Either the Perfect, or Absolutely Very Worst Ever, Book for Cat Lovers

1.

There’s much to love about Christopher Smart’s Jubilate Agno, but its most famous section is that about his cat, Jeoffrey. Smart calls him “a mixture of gravity and waggery,” which may be the most apt description of cats ever written.

But that’s hardly all Smart has to say about Jeoffrey: Jubilate Agno’s Jeoffrey section goes on for a total of 77 lines, some quite long (e.g., “For he will not do destruction, if he is well-fed, neither will he spit without provocation.”) and each beginning with “For…” Written between 1759 and 1763 when Smart was quarantined in London’s St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, Jubilate Agno—Latin for “rejoice in the lamb”—is marked by religious fervor, often-bewildering word emphasis, and frequent changes in direction. There’s a touch of madness to the overall poem, and Smart’s praise for his cat is no exception. Here are its last few lines:

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, tho he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face the earth are more than any other quadruped.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the music.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

I suspect the reason Jubilate Agno’s Jeoffrey section is the poem’s most famous isn’t simply because it’s about a cat and is funny. These lines accurately capture the peculiar mixture of lunacy and calm (ahem, “gravity and waggery”) inherent to cats and to owning cats. There’s a good reason the phrase is crazy cat person and not crazy dog person, as I, a long-suffering, deeply devoted cat owner, can attest.

Bohumil Hrabal’s All My Cats very much exists in the same “cats are wonderful, cats are evil lunatics, I am a lunatic for loving cats” space as Smart’s lines about Jeoffrey. Available November 26th, 2019 from New Directions, All My Cats is a memoir about just that: in the ‘70s, Hrabal bought a country house outside of Prague where for years he tended to a clowder of quasi-feral cats. But the book is so much more than Hrabal’s account of his cat stewardship. Really, what All My Cats is a stunningly revealing, occasionally deranged exploration of self, with cat ownership the frame through which that exploration is presented, by one of postwar Europe’s greatest writers.

Though his work is well-regarded by a small-but-vocal group of literary readers (e..g, the Wall Street Journal’s books editor once published a review of Hrabal’s Too Loud a Solitude), outside of Europe, or even the Czech Republic, Hrabal does not enjoy the level of name recognition and fame that he should. Folks, I—alongside All My Cats, the most unhinged cat-focused memoir I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading—am here to change that.

2.

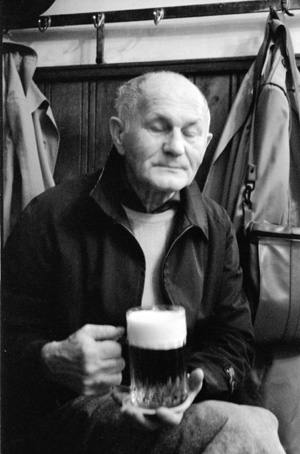

Hrabal, who was born in 1914 and died in 1997, supposedly after falling out of a window while “apparently trying to feed the pigeons,” was one of twentieth-century Europe’s greatest prose writers. His novels—including I Served the King of England (1971) and Too Loud a Solitude (1977/1980)—are clinics in how to write intimate character studies using exquisite prose. Hrabal’s attention to the line was poetic; in its attention to the details, his writing is akin to say, William Gaddis’s, albeit less apt to stumble over itself. Here’s an illustration of Hrabal at his best, from the opening of Too Loud a Solitude:

For thirty-five years now I’ve been in wastepaper, and it’s my love story. For thirty-five years I’ve been compacting wastepaper and books, smearing myself with letters until I’ve come to look like my encyclopedias—and a good three tons of them I’ve compacted over the years. I am a jug filled with water both magic and plain; I have only to lean over and a stream of beautiful thoughts flows out of me. My education has been so unwitting I can’t quite tell which of my thoughts come from me and which from my books, but that’s how I’ve stayed attuned to myself and the world around me for the past thirty-five years. Because when I read, I don’t really read; I pop a beautiful sentence into my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop, or I sip it like liquer until the thought dissolves in me like alcohol, infusing brain and heart and coursing on through the veins to the root of each blood vessel.

