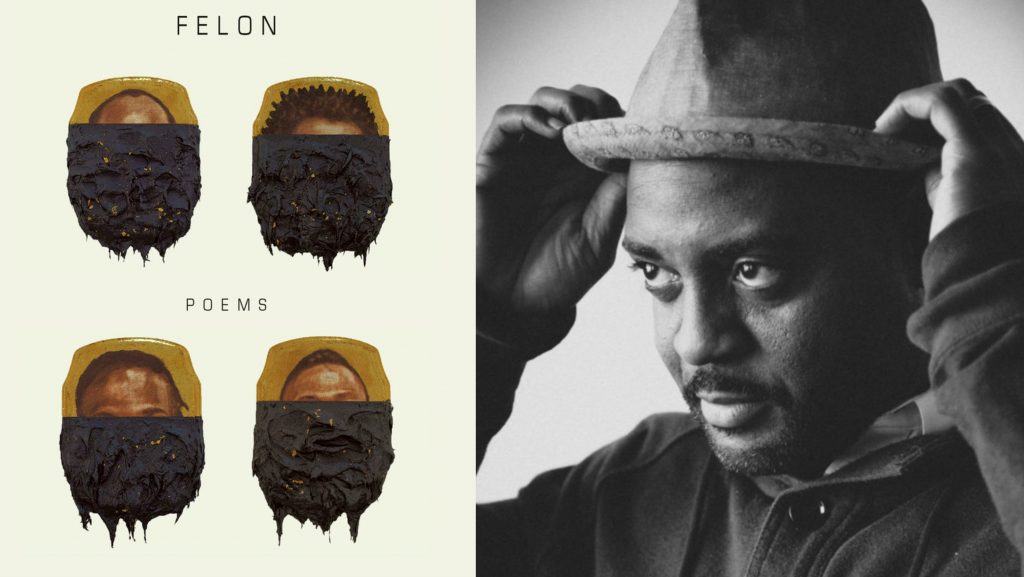

Reginald Dwayne Betts’ newest poetry collection Felon (W.W. Norton, 2019) details a lyric account of the butterfly effects of incarceration, specifically the mass incarceration of black men in the United States of America. In Felon, Betts builds on his two previous collections Shahid Reads His Own Palm (Alice James, 2010) and Bastards of the Reagan Era (Four Way Books, 2015), and draws on Betts’ own trek from incarceration as a teenager in maximum security prison to Yale Law School. Through a deft and complex twining of received forms with necessary current social content, Betts rehearses the ways in which being a felon has no time limit and extends far beyond the carceral spaces of jails and prisons.

Why insist on the word felon as the title to the collection? Perhaps someone interested in not foregrounding a man’s incarceration as central to his identity would use a phrase such as “formerly incarcerated person.” However, Betts chose to do exactly the opposite and foreground the word felon. According to the usage note in Random House’s Dictionary, the word felon carries within it an inescapable afterlife of a shame-based identity, an identity that carries on after the site of the crime or the incarceration’s duration:

Once a person is no longer engaged in crime we can say “He’s a former criminal.” And once a person is no longer incarcerated, we can say “She’s an ex-convict.” Though both statements carry a stigma, they leave open the possibility that the people in question have changed their behavior. But this does not seem to be the case with the term felon, which appears to have no time limit. Once a person has been convicted of a felony, he or she can be considered a felon for life, according to the strict meaning of the word. The term ex-felon, for example, is rarely used. Advocates for the reform of our criminal justice system point out that this usage makes it even harder for rehabilitated former criminals to reintegrate into society and thereby turn away from a life of crime.

Take, for instance, the opening poem of Felon, “Ghazal.” In the ghazal, a received form from Arabic verse, there is no room for guesswork as to the constraints of this poem. In any ghazal, each couplet ends on the same word or phrase (the radif), and is preceded by the couplet’s rhyming word (the qafia, which appears twice in the first couplet). The last couplet includes a proper name, often of the poet’s own name. The formal constraint of any ghazal locks each line into its eventual ending, the radif, which in Betts’ “Ghazal” is the word “prison.”

Name a song that tells a man what to expect after prison;

Explains Occam’s razor: you’re still a suspect after prison.

The repetition of the prison radif is mimetic of the constant psychological constraint of being a felon. After the first instance of the radif, no matter where the sentence or phrase starts, the radif will return; the prison will continue to enclose the mind long after the prison no longer encloses the physical body.

In the last couplet, the one which usually includes the poet’s name, instead of the name “Reginald,” the name “Shahid” appears.

You have come so far, Beloved, & for what, another song?

Then sing. Shahid you’re loved, not shipwrecked after prison.

While in prison, Betts was re-Christened Shahid, a name which, Betts has explained, means witness. The enclosed form of “Ghazal” indicates how the enclosure of prison extends into the mind of a felon well past the limit of the sentence. Think of the double meaning of that word: sentence. And yet, there seems to be a hope for love that extends from the “song,” or, one may say, the poem, the song Shahid may sing in the “after prison.”

