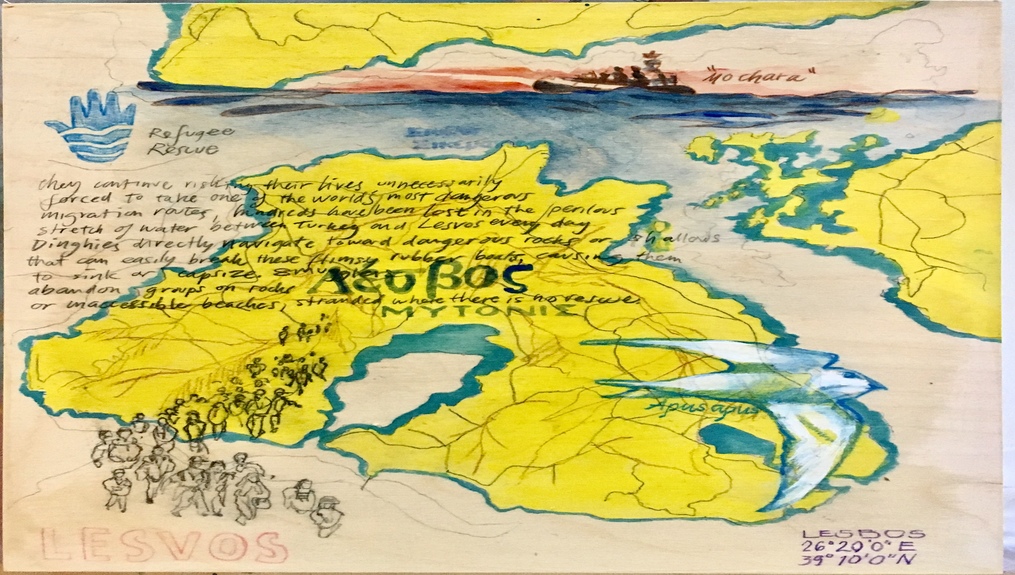

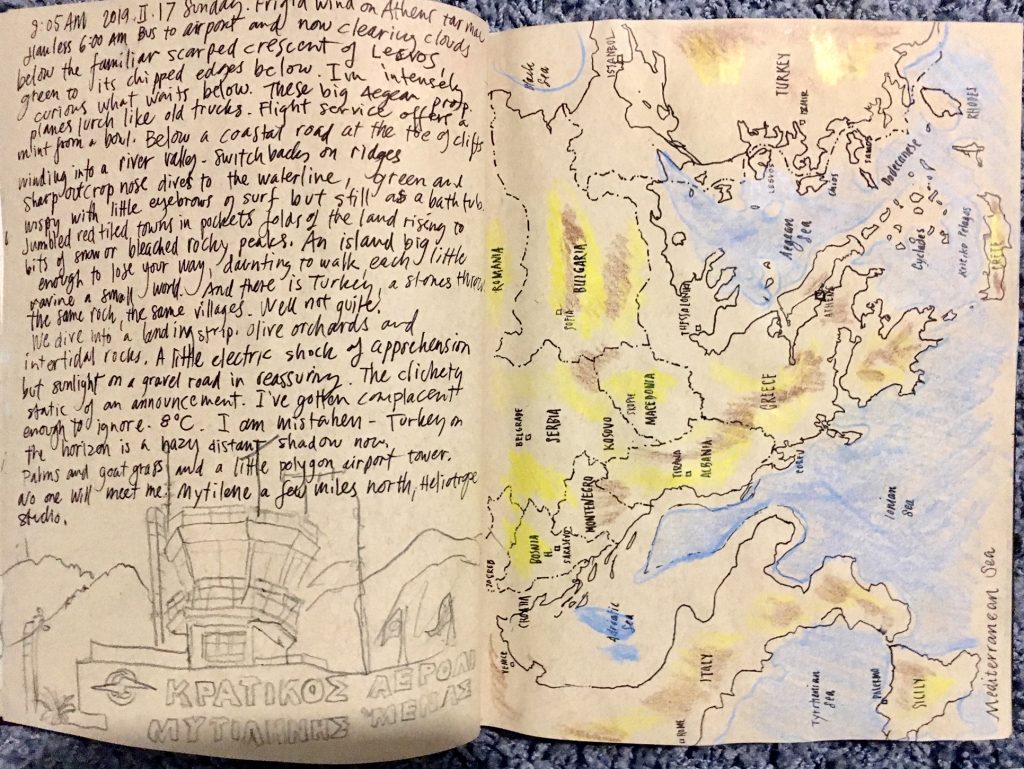

The following drawings and journal entries are excerpted from a personal diary kept by artist and cartographer Mark Adams, during his time working at One Happy Family, (OHF) a community center for people on the move, serving residents at Moria refugee camp, in Lesvos, Greece. (February, 2019)

