“The seasons and the years came and went. A Walloon autumn was followed by an unending white winter near Berdichev, spring in the Département Haute-Saône, summer on the coast of Dalmatia or in Romania, and always, as Paul wrote under this photograph, one was, as the crow flies, about 2,000 km away — but from where? –and day by day, hour by hour, with every beat of the pulse, one lost more and more of one’s qualities, became less comprehensible to oneself, increasingly abstract.”

“The Emigrants,” W.G. Sebald

Luang Prabang, Laos, December 2012: At some point in the middle of each night, somewhere, someone plays a gong. The metallic liquid sound ripples repeatedly inside my sleep. (It is urgent). And like a dream, it is closely familiar, as if it were coming from within my body, but impossible to decipher.

The meaning is urgent and has to be repeated, each night, as a ritual. It speaks directly to the sleeping body, it ricochets gently on skin, it penetrates my inner organs and my marrow softened and rendered porous by the night. It says: “It is the hour of the river: the river of sleep, the river of blood, the river of night and the two others we call Mekong and Nam Khan too. I beat now within you so you can remember to listen to your silence, remember that you are sleeping. And within your sleep there is only me that is a sound that is a silence that is a river.”

I do not know how to shed my childhood, this old snake’s skin. My childhood weighs on my bones and hinders all my movements.

A super 8 movie from 1976. I am two. Winter in the Dordogne. The skies and the river waters fuse together within one same mineral gray. I walk by the Dronne river, alone, a tall wooden stick in my hand that I pretend to use as a walking stick. I am wearing red woolen stockings, blue plastic boots, a marine blue corduroy skirt, a hand-knitted wooly pullover. My chestnut hair in my eyes, victims of an overgrown bowl haircut. I gather large, soft gray pebbles and I throw them in the waters, as far as I can. I love the sound it makes when it hits the surface. A dark green sound that speaks of the unseen that shapes and reshapes itself just below the surface, endlessly. I love to smell the river on my skin and my hair: it smells of mud and plants and stones and sun, sun in the river water even in the dead of winter. Throwing flat pebbles in rivers is what I love to do the most.

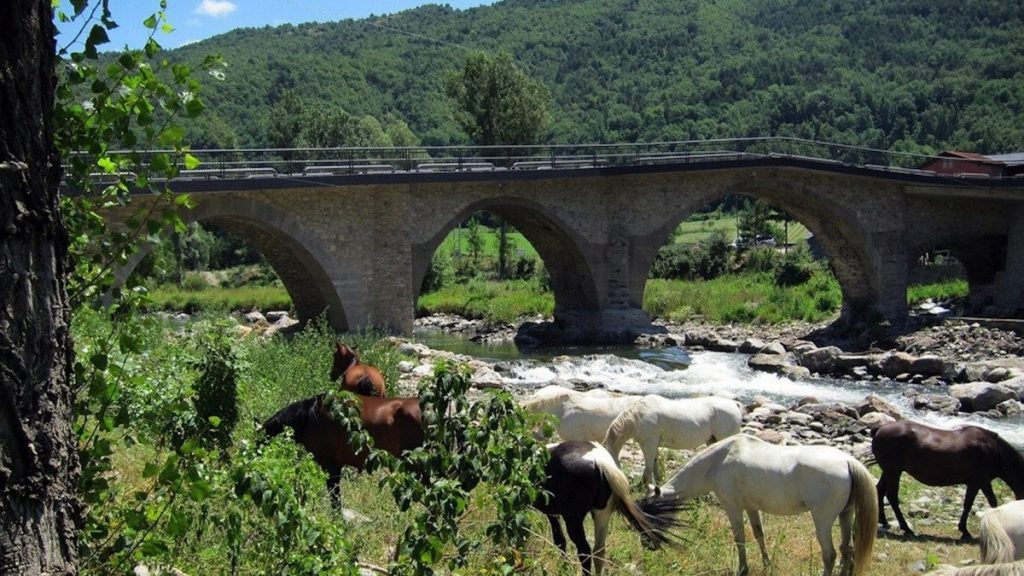

May 2004. The river is green and serpentine. Some parts are shallow and then there are holes. All of a sudden the water gets very deep. The water is cold. We are somewhere in the countryside, an hour or so north of Marseille. I never looked at a map to find out where exactly. The river is surrounded by trees. What type of trees? Oaks? Poplars? Willows? I wish I could name them. The trees, their foliage, color everything green: the river water, the sunlight, our skin, our hair. The rocks by the water are covered in moss. I choose the largest, most comfortable mossy rock in the green shade. I make a pillow with my sweater. I lay down, curled up on my side. I fall asleep instantly.

