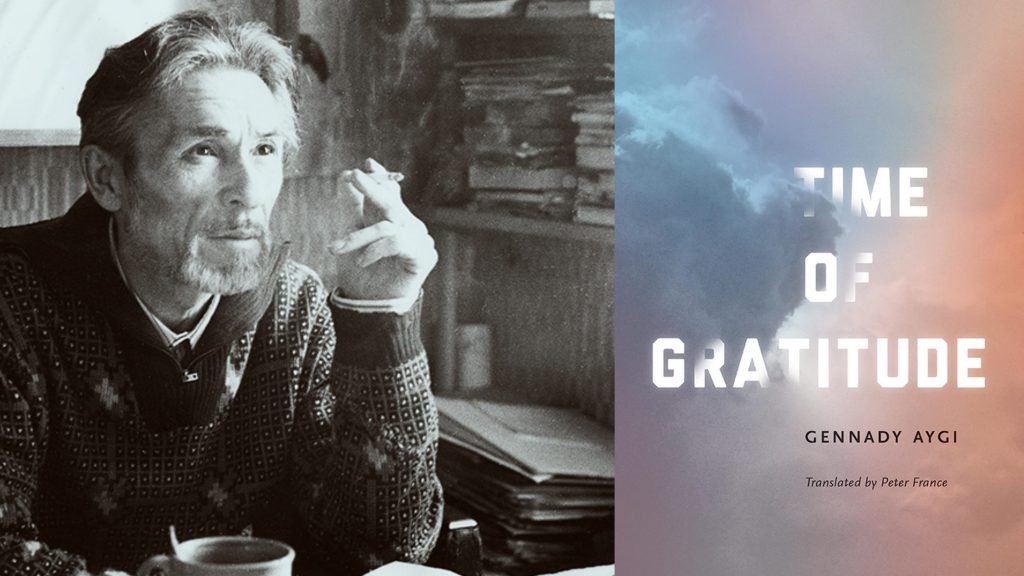

“The Word,” according to celebrated poet Gennady Aygi, “has begun to degenerate and has lost its significance as the preeminent creative force.” Born in 1934 in the Chuvash Autonomous Region of the USSR, Aygi remains one of the most significant writers of the so-called Moscow underground— a group of post-WWII authors and artists who came of age in the post-Stalin “Thaw” and yet found themselves unable, due to continued censorship, to publish or make a living through their work. Like his fellow experimental writers, Aygi found sustenance and provocation in the work of earlier Russian avant-gardists. His recent collection of essays, Time of Gratitude (New Directions, 2019), is his tribute to the legacy of such innovators as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Kazimir Malevich; Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchonykh; and his mentor, Boris Pasternak. Writing at a time when “poetry has . . . been transformed into sheer rhetoric,” “a self-contained game” whose “pseudo-despair” has “served as the basis for solid worldly careers,” Aygi implores us to look back to the revolutionary years of the 1910s and 1920s, both to take stock of what we’ve lost and to ask how these writers might yet transform our perceptions and our poetics. We should do so, he suggests, not only to revive our flagging faith in the power of the word, but also to unearth strategies for making our own writing more attentive, adventurous, and alive.

The Russian avant-garde, a diverse cultural movement which involved experiments in multiple artistic domains—from poetry, painting, and architecture to graphic design, photography, and film—reached its apogee in the years around the October Revolution of 1917. This was a time of historic catastrophes (famine, oppression, civil war, world war) twinned with utopian hopes. Between about 1910 and 1930, the idealism of worldly and ambitious young artists hit up against the limits of both personal freedoms and basic necessities. Unlike most of their predecessors, these authors were not aristocrats. Many of them came from the provinces and borderlands of the republic, from Belarus or Astrakhan or Georgia, arriving, often young and penniless, in the big cities where European influences, modern technologies, and an immense population of workers collided. The result was a new vision of art—un-ironic but deeply self-aware—as a technology for revolutionizing not only social structures, but the very structures of language and thought.