Monday-Tuesday

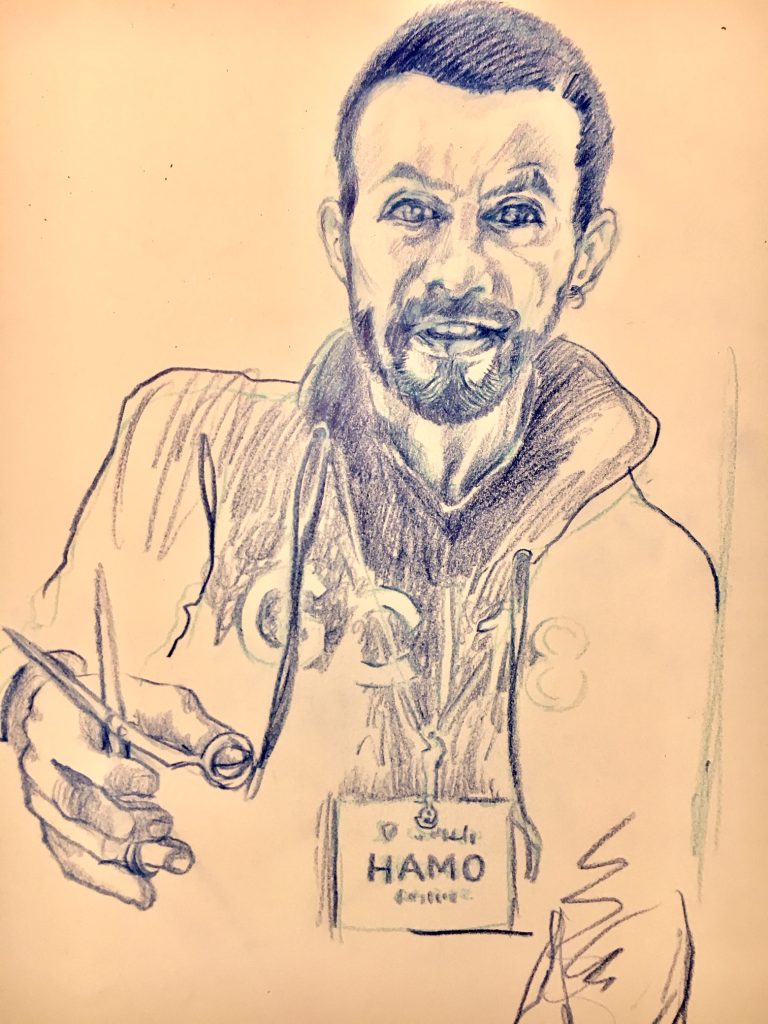

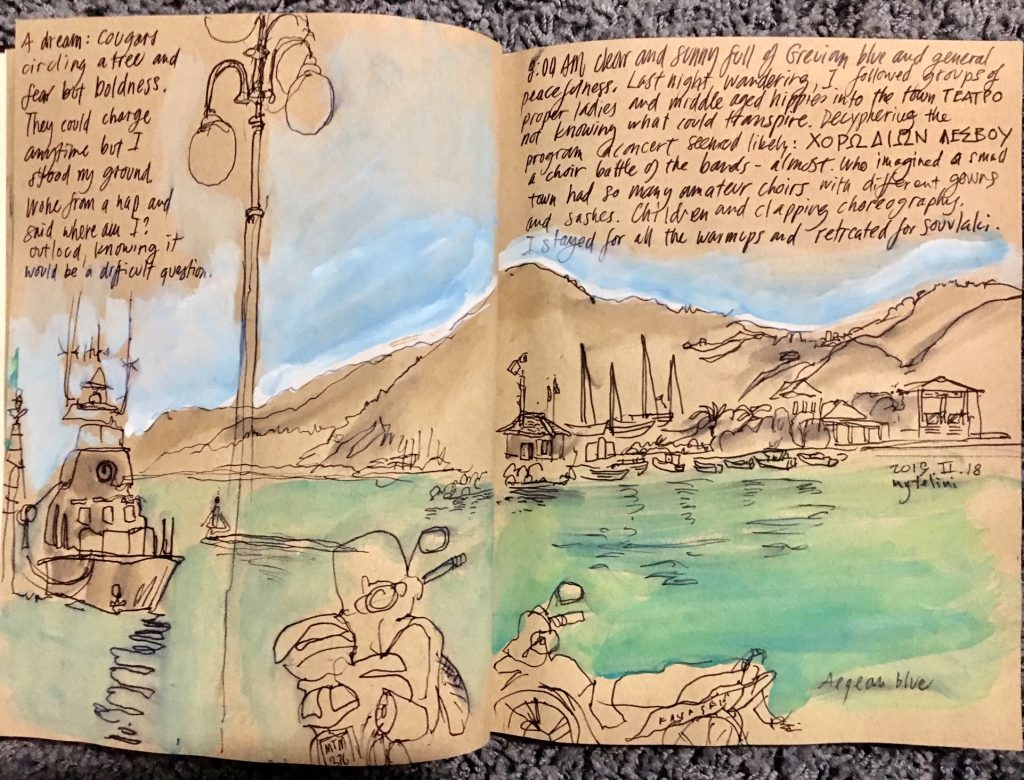

I am at the meeting point at the jetty by Mytilini Harbor just after 8 am. A lone slender bearded figure sits and smokes by the quai (he is H___ the barber, I learn later). Instead of approaching I retreat to dash off a sketch of the harbor mouth and a little coast guard tug against the rising terrain. Then the van pulls up and out of the corners of nowhere, 5 other volunteers converge, Germans and Swiss-Germans, a woman from France, the Israeli coordinator, all yet to be met. Ten minutes away and a crowd waits at the gates of OHF though they won’t be let in for more than an hour – they’ve all walked from Moria to spend the day here. I first saw OHF last spring, the pavilions, dusty soccer pitches and garden plots, overlooking the wide channel, 5 miles between the Turkish horizon and this Greek island. My first morning and there is not much acknowledgment from anyone – people come and go all the time. But the waiting refugees glance with sideways smiles, muffled by the strangeness of languages and foreignness, me and my pale straight hair and paler face.

