Say you’re at the ballet. When you look up and around the egg-shaped hollow of the theatre it feels like you’re standing in a giant jewelry box looking up at a shut lid. It’s dark, save the small auras of light that come from the torches and gas lamps that line the walkways and the edge of the stage. The ballet you’re attending is Giselle and the first act is meant to be lively and bright: a series of orderly dances featuring happy peasants and a grape harvest. This is why you’ve come to the theatre, you think—for its magic. You’ve heard that watching Giselle is like entering a dream, particularly in the second act, when the lamps glow against a dozen women wearing muslin skirts so fine that it makes them into wisps, spirits haunting the stage.

But here in Act I, Giselle seems to be going mad. She has discovered that her lover, Albrecht, is betrothed to another woman and the emotional injury is quick and punishing. She dances unsteadily now, reenacting moments from their courtship for a moment, then falling into hysterics, her spindly fingers quivering. Again and again she staggers across the stage into her grandmother’s arms, then her lover’s, flinging her body from trap to trap until the pull of insanity grips her firmly. She tears her hair from its pinnings and collapses, dead, at the center of the floor. The theater grows quieter at the close of the first act. This is where the dream begins.

+

Giselle’s solos are a staple of a young girl’s ballet training—a preferred method for instructing students in Romantic Ballet choreography and technique. I learned and practiced them many times, beginning at age twelve, all of them beautiful and challenging. Still, it was her death scene that we’d beg to rehearse, scampering around our director, offering to stay longer if only she would play the music. We enjoyed it for its drama and novelty—the rare opportunity to not only let go of the delicate illusions of ballet, but come entirely unhinged. It was a rush to think that we could capture an audience with our imitation of decline onstage.

Still, there was some slim reality in it. I had blisters during those practices, and often in class our hair escaped from its tight coils, sprung free by the torque of pirouettes. I especially remember a suspended turn called a renversé which emphasized, not a pain yet, but a growing heaviness in my left hip.

+

But then, nightmares are the core of every ballet story. I trained in a studio filled with the legends of old Russian ballet teachers who carried lit cigarettes or sticks to dole quick punishments for failure or collapse. There were gruesome stories of tendons snapping and limbs suddenly awry, and always tales of those four-hour rehearsals going double their length because a director was unsatisfied. Our horror was delighted. We ingested this lore and made some of our own. We were sometimes forbidden water and the removal of our pointe shoes, no matter how raw the flesh was inside. We had a guest instructor who wouldn’t stop the music until we jumped higher. We compared wounds often. I broke a toe on stage as the Summer Fairy in Cinderella and finished Act III with a vice grip smile. Lily Krauss performed in The Snow Queen with a 103-degree fever. Melanie O’Keefe uncorked a kneecap more than once. Then there was the parade of spinal stress fractures. At one point, three of my fourteen-year-old friends wore orthopedic back braces with samurai pride, while my director, alarmed, required the rest of us to take Pilates. I was fortunate, I thought. I was strong to train so hard and remain relatively unharmed. And I knew what to do with strength.

