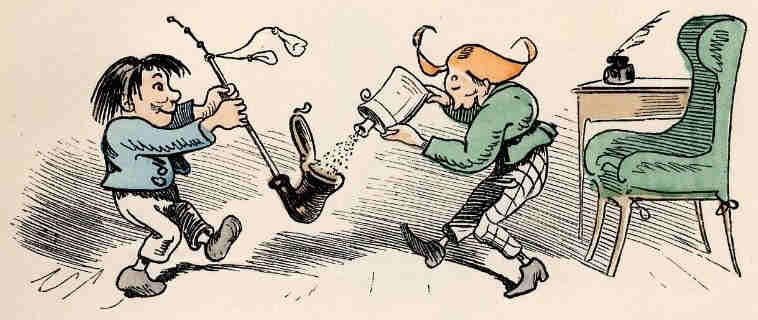

On a sunny afternoon in the spring of 1970, Herr Engler read aloud in German from a large, tattered book of cautionary tales about two mischief-makers named Max and Moritz, who tortured animals, stole things and played malicious pranks on their neighbors before being ground to bits in a mill and gobbled up by ducks. Engler stared intermittently through the open windows at the palm trees waving in a gentle breeze blowing over Monterey Bay , a breeze that did not quite clear the air of nicotine from the last class break. Using his fingers, Engler combed back a lock of wavy brown hair streaked with gray, which immediately fell again over his forehead.

As Engler read, his voice was childlike and his gestures impish. From time to time, he held up the book so we could see the cartoons, knowing we had trouble following rhymed German from one hundred years ago. Engler said that “German children find this entertaining,” and explained that The Adventures of Max und Moritz were popular in Germany when they first appeared in the 1860s, and remained so in the 1920s and early 1930s, when Engler was a boy. That was his point, I thought: if you really want to understand German, you must understand Germans, and if you really want to understand Germans, you must read what German parents read to their children.

Engler handed the worn book to Schimmel, who was seated on the nearest tablet-armchair and asked him to pass it around. Schimmel was thin with light hair, his nearly pencil-thin mustache and rimless spectacles. There were eight men in the class, each of us dressed in the uniform of the day: long-sleeve khaki shirts with thin black neckties, dark-green trousers held up by black web belts fastened with polished brass buckles, and shiny black shoes, except for the two green-berets who always wore their shiny black jump boots with the trousers bloused over the top.

As Schimmel passed the book to me, a piece of gray cardboard, folded in half to fit in a coat pocket, fell out, gliding onto the linoleum floor. Schimmel picked up the frayed document and handed it to me along with the book. The document stated in German that the bearer worked for the Russian military police. Inside was a cracked, black-and-white photo of a twenty-something Engler stamped in one corner with a red hammer and sickle and a date in 1945. I placed the book and Russian credentials on Engler’s desk without a word.

Engler stopped gazing at the palm trees, looked at all of us for some seconds and began to tell a story about how the Russian credentials had ended up in his copy of Max und Moritz, a story about how he came to be a lover of literature and language burdened by memories of war.

Engler spoke of studying law in the 1930s, which bored him, but discovered instead a taste for Russian and English. His facility with Russian took him to the Eastern Front as a general’s aide. He retreated from Russia in the general’s Mercedes-Benz, while others walked, long gray columns of staggering men and faltering packhorses, the corpses of men and horses frozen black in winter and thawed by the pale spring sun for the wolves to eat.

He spoke of singing “Oh! Susanna” to cheer up his general, and how the general transferred him to the Western Front, so that he might live with a little dignity in an American POW camp, rather than dying nameless in a Russian labor camp.

Facing American tanks near Frankfurt with several dozen poorly armed teenage boys and old men from nearby towns, he told them to go home and chose to do the same, though surrendering to the Americans was easier and safer.

He traded his pistol belt, binoculars, and map case for a slave-laborer’s stripped trousers, jacket, and round cap, and starting to walk, nearly invisible, toward Berlin, three hundred miles to the east, through a gray-brown mass of exhausted, hungry German soldiers and civilians shuffling west. He spoke only Russian to avoid the SS searching for German deserters and the Russians searching for German deserters.