And now, for comparison, here’s a passage from All My Cats, also near its beginning:

I called the black one Blackie and the grey tabby Socks. Blackie was my favorite. I never tired of looking at her and she was so fond of me she’d practically swoon whenever I picked her up and held her to my forehead and whispered sweet words in her ear. Somehow I had reached an age when being in love with a beautiful woman was beyond my reach because I was now bald and my face was full of wrinkles, yet the cats loved me the way girls used to love me when I was young. I was everything to my cats, father and lover. But the cat with the white feet and the white bib, Blackie, loved me most of all. Whenever I’d look at her, she’d go all soft and I’d have to pick her up and for a moment I’d feel her go limp from the surge of feeling that flowed from me to her and back again, and I would groan with pleasure.

The opening scene of All My Cats is misdirecting, however, because the book changes significantly after its first few pages. After establishing the intense degree to which Hrabal loves his cats—do you, reader, “groan with pleasure” when you pet your pets?—the book quickly transforms into a recitation of woe, woe driven by Hrabal’s having so many cats. After all, the first line of the book is Hrabal’s wife asking “What are we going to do with all those cats?”, a question that quickly becomes a refrain and one Hrabal, who initially dismisses his wife’s worry, eventually, despairingly, asks as various cats are impregnated and litters of kittens begin to arrive. What are we going to do with all these cats?

3.

The answer, as we’re to learn, is cat euthanasia. Lots of violent cat euthanasia that leads to ever-increasing psychological distress for Hrabal. Over the course of All My Cats, Hrabal details his fondness for his cats, but how their numbers and the attendant chaos/filth, which cause his wife to “go about in a permanent state of seething reproach,” force him to cull the clowder, which leads to scenes like the following with his aforementioned beloved cat Blackie.

Prior to the scene in question, Hrabal had taken six unwanted “still-blind kittens,” placed them in an old mail bag, and “battered the contents of that mail bag against a tree, again and again and again.” His act—which he was forced to finish with an axe—leaves him feeling “crushed, suffocated by what I had felt compelled to do.” Then one day Blackie, the mother of the kittens Hrabal had murdered, came down with a fever, and began having convulsions.

And so I held her down, pinned her to the floor and called out to her and swore to her that I was right there with her, but she howled and spat and hissed at me as though she’d discovered it was me who’d killed her babies, that I was the guilty one, that my hands were steeped in blood and that the hands she had once loved now terrified her, and the realization of all that had driven her mad. The longer I held her down, the greater was my fear that, because she was so strong, if she slipped from my grasp she would fling herself at me, so I pushed down harder and harder. Suddenly, something snapped, and she went limp. I was still on top of her, and when I removed the blanket I saw that she was dead. One terrible eye was still open, staring at me, and in that horrifying eye I could see everything I loathed about myself.

Self-loathing and self-loathing’s dark cousin—suicidality—are frequent themes of All My Cats. Indeed, suicide recurs in Hrabal’s work: the protagonist of I Served the King of England attempts suicide during a moment of despair; the protagonist of Too Loud a Solitude commits a sort of suicide at the book’s end, encasing himself in paper and turning his compactor on; and Closely Observed Trains—made into the striking 1966 film Closely Watched Trains by Jiri Menzel—closes with a suicidally heroic act by that book/film’s protagonist. And whether Hrabal’s own death was an accident or not has been asked.

In the case of All My Cats, a chilling prediction from a fortune teller, who “predicted not only that I would become a writer, but that I would find myself in a situation that would drive me to hang myself on a willow tree beside a river,” haunts Hrabal, especially because there is a willow tree next to a brook near (or on) his property in Kersko, which he finds himself thinking of in the pits of his cat-related despair.