When I awake, Jérôme is here, with Patrick and Sandro. The three of them are standing in a circle a bit further away. At the center of their circle stands a camera on a tall tripod. They have placed it on top of the highest rock, roughly ten feet above water. They are whispering and their voices are partially covered by the lulling sound of the current. The current is strong, but not dangerous. Just below the rock where they placed the camera, there is a hole where the water gets very deep. Jérôme looks particularly tired. He wears a very old dusty blue cap with the visor on his neck. Tufts of yellow hair shoot out from the brim. He has dark hollows under his blue eyes and like all of us since we started shooting the movie he lives mostly on coffee, cigarettes and the pasta that Julie cooks for us around eleven at night when we are done for the day.

Jérôme admitted once to me that he envied my capacity to fall asleep literally anywhere. I could tell him that it’s mostly due to a severe iron-deficiency anemia (and not some bizarre and not very practical magical power) but I don’t. Whenever I fall asleep he starts whispering, then his whispering becomes contagious and everybody whispers on the set. When eventually they need me for a scene, he always wakes me up with the greatest gentleness, and guilt in his voice: “Sorry we need you again, but not for very long hopefully. Then you can go sleep in the car if you want. Patrick will give you the keys.”

Today, maybe for the first time since the beginning of the shooting, I am already awake when they need me. Nevertheless there is guilt in Jérôme’s voice when he finally turns away from his camera and addresses me:

“So I have an idea for this scene but before I tell you anything I just want you to know that you can say no. It’s totally ok. We can all rethink our plan if you say no.”

I already have a pretty clear idea of what he is going to ask me.

The summer of 1996: a small river whose name I never knew, near Epeluche in the Dordogne, its violet waters full of mud, stars and algae. The beach, nothing but mud, cratered by the hooves of a thousand thirsty cows. At night I float on my back, I listen to the singing of frogs and the rustling of leaves and the sleeping waters, dreaming, and I breath in the nocturnal exhalations of the wet bark of oaks and poplar. I remain equally porous to sky and water. I make a wish: a map that would also be a river, carved on the skin of my back.

“Come with me.” Even though we are both roughly thirty, Jérôme has a tendency to direct me as if I were a child. Maybe more accurately an extra-terrestrial child, with whom he would have a common language, but whose reactions are difficult to predict and whose answers are a bit cryptic. Like when I felt impelled to tell him that life was but an infectious state of matter (something I had just read in Thomas Mann’s “Magic Mountain” and wanted awkwardly to share). He did not comment, but asked me if he could record me saying that sentence only: La vie n’est qu’un état infectieux de la matière. And I thought that was his way of saying “I really cannot listen to you right now. But maybe later in life.”

I like being directed. Oriented. I like being asked to count my steps when I walk. I like not being required to speak (it is a silent movie). I like waiting. I love waiting for hours, literally, in between scenes, and falling in and out of sleep and observing people preparing a scene: delimiting a territory, calculating distances between faces and objects, artificially changing how shadows fall, experimenting, discussing. I understand how acting is disappearing, becoming no one. Just a projection. Just a shadow.

The summer of 1998: I cut my foot in the Dronne river on a sharp rock. A large cut underneath my right big toe. I sit on a mossy stone and watch the blood lost in clouds and volutes dissolve into green water. A moment of pure happiness. A cold summer day, no one by the river. On an impulse I had left my bike and entered the river without undressing. But now I cannot walk. I cannot bike. I remove my bra and let it dry on the handlebars. I smoke a cigarette and wait for my brother to come rescue me with our mother’s car.

I follow Jérôme towards the camera. Patrick looks mildly stressed. He looks at me the way a grandmother looks at a grandson who needs his tonsils removed but does not know it yet. Sandro looks happy and relaxed. Sandro always looks happy and relaxed. He communicates with us in Italian, English and some occasional broken French and reduces his conversations to the minimum. So I have this illusion, reinforced by his very clear blue eyes and his constant child-like smile, that Sandro is, in life, regardless of any external force, always happy and relaxed. Jérôme speaks again as if he is addressing the camera, not me, patting the camera gently and absentmindedly on the head:

“So we were thinking it would be a beautiful shot if after you get struck by lightning we would see you fall backwards in the river and then carried away, as if dead, by the current.

Yes.

Yes?

I agree. I think it’s a great idea.

So that’d mean we would want you in front of the camera, right here. And you should grasp the tripod for balance and place your heels as close to the cliff’s edge as possible. Sandro and Patrick will be on either side of you holding you too so that you don’t fall. That is, so that you don’t fall too soon.”

The memory of a snake once seen in the Vézère. I am eight. The river in the summer is golden brown and so shallow that it is impossible to swim. Instead you must pretend to be a lizard and crawl against current, knees bruised by sharp stones. The viper is also golden brown, the same color as rocks, the same color as the river, its slim body, endless, undulates against current by my side. The viper becomes viper, instead of just water and rocks, slowly. Terror and beauty fuse within the memory. Because the current is so strong and because the viper is between me and the river shore, we remain, the snake and I, frozen in time against current.

