able to assert themselves most forcefully are reinforced for these overt signs of personal “integrity” and “commitment.” However, as has been amply demonstrated (and much discussed among feminist and minority caucuses within professional art organizations), this competitive atmosphere works against women and minority groups (e.g., gays and lesbians, racial minorities) who are afraid to assert their different viewpoints in public for well grounded fear of provoking ridicule, trivialization, or worse. Nonetheless, many teachers continue to view the competitive critique as a necessary proving ground for the highly-selective “real world” of museums and galleries – never questioning its larger ideological usefulness in discouraging any nascent consciousness of collective identities or interests. (27)

It also seems clear that critical practices must respond to historically-specific contexts, whether or not the work has any ideological currency beyond the immediate occasion of its making or the specific audience for whom it is intended. Haacke, the acknowledged master of strategic intervention within the high art world, chooses his targets with great care, often spending months researching the material details for his works. Not preoccupied with idealistic notions of making art for the ages, Haacke and others like him engage the most mundane historical facts, naming names, and ruthlessly exposing the duplicity and contradictions of the ruling elite’s use/abuse of high culture.

A good example of Haacke’s approach can be seen in a work like U.S. Isolation Box, Grenada (1983), which was first exhibited at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York shortly after President Reagan sent the U.S. Marines to topple Grenada’s socialist government. Following a news account of U.S. troops’ use of eightby-eight-foot isolation boxes to detain Grenadian prisoners, Haacke reconstructed an isolation box to scale out of planks. On the side was stenciled in large letters, “ISOLATION BOX AS USED BY U.S. TROOPS AT POINT SALINES PRISON CAMP IN GRENADA.”

While the stark, geometric presence of the box recalled minimalist art, any attempts at such aestheticized readings were immediately undercut by Haacke’s labeling of the box’s undeniably barbaric function. The presence of the work in a publicly-funded art show provoked an uproar in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal and the CUNY Graduate Center tried to remove it from view. But Haacke, agile and always ready to respond to such ad hoc maneuvers, used the attempted censorship to further reveal the politicized nature of the artworld and the hypocrisy of our culture’s liberal democratic commitments to free speech and the right to dissent.

In the past, the liberal marketplace has permitted a small strategic space to exist for Haacke and a few others who have been ready to exploit its contradictions, though this may disappear in our current climate of reaction, and none realizes this better than Haacke himself. With the removal of federal support for controversial or critical art (whether directly, through an act of Congress, or indirectly, through institutional self-censorship), the projects of lesser known and minority-group artists unable to attract private funding will not be able to be produced at all. And publicly-supported institutions, fearful for their funding, will not be inclined to show it anyway.

But even as the current Supreme Court’s regressive stance on civil rights and women’s rights to reproductive choice has produced a resurgence of grassroots activism, it can be hoped that the bigotry and mean-spiritedness of the proposed Helms amendment and its attendant demagogueries will galvanize a new collective activism among artists, curators, critics, and other workers in the culture industry who are less afraid of the immediate damage to private careers than the threat to the right to make and exhibit their art at all. The National Endowment for the Arts was created during Lyndon Johnson’s domestically liberal democratic administration, an administration that produced most of the civil rights legislation that currently is being dismantled by the conservative majority of the Supreme Court. The legislative moves against the Endowment are part of a massive political attack on this two-decade legacy of social reform and expanded civil liberties, and must be seen as ideological turf battle over who shall decide which groups have rights and arbitrate what is permissible as cultural expression(s) in our society. Concerning the latter, Jesse Helms’s list is very, very short. But liberals cannot profess shock and surprise at the nature and severity of the right wing’s agenda, for it has been very much out in the open for the past eight years.