Though the book does not really come across as allegorical, the book’s recitation of cat-related woes (which Hrabal inflicts upon himself, by euthanizing his cats and being wracked with guilt thereafter) can be read as an analogue to Hrabal’s treatment by the state and of his own career. Following the Warsaw Pact, Hrabal’s work was banned, and a number of his books were published in samizdat. After several years he was once again allowed to publish “officially” after participating in what turned out to be a sham, pro-regime interview (in which Hrabal was an unwitting participant), a move that was seen by some as a betrayal.

There’s a late scene that comes close to addressing Hrabal’s issues with the state head on: he is called “to appear at the local National Committee office as witness” because his neighbor has been accused of “shooting and killing songbirds and squirrels through a closet window.” During the course of the hearing, the complainant grows heated, turns on Hrabal, and alleges that “those cats, [Hrabal’s] cats, caught and ate birds, especially when [Hrabal] wasn’t there, and if that kept on there wouldn’t be a single bird left in Kersko.”

In keeping with the askew tone of All My Cats, the accusation leads to a moment of catharsis for Hrabal:

When I heard that, it all started to make sense, and for the first time in a long time I had a wonderful feeling that in fact, by getting rid of my kittens and my cats, I had actually made it impossible for them, like Mrs. Soldatova’s rifles, to wipe out baby birds in their nests or in the trees, and I silently gave thanks that I’d been called as a witness to that hecatomb of songbirds, and that therefore my actions, my murders, meant something, because in fact I was helping to conserve the natural world.

Me? I think I’ll go pet my cat, even if the annoying weirdo refuses to sit on my lap, and even if he meows too often, and even if his litter box, which he barely uses correctly, is inherently disgusting. Maybe I’ll get a dog someday. Or a nice fish.

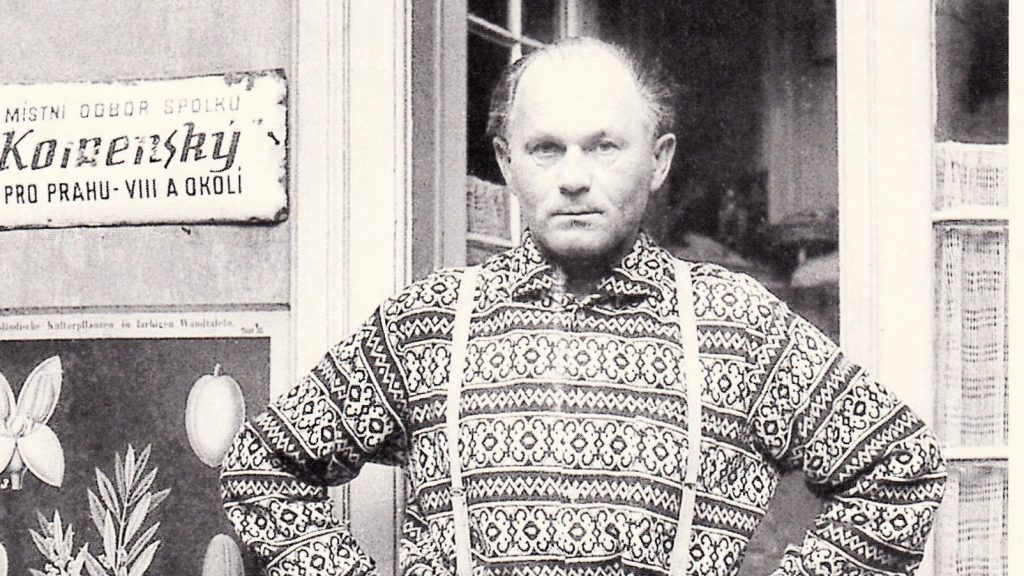

Header image via the David Short flickr photostream. Mural of Hrabal via Wikimedia Commons. Hrabal enjoying a beer also via Wikimedia Commons.