Back home, the Russian military police hired him to interpret and gave him the credentials that now lay on his desk. Several months later, he fled in the night to the American Sector in Berlin when the Russians found out he had been a German officer.

I wondered what Max and Moritz had to do with Engler’s war story. Now I see what in his mind was an allegory about his generation of Germans, mischief makers, who tortured, stole things and played malicious pranks on their neighbors before being ground to bits and gobbled up. I wondered then, and I still wonder, if he truly forgot about placing the Russian police credentials in the children’s book for safekeeping or if he put them where we would find them, so he could tell his story. His sad brown eyes reminded me of my late father. I felt sorry for Engler–the first time I felt sorry for any German. Engler and Dad were both victims of a war they did not want.

Dad had said little about the war most of the time, but when he thought I was old enough, about eight, and the mood struck him, he would slump in his favorite overstuffed chair, crossing his legs on the ottoman, and try to tell me what it was like, drawing deep on a Chesterfield, blowing smoke from his mouth and nose, his wet brown eyes seeing things I could not see. I sat on the carpet, pressed my palms against my cheeks and was very still.

Dad remembered the Luftwaffe strafing field hospitals, using the red cross emblem on the tent top as a bull’s eye. My eyes widened as I imagined Dad scrambling from a hospital tent, carrying the wounded, as German bullets whined and dusted up straight rows in the ground, just like in war movies.

Dad spoke of U-boats torpedoing troop ships headed for the States, ships loaded with American wounded, and sometimes German POWs. “In the North Atlantic you froze in maybe ten minutes, if you didn’t burn or drown first,” he said in a flat voice, staring distantly. My mouth went dry as I imagined the exploding ships, the burning slicks, and the men in the freezing water, the strong taste of saltwater in their mouths, screaming for help that did not come in time.

Dad spoke of some American wounded – the badly burned, the multiple amputees, the emasculated – asking not to go home like that, and how he and the other medics played God, killing them with an overdose of morphine.

Dad hated the Germans and put his stories in my head so I would never forget what the Germans had done, especially to the Jews, and what he had done to stop them. But there was still room in my head for new German stories, my stories.

I enlisted in 1969 with a promise from the U.S. Army to attend the German course at the Defense Language Institute. Enlisting in the army was a peculiar thing for a middle-class American Jew to do in 1969, especially to train as a German interpreter, but I had to contend with the Vietnam War and the draft that was threatening to pull me into it as soon as I finished college. My dad wanted me to serve in the military. He felt it was important to show the rest of America that the Jews were as patriotic as anyone else and were willing to serve. It was one of the last things he said to me before he died from lung cancer in 1960, when he was forty-two and I was twelve.

When Dad entered the army seven months before Pearl Harbor, he believed World War II was a crusade for freedom. When I entered the army eighteen months after the Tet Offensive and Lyndon Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election, I believed America had stumbled into a civil war in Vietnam that American leaders did not understand. Out of respect for my father’s last wishes, I could not bring myself to dodge the draft, but I also did not want to fight in a pointless war that was already lost; that was my dilemma, and Dad was not there to talk about it.

I knew the American army was in West Germany to keep the Russians out, but it was also there “to keep the Germans down,” as NATO’s first secretary general explained it, to deter them from attacking their neighbors as Germany had done three times during the previous hundred years. Dad would have liked that idea, I thought, but was I just rationalizing?

A few months after completing language training, in the fall of 1970, I was stationed in Mannheim with the American Military Police. A German policeman named Schmidt showed me a cracked black-and-white photo of himself as a Luftwaffe pilot taken during the war – jaw jutted, cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, wearing a flyer’s fleece-lined boots and a cap tilted jauntily to one side. His gray hair still had streaks of blond in it, but his skin was wrinkled and had begun to sink into his cheeks, tightening over his aquiline nose and cleft chin. He reeked of tobacco, and the thumb and first two fingers of his right hand were yellow with nicotine, and his teeth too. He coughed frequently from deep inside, the way Dad did toward the end of his life.