Several models do exist, however, for the kind of theorized art practice that is needed both to challenge the hegemony of liberal corporate values in the artworld and to call the conservatives’ bluff by (proudly) claiming its own political voice and the moral right for that voice to be heard in a democratic society. Not surprisingly, these are collective efforts, not just the work of isolated individuals. The Guerrilla Girls is a group of anonymous feminist artists who banded together in New York in the mid 1980s as “the conscience of the artworld.” Using posters, performances, and publications, the Guerrilla Girls publicly call attention to the continued discrimination against women by established art institutions and galleries. Dressed in gorilla costumes to disguise their identities and thus deny the celebrity-value of their actions, the Guerrilla Girls invade art museum openings, panel discussions, and other public events, disrupting the proceedings with loud recitations of damning statistics on the underrepresentation of women by the offending parties. With pointed irony, their posters (which are prominently plastered in the gallery district) reveal the continuing overt and covert sexism of the art world and the chilling effect it can have on women artists’ careers. Among “The Advantages of Being A Woman Artist” (1987), for example, the Guerrilla Girls list: “Having the opportunity to choose between a career and motherhood”; “Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty”; “Not being stuck in a tenured teaching position”; “Not having to undergo the embarrassment of being called a genius”; and “Seeing your ideas live on in the work of others.” Expanding beyond its initial New York base, chapters of Guerrilla Girls have formed in many communities nationwide and their activities are widely known.

Another effective strategic intervention was mounted in San Diego by a collective of three artists working under the auspices of the Centro Culturale de la Raza, a progressive, Mexican-American arts center in this bi-cultural city. In an effort to publicize the plight of Mexican workers during the 1988 Superbowl festivities in San Diego, the artists contracted with the municipal transit system to run a series of “art” posters on city buses. The words “Welcome to America’s Finest Tourist Plantation” appeared in red type over photographs of Mexican immigrant laborers montaged with a picture of (brown) hands being cuffed by the police. The posters caused a public furor, provoking lively debates for weeks on local television news and in the newspapers about the limits of free speech, public art and its funding, civic values, and even about the problems of Mexican workers. Not surprisingly, the city voted to ban such “political” messages from city buses in the future. The artists have since moved on to billboards, which are privately owned.

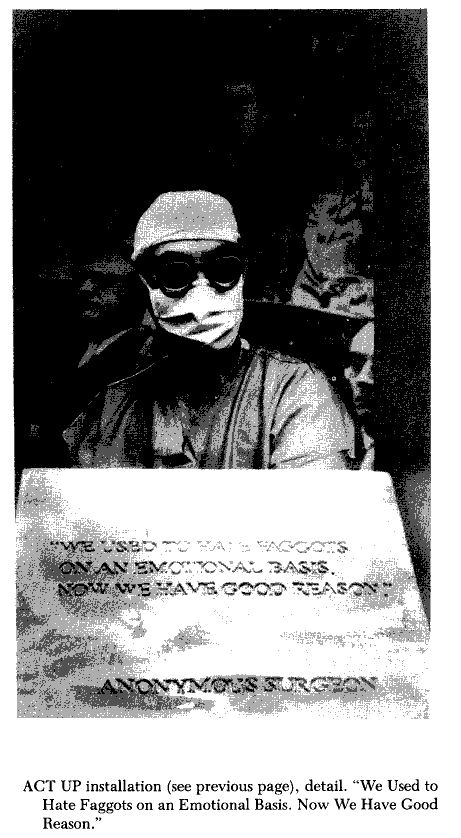

A third and final example of yet another marginalized group that has used its critical practices effectively to counter mainstream messages can be seen in the highly visible outpouring of action and artistic production in response to AIDS – a scourge that has hit the artistic community particularly hard with the loss of a number of bright talents at the pinnacle of their powers, including Robert Mapplethorpe. Much of this work is grounded in a politics of direct action that borrowed many of its strategies from left (Situationist) agit-art of the 1960s and its political theory from feminism. (28)

A recent comprehensive exhibition, AIDS: The Artists’ Response, presented a wide-ranging panoply of works by several hundred artists

responding to the social and medical crises of AIDS, including paintings, photographs, installation works, performance art, slideworks, graphic design, sculpture, films, and videotapes. (29) A whole gamut of (frequently contradictory) issues around the cultural and private meanings of the epidemic was explored in these heterogeneous works, including censorship, political indifference, safer-sex education, the channeling of information, homophobia, racism, the reclamation of taboo sexualities, pride, suffering, loss, memory, shame, the social interplay of medical misinformation, sexual oppression, and public fear. But the thread that wove these various themes together was the repeatedly expressed necessity for confrontation, for seizing control of the public meanings around AIDS, for fighting back. The inside back cover of the exhibition catalogue was given over to a simple three-letter graphic: “WAR.”