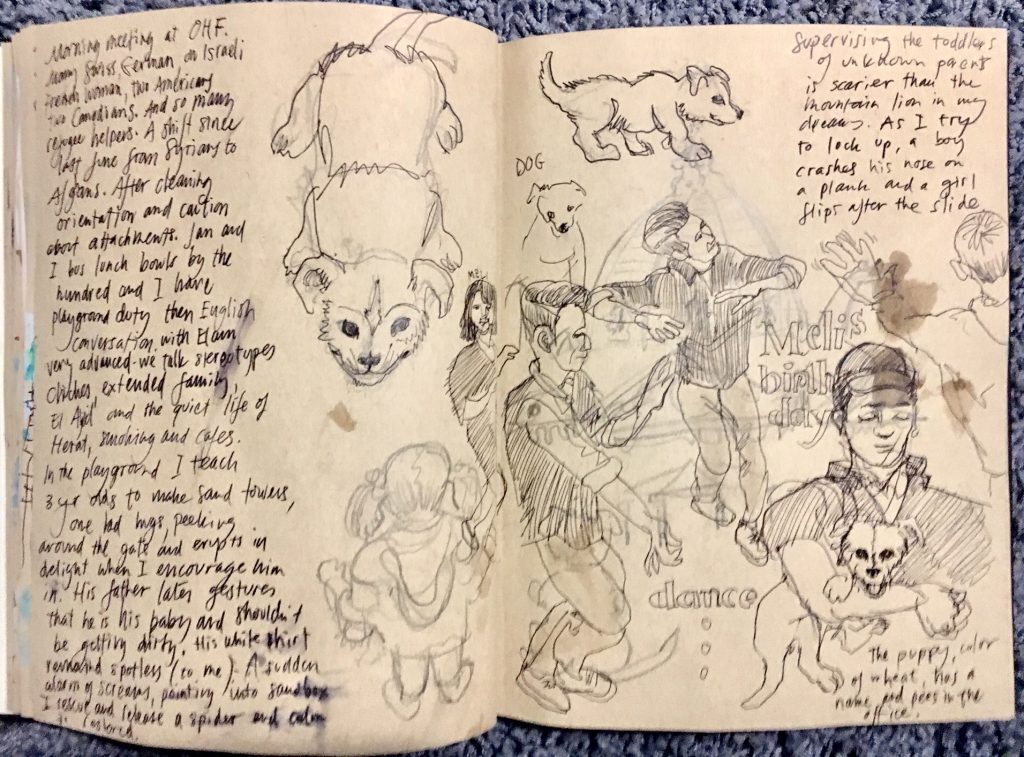

A boy leaps the fence and is inside then outside in a comic turn. Once inside there is a morning circle of volunteers and assignments, all still a mystery, and a nmemonic name game: Anka, Meli, Fabio, Luis, Jojanes, Akis, Chochin, Felix, Valentin, Bethany, Capuchine, John, Kristen, Jesse, Jan, and a larger group of long-term refugee helpers in yellow vests who do security and translate–their names are a different cultural slice: Mohammad, Ali, Ebrahim, Aziz, Hammad, Alem. Then we sweep with old brooms twisted from use, gray dust retreating to corners. There’s a perfect tiny sand-colored puppy running in wagging circles and several cats. Orientation for today’s new arrivals hits the notes of self-care and potential trauma, drachmas and etiquette, goals and personal missions. We are all rather young except me, but most have made migrant support into career paths. OHF now serves mostly Afghans — many of the Syrians have apparently moved on to Athens or Thessaloniki having gained asylum status. The flow has its mysteries, but the Afghans remain since they are not from a war zone and have no protective status with the EU.

The day revolves around the meal, bulgar and peas with tomatoes and garlic cooked in two giant caldrons on gas jets set in the floor, estimates at 800-1000 diners per day. I ferry the colored plastic bowls to a washing squad through a window in the cooking shed. Cheerfulness and order rule, a kind of shy politeness, dodging rocketing soccer and volleyballs wildly astray. The refugee security helpers keep the queues in order, separate the lines for women and children, not a trace of visible tension, aside from several well-known youngsters who keep queueing up for seconds and are scolded off.

I am assigned the playground to watch, a small sandy enclosure with rope netting, a slide and swinging bridge on a wooden adventure castle. I see no children and wonder if I need to round them up but as I unlock the gate a dozen appear in a few breaths, none can be much older than five. Most of the parents sit with their backs to the fence, barely nodding at me. My role is unclear. I don’t think I should play with them but several need a demo of the sand bucket / castle molding process and they shudder with delight when I un-mold some cylinders. They want me to do it for them but finally get their mimicry down and are non-stop, looking for me to shine my delight back at their success. One lad in a buttoned white shirt hugs the gate in shy defeat no matter how many times I gesture him in — until finally he plunges. This victory is snatched away as his father arrives, “MY baby,” he thumps his chest and mimes dusting the dirt off his trousers, before he disappears again. The damage is done I suppose, I’ve ruined his boy. The father doesn’t reappear even as I am rushed to lock up and the white shirted lad is the last holdout. Then a final chase scene, a game of tag, through wooden tunnels ends in a loud crack as a different toddler goes down and does not rise. the terror of playground monitoring is complete. He’s perhaps broken his nose — his mother is steady but not freaking out. Someone will round off that two-by-four later. The paradox of the journey, the miles at sea in leaky rafts, the rough camping along the way — what can be the harm of a playground? Or I imagine the reverse, “I didn’t bring you this far to kill yourself on a slide!”