The scar. The scar is red and looks like a river.

The last day of the shooting of the movie. Noon. The large metallic carcasses of cars everywhere are too hot to lean on and offer no shade. The make-up artist, a chubby girl in her early twenties with short black and pink hair, is a specialist in gory make-up. We are all gathered to spend the entire day in this car cemetery to shoot the final scene.

I am to spend four hours sitting straddled on an old camping chair, my bare back against the unforgiving sun, while a scar is being drawn. I am dozing uncomfortably, my heavy head resting against my folded arms. I imagine that the tools the girl is using to paint my back ressemble the stylets of insects and their touch is cool and bizarrely soothing. I am nothing but frail translucent skin and ribs, ribs everywhere just under the skin. Ribs that form a wide cage protecting a hollow inside.

It is hard, even now that fourteen years have passed, to justify my enthusiasm and express my gratitude towards the person who asked me to gently fall backwards from a cliff into a river and then play dead. It was as if Jérôme had created a character that was the nocturnal part of me, the one who sleepwalks, who has lost her tongue, and desires forever to fall slowly backwards and then be dissolved.

The moment when I hold on to the tripod of the camera, my heels carefully placed on the edge of the cliff, is a moment of pure joy. A rare moment of feeling fully incarnated and present and being part rock, part sky, part river.

Patrick is on my left, Sandro on my right, Jérôme behind the camera in front of me. We are performing something that reminds me of a religious act, or a magic trick. Something is about to appear and disappear simultaneously. Something is about to take place, but not for real. Something, invoked by us, will manifest itself, be briefly captured in light, but will remain intangible.

Patrick is the only one who is genuinely worried, but I have not noticed. He is concerned by my enthusiasm for falling off cliffs in general. He is the only one whose intuition tells him that I like it too much. His hand on my shoulder has a very different feel than the hand of Sandro. The hand, unsure it will let go when it needs to, has a metallic quality on my shoulder. There is a short countdown. I let go. I feel all my muscles relax at once. The dark blue rain cape I wear spreads and flaps softly like dark wings. Everything softens and dissolves inside and outside simultaneously and when the water hits my back, I do not feel the cold. I do not feel. I close my eyes, I float, I let the current twist my spine, fill my ears, play with my hair, push me like a fallen dead leaf.

Often when I do recognize words in my native language, they are no longer automatically attached to a fixed meaning. Like the word rivière. I no longer hear it as river, but as a series of three imperative verbs:

–Ris! (Laugh!)

–Vis! (Live!)

-Erre! (Wander!)

I am in need of sunshine but I am not able to bear it for very long. I prefer dark places. I am always tired. I sleep on the movie set the way later in life I will witness Mexican dogs curled up near a big rock or against a tree or behind a car, sleeping.

I like to feel the hands of this unknown woman on my back, painting my scar. I imagine she is writing a long letter on the skin. Or perhaps just the same sentence over and over again obsessively, but sometimes she is changing the order of the words. Whether or not the letter is ultimately addressed to me is irrelevant. I am grateful something is being written.

A foudroyée, or ‘woman struck by lightning’ was my role. I never auditioned for the part, had never acted in a movie, would never act again and had never voiced any interest in the project. Here is what I roughly understood of the plot: a young man working night shifts in a grand dilapidated hotel, finds the fragment of a map. He leaves everything behind when he does and walks toward the river indicated on it. Meanwhile, elsewhere, I am caught up by a storm while hiking alone in the mountains and I get struck by lightning. I fall in a river unconscious and drift away. After that, I don’t think I knew then how it ended.

When the young protagonist follows his torn map to the riverside he discovers me there, sitting by the water with my backpack burned by the lightning still on my back. I do not speak and it is unclear if I can or if I have forgotten. I do not show much interest in his presence but I am attracted by the sunlight refracted on the golden buttons of his red velvet uniform. I want to bite into them, the way that two-year olds always want to swallow the sun. I decide to stay with him. Or more accurately I make no decision of any sort. I do not ask questions. I seem to act as if deprived of past and future.

The last scene takes place at the back of a tiny old Citroën van from the fifties (unexplicably full of glass vials that make beautiful crystalline sounds everytime there is a bump in the road). I am wrapped in a woolen blanket that scratches my bare skin. My character and my anemic self share an abnormal craving for sleep and my eyes keep rolling upwards in their sockets. The lulling of the glass vials soothe me. As the blanket slowly falls off my shoulder and my head rolls gently forward, a long deep scar appears where the lightning has struck. It runs through shoulder and ribs and backbone. The scar tissue, an intricate landscape – mountains, a river. A map.

The last image of the movie is a hand holding a torn map against my scarred back and a new image, a new path, part river part skin, taking shape.