My days working as an American MP with Schmidt and his team of West German customs police were mostly the same: an estranged spouse or lover or a vindictive neighbor would call the German authorities or the American Military Police to report someone in possession of black-market American cigarettes or liquor, and we would go after them. Some days I felt like Eliot Ness in Chicago; other days I felt like Andy Griffith in Mayberry.

Schmidt and his team had worked with plainclothes, German-speaking American military policemen before, but I was the first Jewish one, which made them cautious. Before long, I found myself thinking and dreaming in German, and I wondered what Dad would have thought of that.

One day, on our way to search an apartment, we heard a news story on the car radio about how the West German government accommodated the recently legalized Communist Party. Scherdel, a seasoned West German customs cop, was riding shotgun that day, while Schmidt and I rode in the back seat. Scherdel was a conservative Catholic from Bavaria, a former combat diver in Hitler’s navy, an early type of SEAL. As he listened to the radio story, Scherdel said trance-like to the dashboard, “What we need is a little Hitler.” In the rear-view mirror I could see our driver wince.

Schmidt turned to me, tilted his head, and raised his eyebrows into an apologetic face. I felt Schmidt was trying to be my buddy. As for Scherdel, he was an unreconstructed Nazi, a product of the Third Reich in which he grew up. There were millions of middle-aged and older Germans like him. A questionnaire broadly administered by the occupation authorities after World War II showed that between a quarter and a third of the adult German population had been members of the Nazi Party or party-related organizations. Like the American occupation authorities, who turned West Germany into a Cold War ally, I stopped looking for former Nazis and Nazi sympathizers because they could be anywhere.

In the 1970s and 1980s, years after my military service, my wife Fran and I hosted more than a dozen German graduate students at our home. Some arrived speaking English fluently, and some needed a few weeks to get comfortable with it, but all of them wanted to define their relationships with Fran and me and everyone else they met during their stay in America in English, to be bilingual, to seem almost American. This was in sharp contrast to the older Germans with whom I had worked in the army, most of whom spoke little to no English. Our guest students learned proper English in school, but it was from American Armed Forces Network radio, which broadcast American popular music, that they picked up the colloquial English of their generation. They had absorbed other American influences as well, and arrived wearing American-style clothes, eating American-style food, and watching American-style TV: jeans and T-shirts, pizza, and Kojak. Some were critical of America, but the majority took a different attitude. Who were they, as Germans, as citizens of a nation that started World War II, to judge America?

Critics and admirers of America alike agreed that only the United States and the Soviet Union mattered in the world of power, and they would not cast their lot with the Russians. To speak American English fluently, to study in America, and to be able to present themselves back home as Europeans who knew America– these were the things that mattered to the German-speaking students Fran and I came to know. That was the cornerstone of our personal relationship with them, and it was at the core of America’s special relationship with West Germany. After the TV series Holocaust aired in 1979, attracting the largest TV audience in the short history of West Germany, we talked about it with our visitors. One of them said, “We watched Holocaust to find out what really happened to the Jews during the Third Reich, the things they did not teach in school, the things our parents never talked about.”

“And what did you say to your parents?”

“We didn’t know what to say.”

Some of our older Jewish relatives and friends found our hospitality to German students incomprehensible. They asked, “How can you be nice to them after what they did to us?”

It was a fair and troubling question, but I had the sense from the younger Germans I knew in the 1970s and 1980s that they were confronting Germany’s Nazi legacy and rejecting it. Whereas older Germans remained nostalgic about that brief time when they were young and Germany stood on top of the world, younger Germans were not only willing to accept those truths but to assume responsibility for them. Our hospitality was not forgiveness, but rather a readiness to react encouragingly to gestures of friendship, acts of individual reconciliation from German members of our generation.