Either way, washing dishes will be a relief.

And it is, but side by side with the cook from Zimbabwe, her story naturally comes out as each bowl is passed through the suds. She tells of another conflict that follows a pattern: the military who supported Mugabe also have his successor in their pocket. Authoritarian greed squeezes the people and makes living impossible. Even as Zimbabwe has become primarily an urban country, living below the radar of politics in the countryside is rarely possible. F___ has left her three children behind to escape in whatever hope of bringing them to a better life. I’m not about to probe and we talk around about: catering large dinners for the rich, the cooking skills from her mother and grandmother that feed a throng when it’s called for, the skills, she says, of knowing you can do something that seems as impossible as feeding a multitude. I’m not sure what I may ask and try to open my entire face into listening.

Through the office window we dispense soccer balls and decks of cards though quickly I see that these are shabby and used and often leaky or incomplete. One Jenga set is in constant demand. I also enroll them in Farsi-English or Greek classes. All the classes are mainly full and there’s a two week wait. One African wants French but we have no instructor. My basic French is not handy enough to convince him that there is no choice but to wait until March. We handle their identity cards and file them for the balls and games checked out. I’m intimidated by these precious documents, vital for their EU stipends and asylum interviews. I type each name into a spreadsheet, the many forms of Ebrahim and Mohammad, Ali and Safir. Repeating their names and returning their cards is a lesson for me, reciting each one, like a radio broadcast, ringing the planet with call letters that tie us all together anonymously, just by the act of repetition.

Finally, on my first day, without a lesson plan, I have the advanced English class. One student, a sharp and handsome Afghan named A___, studies me with penetration. He’d easily play a CEO or a fashion model with his black-framed glasses and buttoned down shirt. The class is an improvisation and his conversation is fluid – though he cannot write much. I stumble into talk of stereotypes and cliches. How do we see each other, not knowing? What assumptions do we make? Maybe he’ll encounter this or already has. Maybe I want him to wonder who I really am. It seems inevitable to talk about family and siblings. He is number two like me, but with seven brothers and sisters. I muse about the difference between immediate family and extended family, but quickly realize that his home family would likely include uncles and grandparents, unlike the suburban nuclear family of the west.

We skirt these details respectfully. In our next lesson I ask him to write a few sentences in Farsi in the back of my sketchbook.

“I am not a refugee” he writes, the right-to-left slanting Arabic, the fascinating squiggle.

“So,” I say, “Write a sentence about what you are, not what you are not.”

“I am human. I am humanity.”

I think perhaps we can find some quotes to translate and I show him my sketchbook with the journal entries. “I used to write,” he says, “Until I changed my phone.” But he finds some words from months ago and reads them to me in English. I cannot quote him but he describes waiting each day for a decision, an interview. He encounters some old pictures of his brothers and grandparents and his “eyes get wet.” His waiting and his hopes bely his composure. He talks of faith and prayers and the slow passage of time. I had almost failed to see these precarious feelings just beneath this placid manners.

“You are amazing.” He says as we shake hands to close the day, and I can only look back at him in awe.

One of the Swiss girls has a birthday party on her rooftop overlooking the harbor that night. I arrive with a four-dollar bottle of wine into a room full of Afghans, and wonder if I should hide the bottle. Anyway there are Germans and there will be drinking. Ivan the Catalan yoga instructor and Simeon the science educator from Holland, Timmins the boisterous, Majid the tall, sharp nosed Afghan who brays to the music and three or four younger Afghans who quickly form a dance circle with twisting steps and spinning palms. Their dance is completely self-aware but without a trace of self-consciousness. Their expressions are inborn delight and something like flirtation. The young German girls are in the mix and even I am pulled in for a moment. Arabic dance music is as infectious as Motown, or more so.