The Russian Futurists in particular—including Khlebnikov, Kruchonykh, and Mayakovsky; painters like Larionov, Malevich, and Guro; and filmmakers like Vertov and Eisenstein—argued that a break with prior traditions was essential for the renewal of the arts. “Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity. . . . From the heights of skyscrapers we gaze at their insignificance!” the first Futurist manifesto proclaimed. They sought, in ways that were often anti-metaphysical, even anti-aesthetic, to produce a sense of what Viktor Shklovsky called “enstragement” [ostranenie]: that shock of language that disrupts our dull, automatic view of the world and renews our perceptions. For the Futurists, to make art was to engineer disruption, to disconcert and to illuminate. It was to return to the most basic elements: primary colors and simple shapes, folk art (sometimes called “primitive art”), and the letters of the alphabet (from which Khlebnikov sought to craft a “universally intelligible language” based on sound). These artists were cosmopolitan, looking to Western influences like Cubism, and the work of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, and even Walt Whitman, while also proudly claiming an “Asiatic” inheritance of Old Slavic folktales and Orthodox mysticism. They treated paintings and poems as recombination machines, whereby ancient and cutting-edge, Eastern and Western, highbrow and lowbrow influences could meld to show us reality—as fellow modernist Wallace Stevens put it—“more truly and more strange.”

Aygi, who worked for a decade organizing exhibits at the Mayakovsky Museum in Moscow, implores us, in Time of Gratitude, to grasp the seriousness behind the Futurists’ irreverent, often idealistic approach to art. He writes, “One should never confuse the eternal (real and active) ideals of humanity with utopia or utopianism,” since, in Mayakovsky’s work, “there [is] much that has already become an aesthetic reality for all time—in the changed consciousness of millions of people” [Aygi’s italics]. In other words, Futurists like Mayakovsky were never merely utopian or fanciful in their views. Instead, they believed in the power of art to revolutionize everyday life by transforming people’s perception of, and engagement with, the spaces and objects around them. Their world-making was playful, but it was far from just a game. For them, as Robert Frost wrote elsewhere, “the work [was] play for mortal stakes.”

This sense of art’s “mortal stakes” came, in part, from the intensity of the Futurists’ historical moment. The overthrow and murder of the last czar, the ascendancy of Lenin, the victory of the proletarian revolution, and the attempt to build an entirely new government all took place in the midst of famine and a civil war that stretched from Ukraine and the Caucasus to the Russian Far East. Amid the widespread privations and violence of the revolutionary era, description itself could seem like a gesture of resistance. Aygi suggests as much when he quotes the long-overlooked Chuvash modernist poet Mikhail Sespel, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 23:

‘I see them at the station, starving people with terrible emaciated faces, in rags, fugitives from the Volga,’ [Sespel] wrote in January 1922 . . .‘In the recent hard frosts they were dying in droves in one place or another, sick, freezing people; their bodies were loaded by the hundreds onto sledges and driven away, open to the elements. . . . In the market place . . . these fugitives from the Volga lie barefooted, covered in sores, and dressed in rags—they beg for bread without saying a word . . .’ [Sespel] knew he was doomed: ‘My body is disintegrating like a corpse, there’s no stopping it,’ he wrote in his diary as early as 1920.

As exemplified by this passage, much of Aygi’s book is devoted to the rediscovery of a literary genealogy that history has tended to erase, often through a combination of censorship and violence. Thankfully, there is no returning to the extreme duress that was, for the Futurists’ art, both blessing and obstacle. But Aygi’s work is still infused with the tragedies of the twentieth century, including (in the words of his translator, Peter France) “global war, genocide, and the anguished loss of old beliefs.” Aygi’s particular spiritual intensity grows out of his close connection to both his pastoral homeland and Russia’s traumatic history. It is also, like the Futurists’ works, a composite of multiple influences: Chuvash folk beliefs, the Russian Orthodox mysticism of pre-modernist thinkers like Nikolai Fyodorov, and the works of European writers like René Char and Franz Kafka. Such features led the Soviet Writers’ Union to censor him as a “cosmopolitan” from the 1960s all the way up to the end of the ’80s; in our time, they account for the strange, enduring attraction of his verse.

There is a singular voice in Aygi’s poems, but no defined speaker. Certain passages give the impression that a point of view has been dispersed across the immensity of a Russian steppe, almost as if the poem were the voice of the landscape, ecstatically seeing itself, as in “Field: Bridge: Grasses” (1975):

shudder

revelation

in field in solitude

(yes: again not many yes: outside the village)

— just a few grasses like heads-of-light

somewhere in the waking gleam of the lightly distanced

yet still in my heart appearing

light and wordless sons. . . —

The content or import of the poem’s “revelation” remains an open question, but the sense of the smallness of any one speaker, and of the vastness of his surroundings, is palpable. The feeling one gets from many of Aygi’s landscape-inspired verse recalls the final line of Mandelstam’s great 1917 poem, “Golden honey flowing . . .,” in which “Odysseus return[s], full of space and time.”