In another lyric poem “Confession,” Betts subverts the common site of confession in the criminal justice system. Instead, the confession is expressed to the speaker’s “woman”:

If I told her how often I thought

Of prison she would walk out

Of the door

The poem begins with the suspended subjunctive “if” that is then repeated towards the end, drawing the poem to its ending:

…If I told my woman that, she

Would want to know if I thought

I deserved all that lost. Her mother

Wonders why I won’t let it go & hold

On to the happiness in this life we

Have. But how do I explain that outside

On nights like this, is where I first

Learned just how violent I might be?

That, I think of prison because in all

These years I still can’t pronounce

The name of my victim.

Again, the way a felon may relate to his loved one and the “nights like this” will continue to exist in “thought” even when he is not in prison. The victim still exists, and the guilt that renders the name of him unpronouncable.

And yet, in a collection that explores how the psychological half-life of incarceration for a black man in America, shimmers of hope glint in the baffling ineffability of life.

Take, for instance, the poem “November 5, 1980,” which begins with a heavy, mascuiline monosyllabic rhyming couplet of “slabs” and “tabs.”

I have called, in my wasted youth, the concrete slabs

Of prison home. Awakened to guard keeping tabs

On my breath. Bartered with every kind of madness,

The state’s mandatory minimum & my own callus.

The salient masculine rhyme pattern continues until the middle turn, perhaps a volta, where the rhyme scheme ceases to exist:

Under the water, rattling broke the silence. I cussed

Men with fists like hambones & got beaten to dust.

Buried memories in my gut that would fill a book.

I’ve carried pistols but have never held a bullet.

Instead of the rhyming couplet, the words “book” and “bullet” are paired together through the break in pattern. That break in such a dominant rhyme scheme jars attention and accrues dissonance on to that word “bullet.” Following, the poems then pairs “fear” and “hollow,” “so-and-so” and “troubled,” and the hanging word, without its pair: “baffle.”

But what of it matters, in this life so much has troubled,

& the few things that didn’t, never failed to baffle.

The unrhymed pairs comment on one another because of the rhyming couplet scheme that was altered at the volta. A book and a bullet. A hollow fear. A troubled so-and-so. These phrases are assembled through the poetic form. And yet, the bafflement, those things that did not trouble, does hope reside there? Is it a state of astonishment, of ineffability, of humility in the face of what haunts us?

Felon ends in another received form, a sonnet crown titled, “House of Unending,” again indicating how the idea of an “end” to incarceration, to suffering, to contemplation, does not exist in this collection. Sonnet crowns are a series of sonnets in which the last line of the previous sonnet becomes the first line of the next sonnet. The sonnet crown, in ways similar to the ghazal that opens the collection, is a formal enclosure that repeats as it unfurls. Again, the poem reads as though it is a ruminative catalogue, a hall of mirrors that the mind may never escape.

And while the brilliant lyric poems begin to express the sort of psychic imprisonment at the individual level, what is perhaps most notable in Felon is the series of four redaction poems that are interspersed throughout the collection. Betts’ redaction poems center on the systemic injustice of the money bail system. In the end notes, Betts writes that these poems “use redaction, not as a tool to obfuscate, but as a technique that reveals the tragedy, drama, and injustice of a system that makes people simply a reflection of their bank accounts.” Erasure is used as a tool to bring out the humanity of those people who are affected by the money bail system. What is erased is the legalese that treats human beings as if they were other than human, as if they were mere descriptions in a court document.

In ways similar to Solmaz Sharif’s 2016 collection Look: Poems, the poetic form of redaction and erasure becomes a tool to reveal injustice. The poems subvert how the government uses redaction to control what the public sees. The texts are erasing “official” language of the US government, whether military or carceral, and how that “official” language erases black and brown people impacted by the state.

To exhume these human beings buried by the money bail system, the typeface of the collection was also commissioned specifically for Felon. The note “On the Type” at the end of the collection states:

The title pages, page numbers, and redacted poems are typeset in Redaction, a new font commissioned for the Redaction Project, a series of prints created by Dwayne in collaboration with the visual artist Titus Kaphar. Created by Forest Young and Jeremy Mickel, the Redaction font borrows from and transforms classic legal fonts into a statement about redaction and the role of the literal and figurative imagery of fonts to make meaning.

The new typeface shows how even typography can be a form that produces meaning. Betts complicates each “form” of the poetry collection, whether it be the typeface or the received forms, all in order to excavate the personal and societal erasure of the human being; people are buried by our carceral society.

Taken as a whole, Felon is a magnum opus of what it means to live in American society, a society that incarcerates black men by the millions, a society that leaves people incarcerated without trial because they cannot post outrageous cash bails. When statistics such as the fact that the United States has 5 percent of the world’s population but nearly 25 percent of its prisoners fail to shed light on this inhumane epidemic, books such as Felon persuade us to look at the psychic and emotional tolls prisons and jails take on actual human lives. This sort of collection enumerates the best that poetry can be: a tool, a song, a gesture towards empathy, an enactment of living a life that continues to baffle.