But as New York’s ACT-UP- affiliated collective Gran Fury reminded viewers on another starkly-printed page-spread, “WITH 47,524 DEAD, ART IS NOT ENOUGH.” As artists, teachers of,artists, students of art,, art consumers, art promoters, and art critics, we must learn to see and think about our practices and their implications within a much larger social context than has been traditionally the case in our modern, corporate-run social democracies. In this one sense, the right wingers are more honest than most of the liberal cultural establishment: they recognize that the art-cultural marketplace is (and always has been) a charged and politicized field. But in a diverse, democratic society – as opposed to the autocratic and totalitarian societies that crowd the pages of our art history books -our most urgent task is to cherish and fight for the liberating and humane possibilities that such a recognition allows. As mass information and the propagation of public values become increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few whom the current commerce of art serves so well, perhaps artists can be persuaded to reclaim a role that is as rightfully and. historically theirs as any other: that of critical, moral voices within their immediate social communities, making visible (with the tools they so competently wield) what is hidden by the dazzling glare of the marketplace.

Notes

(1) On July 26, 1989, the Senate approved by a voice vote measures proposed by Senator Helms to bar Federal arts funding from being used to “promote, disseminate or produce obscene or indecent materials, including but not limited to depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts; or material which denigrates the objects or beliefs of the adherents of a particular religion or nonreligion.” The House voted a punitive $45,000 cut from the Endowment’s annual budget – the amount that had been granted to fund the exhibitions of work by Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano which Helms and other conservatives deemed obscene. In addition, the Senate voted to cut the amount the Endowment could grant for support of visual arts by $400,000.

(2) Articles and projects that have been particularly useful in my thinking on these issues include Griselda Pollock, “Art, Art School, Culture,” exposure, 24:3, (1986); Jan Zita Grover, “The Subject of Photography in the Academy,” Screen, (Sept/Oct 1986); Simon Watney, “Photography – Education – Theory,” Screen, (Jan/Feb 1984); Martha Rosler, “Photography Meets the Art World, Professional Rationalization, Academic Marginalization, Quality of Life, and the Economic Crisis, exposure, 18:3,4 (1980); and Allan Sekula, “School Is A Factory,” in Photography Against The Grain, (Halifax: NSCAD Press), 1984. Also see my “Confusing my students, eating my words,” exposure, 26:2/3, (1988).

(3) The exhibition in question was Latent Images: Ten Midwestern Photographers (1986). The ten photographers were the recipients of a 1985 Arts Midwest/National Endowment for the Arts Regional Photography Fellowship. The NEA-funded exhibition of their work traveled to various museums and galleries throughout the midwest.

(4) Hans Haacke, “Museums, Managers of Consciousness,” Art in America, February 1984, p. 9.

(5) For a more comprehensive analysis of corporate uses of the myth of the avantgarde, see Richard Bolton, “Enlightened Self-interest: The Avant-Garde in the ’80s,” Afterimage, February 1989, p. 12. Also see Mary Jane Jacobs’s introductory essay to A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989):. for artists in the 1980s, the goal is to have secured a gallery by the time of graduation… Artists and their dealers strategize about obtaining important collectors for their work.”

(6) In this regard, one recalls marxist critic Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.” See “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), p. 256.

(7) Brian Wallis, “The Art of Big Business,” Art In America, June 1986, p. 28.

(8) Allon Schoener, “Can Museums Learn From Mickey and Friends?” The New York Times, October 30, 1988.