Throughout his oeuvre, Aygi’s Futurist-inspired experiments with typography and punctuation create a visual experience that embodies the open expanse of both the semantic field and the literal landscape. The rhythmical structure of the original Russian gets drawn into tension, again and again, with the typography’s pauses and gaps, so that we move haltingly through an untamed space, open to whatever revelations may arise. In Time of Gratitude, Aygi writes of Sespel, his 1920s predecessor, that the latter’s formal innovations “were never individualistic ‘escapades’—they weren’t caused by any destructive tendencies, but by [Sespel’s] deeply organic striving for the ideal, the urge to create new, ideally just relations between people” [Aygi’s italics]. One could say the same about Aygi’s own poems, although their focus tends to be ecological and spiritual rather than explicitly political. Their starkness, hermeticism, and strangeness are not mere affectations but efforts to enact (and invite) listening on the page. He approaches the vastness of Russia with what he calls a “post-ecological faith,” praising even the emptiness after catastrophe as if he can hear the wind of history moving through it:

praise to the colour white — god’s presence

in his refuge for doubts

praise to the poor city the bright and beggarly age

to snows — that cut — with essence of colourlesness

the face — of god

to the bright — angel — of fear

the colour — of face — of silver

(“Bird from Beyond the Seas,” 1962)

For this poet, the whiteness of the Russian winter does not bespeak absence, but a reduction to the single most significant essence: the light of divinity. Aygi’s poems often stage an encounter with apparent barrenness that brings the speaker face to face with “fear” or “doubts”—the better to make him imagine even this “bright and beggarly age” as a “refuge.”

In our own age of Mayakovskian self-promotion, when it can seem that every poet must shout their individuality “At the Top of [Their] Voice” in order to get noticed, Aygi’s ecstatic selflessness can come as a relief. His voracious attention to his surroundings does not preclude him from treating the poem as an intersubjective space—one that seeks to erode the boundaries between the poet and his public. Compared to the jaded and world-weary verse of many contemporary poets (in Russia and elsewhere), Aygi’s poems, with their simple language and elemental image-system, possess something of the “childlike aesthetic” that scholar Ainsley Morse has described in the works of the Russian avant-garde. The disarming earnestness of his work recalls Il’ia Kukulin’s claim that “The ‘childlike’ [in poetry] is a metaphor for the fact that the close and personal details of the world do convey an atmosphere of the ‘personal’ and at the same time the ‘unknown,’ the ‘unknowable,’ something that in principle cannot be conveyed in words.” Aygi’s sincerity is so pure as to seem almost naïve—but, at the heart of each of his poems, as in the serious games of his Futurist forebears, a silence remains that knows more than it can say.

Such silence is not, of course, one of the things we tend to think of as crossing the borders of nations, languages, or canons. These days, we are likelier to focus on the global flows of capital and commodities, data and carbon dioxide, tourists and refugees, than we are to consider how poems can speak across the bounds of place and time. Indeed, when current-day thinkers look back to the modernist period, their tendency has been to bemoan how the negative (Fascist, nationalist) elements of the 1920s and 1930s have infiltrated our public discourse. But there were other, more positive modernisms, as the Russian avant-garde reminds us—even if the ideologies undergirding their works sometimes proved incompatible, or downright hostile, to everyday life.

Numerous scholars of the avant-garde’s aftermath have traced how its idealism soured into nihilism, and how many of its most utopian aesthetic discoveries came to be co-opted, with apparent ease, by the totalitarian Soviet state. The world we live in now bears few obvious traces of the avant-garde legacy. And yet, Time of Gratitude asks, what would it mean to take the earnestness, energy, worldliness, nerve, ambition, and commitment of the Futurists seriously? For Aygi—and, he suggests, for us—the Futurist legacy lives on as an invitation: to experiment boldly, to engage widely, and to trust in aesthetics as an engine for socio-political change.

Author’s note: I owe a debt of gratitude to Ainsley Morse, whose scholarship and conversation about the Russian avant-garde have enriched my thinking on the topic immeasurably.