The next morning as we wait for the gate, Valentin strums a guitar and we sing “House of the Rising Sun” and a Ray Charles song, a little gravelly funk that kicks up the day. The waiting group cheers.

Wednesday–Thursday

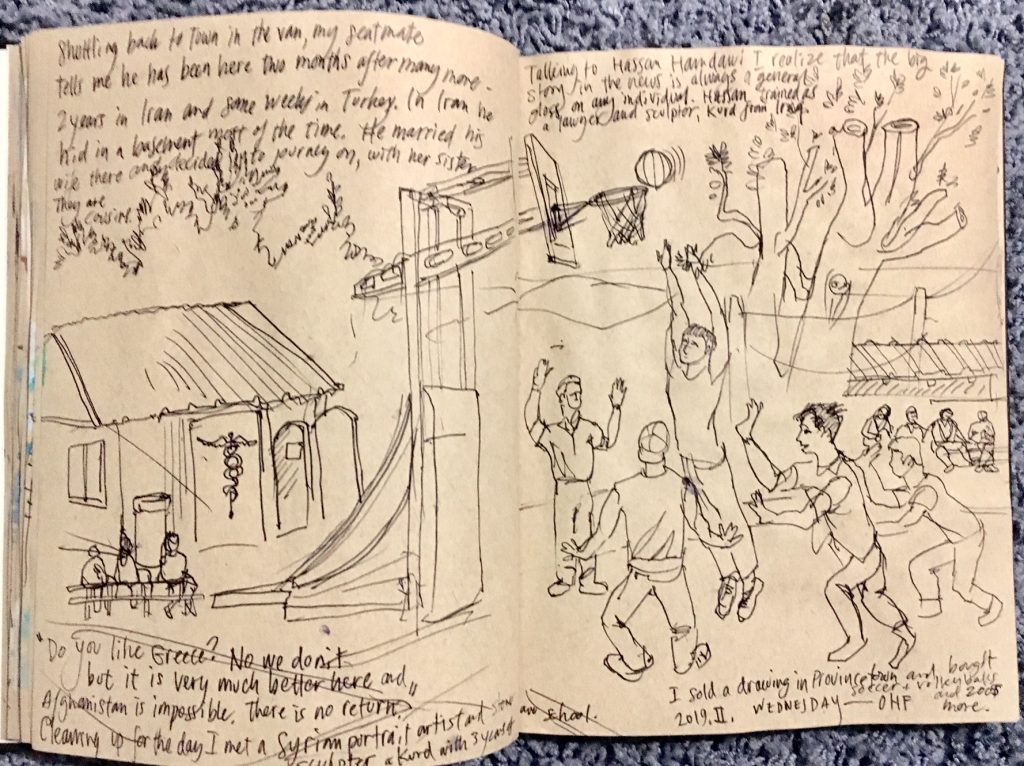

Constantly, especially in the kitchen shed, there is Arabic dance music and some mixy mixy tracks that are familiar to the twenty-somethings, Euros and Arabs alike. An essential groove slides around the place. Any lull and there is a football circle, passing, doing stunts with the ball. Some women join in but the footwork is universal among Afghans, Germans, Israelis and the Catalan. Children run in little gangs or clear a space and spar. I bought a few new soccer balls and a “Hello Kitty” kickball and I get a charge out of seeing them riccochet. There are 15 or 20 long term migrant helpers, a mix of Africans and Afghans. These guys are gymrats with cropped sides and slicked back locks, immaculate and somewhat conspiratorial but cracking smiles and fist bumps with me and everyone as if they mean it. Always there, the helper security team, yet never evident, they police the lunch lines and the barber shop and suddenly appear, knowing when a child’s cry is real. The gym is an open shelter adorned with a half-finished male torso painted on plywood and an incongruous pommel horse standing by (perhaps someone besides me knows what it’s for). As soon as the gates are unlocked, someone is doing speed pull-ups or furiously pumping a barbell. This intensity is suggestive of a pent-up energy that is either hormonal or a by-product of the caged life of the camps. I see few older men at OHF. The migrant road may have filtered them out or the long daily walk from Moria Camp. I’m tempted by a stereotype of Mediterranean village life: the women work til death while the men retire to smoking and backgammon after 50. Either way, I am surrounded by youth. I get to speak to the women who appear in my English classes, in the minority but up front and first to answer every question. War is another filter and in one class we are running through sentences about family. I obtusely strive to explain the relationship of grandparents to grandchildren. “No,” he says, “No.” Blankly. Finally another man says, “Taliban, Daesh.” His grandparents are gone. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. It’s OK. And he is eager to to read the next lesson: “Ask Anka if she is a nurse. No, she is not a nurse.” “We are Canadian.”