(9) Philip Morris Companies Inc., Americans And The Arts: Highlights from a nationwide survey of public opinion (New York: American Council for the Arts, 1988. Interestingly, the pollsters noted that cable television is not a good potential investment because “cable audiences tend to be less educated and less arts-oriented than VCR owners.” (p. 23)

(10) In direct reference to the usual fare of blockbusters, art critic Robert Hughes has quipped that the way to distinguish “treasures” from “masterpieces” is that treasures have gold in them.

(11) John Taylor, “Party Palace,” New York, January 9, 1989.

(12) Paula Deitz, “At the Met, 9,000 Objects in 40 Straight Lines,” The New York Times, December 11, 1988.

(13) Suzanne Slesin, “Where Contemporary Art Is The Decor,” The New York Times, February 2, 1989.

(14) John Taylor, op cit.

(15) As one of the collector’s friends put it to a journalist at the time, “Bobby Lehman wanted his pyramid, with plate glass before the artworks. See, Bobby knew about Macy’s: the entrance is small, but the display windows are large… When you go to Macy’s, the pots and pans are in the basement and the Lanvin perfume is at the entrance. Art today is a kind of cultural cosmetic.” See Sophy Burnham, The Art Crowd (New York: David McKay Co., Inc., 1973), p. 172. Burnham’s book is a deliciously gossipy and irreverent account of the machinations of the New York art world in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

(16) Suzanne Muchnic, “A Taxing Matter,” The Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1988. Also, see Grace Glueck, “The Mania of Art Auctions: Problems as Well as Profits,” The New York Times, November 26, 1988; “Donations of Art Fall Sharply After Changes in the Tax Code,” The New York Times, May 7, 1989; and Robert Taylor, “The costly quest for contemporary art,” Boston Globe, February 12, 1989. The entire July 1988 issue of Art In America and the November 1988 issue of ARTnews were given over to extended thematic discussions of the state of the art commodities market.

(17) See Michael Kimmelman, “The Case of the Vanishing Art,” The New York Times, May 14, 1989.

(18) Grace Glueck, “Mogul Power at the Whitney,” The New York Times Magazine (The Business World), December 4, 1988, p. 26.

(19) Ibid., p. 72.

(20) Taylor, op. cit.

(21) Glueck, op. cit., p. 75.

(22) Ibid., p. 76.

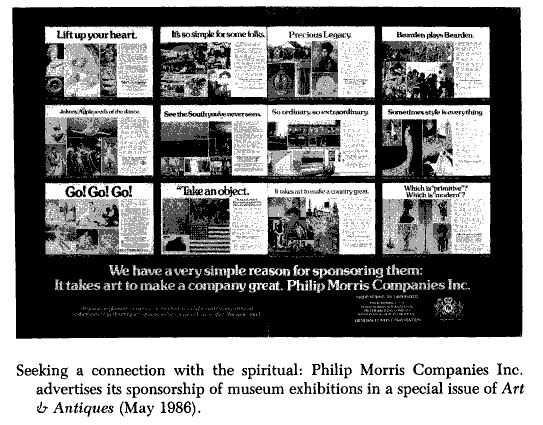

(23) The entire May 1986 issue of the glossy Art And Antiques was designed as a lavish “salute to the modern Medicis: the top corporate art patrons in America.”

(24) Michael Brenson, “The Whitney Today: Fashionable to a Fault,” The New York Times, January 1, 1989.

(25) Max Alexander, “Now on View, New Work by Freelance Curators,” The New York Times, February 19, 1989.

(26) Carol Duncan, “Who Rules the Art World?” Socialist Review (1983), p. 110.

(27) For further reading on the politics of the art studio/classroom, see Griselda Pollock, op. cit.

(28) See Douglas Crimp, ed., AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, (Cambridge: MIT Press), 1988.

(29) Jan Zita Grover, Lynette Molnar, guest curators, AIDS: The Artists’ Response, (Columbus: The Ohio State University), 1989.