+

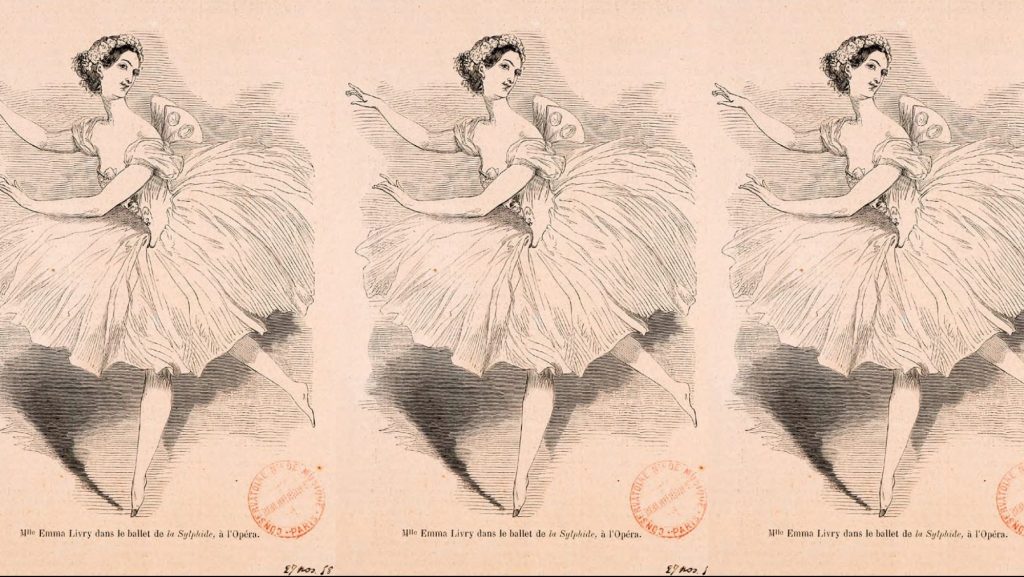

On a November afternoon in 1862, a 21-year-old French ballerina named Emma Livry prepares for a dress rehearsal of an opera in another jewelry box theatre. The opera is called La Muette de Portici, which portrays an uprising against Spanish rule in 17th Century Naples. She has dark hair and a simple visage, but the quality of her movements is unlike that of any other dancer the European stage has seen. She is incomprehensibly light, in defiance of the flat hard matter of the floor and the weight of her frame. In fact, Marie Taglioni, the reigning Italian ballerina of the era, has taken her under her wing, even choreographing her a solo called Le Papillon to celebrate her quality. Backstage, she readies her muscles, pins back her hair, and steps into her airy muslin tutu, leaving the yellowish and stiff version of the same skirt hanging in her dressing room, as usual. Perhaps her director pesters her to wear the fireproofed skirt, or not tonight. She takes her place in the wings in the heat of the nearest torch, gazing coolly into the flickering expanse of the stage which is outlined in more torches at eye level and gas lamps at her feet. Rehearsal begins.

With a brush of her skirt, a curious flame reaches out and discovers a taste for delicacy. Livry makes a flighty perch on the tip of her slipper and is ablaze, illuminated in the act of flying or falling before tumbling into shrieks of panic. It takes only a moment for a colleague and a fireman from backstage to douse her with soaking blankets and pluck smoldering tulle from her wounds. But her corset has been melted to her ribs. Nothing can be done but summon a doctor, who cocoons her in the dressing room with gauze. For 36 hours, everyone waits. By the time she’s removed from the theater to recover, the papers have named her the burned butterfly. For eight months, she lays still so as not to crack her scalded skin, accepts trickles of water into her mouth, until she dies. In that time, she may have pondered the acrid, sticky yellow tulle that would have hampered her art, but may have also kept the artist alive. One would expect her to regret her sacrifice, but I’d understand if she was proud.

Livry wasn’t the only ballerina who burned—there were many others before and after her who remain uncounted. But she was the only ballerina to make it an issue of authority and craft. No one could move as wistfully as Livry, and however much the Romantic tutu gave her the power of illusion, the chemical treatment took it away. In 1859, when the French government decreed that every object in theatres be flame-proofed, she wrote to the director of the Paris Opera: “I insist, sir, on dancing at all first performances of the ballet in my ordinary ballet skirt.” What could they do? She was the best the European stage had seen. They asked her to sign a waiver and she was permitted to wear her ordinary skirt for rehearsals as well. When she received the burns that ended her life, no one was in the audience watching.

+

For the Christmas of 2011, I received an Alonzo King Lines Ballet calendar from my mother. The photographs were shadowy and dramatic, the dancers posed in a black void, almost naked, donned in feathers, or whipping silk. The men leapt powerfully, but always precarious mid-air, arms and ribs splayed, head back, legs anywhere but underneath them. Their bodies arced like water flung. The women fell from risky postures en pointe or contorted in limby nests which seemed impossible to escape. All of them appeared to be composed of sharp angles between muscle and bone, stretched taught and teasing the notion that a body can rip—that theirs hadn’t yet.

The gift was meant to be inspiring—an acknowledgement of the boundary-pushing aspects of my craft, but its effect was somewhat different. By then I was sixteen and had just been accepted to the American Repertory Ballet’s summer intensive program, which seemed like my next frontier. But I also felt in danger of tearing at the seams. The muscles that cradled my left hip were protesting loudly now, and since I practiced and rehearsed six days a week, the pain I felt soon migrated from my body to my mind. I found myself hurriedly evaluating every moment of choreography (whether intended for me or not) for the challenge it would present to my heavy, electric, straining limb. Teachers prodded me, lifted my leg from its lowering angle, questioned my technique and strength. Heat built in my musculature, in my throat, and behind my eyes.

The angle at which my femur met my hip socket was the cause of the pain. This is what my surgeon told me after he operated when I was seventeen: that my bone structure would not allow my left leg to extend higher than ninety degrees, but I’d been telling my muscles to do it anyway. By the time I went to him, my hip flexor had torn my soft tissues apart. The iliac crest of the socket of my hip had crushed my cartilage until it was frayed and detached. After the surgery, the debris was gone, but the structure of my hip remained the same. To prevent further damage, he sliced my flexor to limit its strength and sewed together my rotator muscles to keep them from opening too wide. He prescribed a careful angle—just 45 degrees—that I would be forbidden to pass in my rotation. The examination room receded until I felt like I was sitting in a void. These were human limitations for human health: devastating to a dancer.

But I’d had some psychological sense of this outcome long before the surgery. When I flipped through that calendar on Christmas of 2011, I already sensed that I was nearing a threshold that marked the utmost limits of my body. And though I knew that reaching this threshold wouldn’t require that I end my career, I dreaded its demands for prudence and self-preservation, its crowded stage and sparse audience.