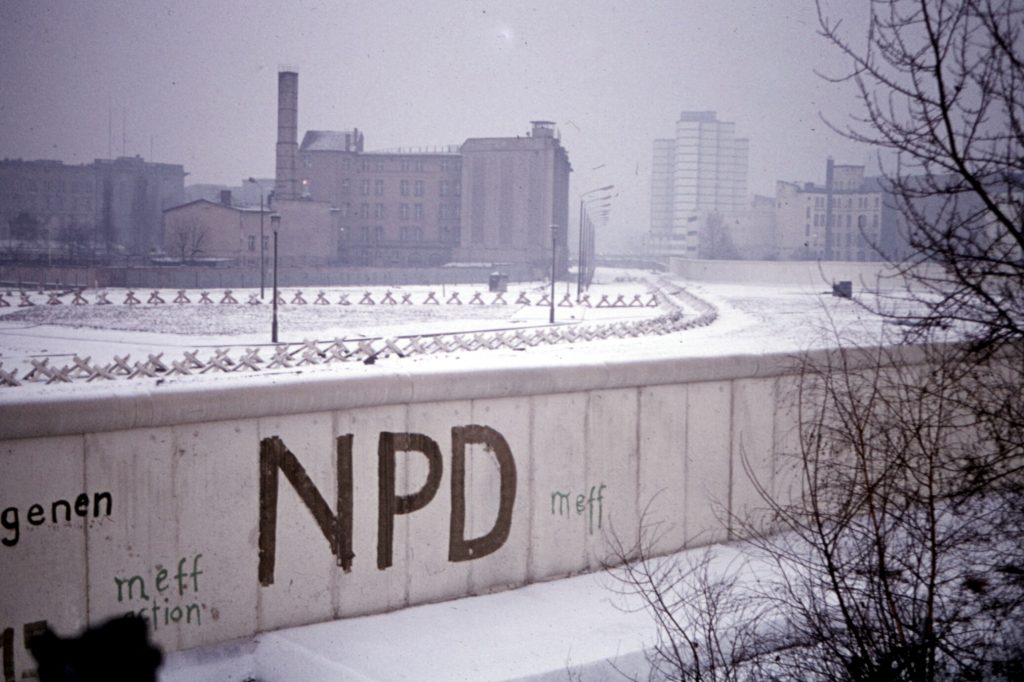

By the summer of 1991, when Fran and I returned to Germany for one of our frequent visits, all that marked the former border between East and West Germany near Rasdorf was an abandoned concrete guard tower about thirty feet high, still flying a tattered East German flag. It was easy to recall the barriers, the mines, the border guards, and their dogs, the way it was less than two years earlier, and the way it had been for forty years before. Like the rest of my generation, I had grown up accepting as normal a divided Germany in the middle of a divided Europe in the middle of a world divided between two superpowers. Now, the Cold War was over, and we had won, though I was not sure what that victory meant.

Fran and I were guests of our West German friends Michael and Karin, both our age, who wanted to show us a little bit of East Germany before it came to look like West Germany. The Russian Army was still there but going home. As Michael drove us around Brandenburg, the area surrounding Berlin, he told us about his grandfather, who was a prominent lawyer. Michael’s grandfather lived among the elite in the village of Bad Saarow, a spa southeast of Berlin. In Bad Saarow all that remained of the grandfather’s house was a foundation and a set of stone steps leading down to a lake. The rest of the place was destroyed by Russian artillery fire in 1945.

The Russians spared most of Bad Saarow and turned the town into a housing area and resort for high-ranking Russian officials. Michael drove slowly by several more properties that had once belonged to his grandfather. Michael’s family had hired a Berlin attorney to help them recover their property confiscated by the Russians. Michael stopped by the village hall to check on the status of the claim, expecting to hear more excuses from the East German bureaucrats. A few minutes later, Michael returned to the car and announced with some disbelief that his family’s property claims were all approved.

For Michael and his family, the Cold War and the Second World War were finally ending. And so, I sensed, was the special relationship between America and Germany, not just the mutual security interest that was disintegrating with the crumbling of the Soviet Union, but the largely unquestioned West German embrace of the American way of life. They would no longer need us to survive, so they would no longer need to flatter us by imitation. Starting the car, Michael asked me for the time.

“Time to go,” I said.