+

Last week, I traveled to Richmond to see my friend Elaine perform at the Grace Street Theatre. It’s unceremoniously bright in there—the seats beige and simple, the trim cream and blue—and the audience was thin, the heavy house lighting spilling like dishwater between small clusters of family and friends. But when Elaine stepped onto the stage, bare and deep dark, I fell in with her completely, my consciousness folding in and around her exquisite form draped in peach. Elaine has the most singular way of articulating her body, as if she can call upon every nerve and every cell to communicate the feeling she holds within—something intensely human, yet from another world.

It had been a year since I left the company. After nearly seven years of post-surgery performance, my hip had transferred its limitations to my spine, twisting my lower back into rotational scoliosis. This new development left me, for the first time, rather afraid. Jolts of pain and electric numbness struck unpredictably: at work, in rehearsal, in the car. I found myself willing to compromise, determined to find the place where perseverance and preservation intersect, but in professional dance there was no such place. To save my instrument, I discontinued its use. I finished the season and left the company.

But there in the dingy houselights of intermission, I wanted back in. I considered the knot of feeling that existed in my friend’s core, which transformed experience to dance and back again. It haloed her face, emotive and earnest, and lent true panic to moments of staccato. It hardened the shadows across her arms and abdominals made meaning from the nausea that’s been excavating her quadriceps and calves. It called out the spots on her hands and feet, all signs of her HIV. I considered my experience in the audience, my sense of drama and doom, and easily interchanged Elaine and Giselle. Neither had time to negotiate their limitations, only the physicality of feeling, and I was there to witness their all-or-nothing choice of dance on stage.

+

Late July, just months earlier, I had learned Elaine was HIV positive. I’d arrived to see her new house, expecting a tour and updates on her wedding plans or new stories about her Maine Coon cat, but she’d given me a glass of water and settled me in for the news. Her body was withered beneath her t-shirt. She’d not been able to eat properly for weeks, she told me. She’d nearly passed out while teaching ballet class to the ten-year-olds and finally called in sick to rehearsal when she no longer felt it was safe to drive herself there. Her doctors told her to slow down. Yet, here she was, body and mind still wiry and determined, fresh, showered, and clean. Elaine’s blood had kept the secret of its virus for two years, its contraction truly a fluke. But it was being honest now. Her muscular form seemed ready, we agreed, to become a stage for her experience of this T-cell rebellion. Now more than ever, she told me, it was important for her to perform.

There are periods when she does well. A few cocktails of medications have dwindled her viral load to twelve or so before they climb again, as they did just before the performance I saw. “It’s all good,” she said at the bar afterward, bourbon in hand, squinting into a grin. “We’ve got time to figure it out.”

She does have time. Though it first felt lukewarm to me in its optimism, Elaine’s easy response rings dissonant and true. Time is a dancer’s mooring. It constrains the use of our only medium, our bodies supple and willing for maybe thirty years, not long. But in our anchor, we find abandon: a reckless will to devour each of the infinite possibilities that mathematically exist in a finite space. If your career must end within a third of your lifetime, what reason is there to hold back? I picture the wavering darkness of Emma Livry’s dressing room, letter and pen at hand, and wonder how much time she thought she had to perform, what crazed ambitions ran through her mind—what variables she used in her calculations.

+

When I was seventeen and my training studio finally decided to perform Giselle, I was cast as Myrtha, Queen of the Willis. My kingdom was the ethereal second act—the misty, shadowed underworld, home of maidens who die of broken hearts and a newly fallen Giselle. When Albrecht arrives in search of Giselle, sick with regret for what he’s done to her, Myrtha quickly condemns him: he must dance until he dies. Albrecht lurches into involuntary flight, his time in the air his only reprieve, his labor increasing every moment he spends on the floor of the stage. And Giselle, ever generous and in love, dances with him, using her body to cushion his so that he can make it until sunrise without falling, giving him a chance against Myrtha’s curse. The audience looks on and the spirits swirl around him like smoke or a sorrowful human hurricane, their skirts making ripples in the air and light as they waft past.

It was beautiful to watch, I thought, particularly from my place on stage, but it was equally haunting. Hidden beneath my icy rendering of Myrtha, my body was trembling from my own four-minute solo, the mental and physical stress of its difficulty having made me incapable of eating anything beforehand but a package of Mentos. My bodice was soaked. Sweat stung my eyes. The sweep of my magic asphodel sprig had not brought us all to this struggle of endurance, this sink-or-swim test of pain. It couldn’t have.

+

I’ve discovered, recently, that I like moving in the dark, so I close my eyes to make it complete. It’s like I’m swallowed by infinite space wherever I am, yet no space at all, each motion a small prayer that I won’t meet a boundary, and a promise, perhaps, that I will. My dance is slow and measured at first; I twist in ways my spine will allow. But in this darkness, I find a desire for more—yes, that familiar recklessness, that disregard for blisters and hair flung from its pins. I lurch from the ground, by blessing or curse, my muscles in protest against the confines of the floor. And when I descend, it’s like falling into mist. How far did I fly? How long will I fall? I have only a moment to explode into these depths with everything I am before an ankle or elbow must brace for the floor. Still, I don’t open my eyes. Maybe dancing seems truest to me now when no one—not even myself—is watching.