And I quickly flip open my pocket atlas to show that Canada is a country in North America.

Today I help pass out the lunch. The kitchen helpers ladle and pass bowls with spoons through the window and we hand them to the three lines: “babies” in the middle line, women to the right and the much longer line of men to the left. Security helpers tell us who to serve, on the lookout for kids that changed their shirts to get a second bowl. This is the day when the stew contains chicken, held secret so that the camp isn’t swamped with new visitors. I pass bowls to the women’s line with both hands and look at each of them in the eye until they smile and disappear to a bench. The stew is really excellent. I’m trying the discipline of eating only what they eat each day and I have begun to remember genuine hunger.

Muhammad sits in the volunteer office most of the day or ranges around the hall collecting used plates and bowls, interpreting and troubleshooting. He is almost singular here in how he dresses: full shalwar kameez or dishdasha in turquoise blue, maybe with a scarf. No one remarks on this as ostentation and his modest grin is anything but pompous and these differences go unnoticed. He shows some photos of his grandmother’s house which looked like a grand carpeted palace. Some puzzles are yet to be explained such as how little show of prayer goes on here. There is a row of rugs behind the Mobile Doc clinic and a faucet-fountain for washing — which I noticed as one of the security helpers made the distinctive motion of rubbing his gums with water, one of the 6 parts of the body that must be clean for prayer. There is no deference to an Islamic clock here and the European volunteers have dismissive views of religion. While the do-gooders are mostly atheists, the migrants are likely believers but moving in the rhythm of this slightly anarchist community.

More than once OHF has resonated like a major chord to the echoes of my summer camp of 50 years ago, with its recreation and banter and communal meals.

Today in the office Jan and Ivan and I examine the multicolored stamps on a child’s identity card, red is rejection and multiple stamps means they’ve been appealing. If asylum is denied, the next step is deportation — whenever the wheels turn that far. Meanwhile, stipends and services stop, and going underground seems an option that will prolong the journey onward. Every migrant who speaks to me says they can never go back.

Week 2, Monday

We stood outside in the raw wind, measuring the concrete sports area by pacing, one meter per step, to scale a map at five degrees per meter, latitude and longitude, our wacky project idea. Myself, the Germans, the Swiss, the French, we are all delighted to be making something on the grounds of the migrant center. Will it mean anything to the Afghans, Iraqis and Africans? We are here to share and not be timid. Being this close to people that are bounded by rules that exclude them, spending our days laughing and eating and sharing coffees and volleyball, I’m doubtful what I can give them and how we can be equals, share the same lens on the world. We don’t, we perhaps cannot. I just don’t know. I did a portrait in blue pencil of H___, the Kurdish barber from Kurkuk, Kurdistan, Iraq. We waited for the van together this morning in the biting cold harbor wind and I gave it to him, an invitation to tell me more about himself. One thing he didn’t tell me: that his mother is home in Iraq waiting for a kidney transplant and his siblings are spread out across Europe. Iraq is too dangerous for him to return. He has a residence permit but can’t leave Greece or travel to Europe — like most of the inhabitants of Moria refugee camp.

Teaching English conversation to some of the long-term residents of the camp, I pulled out a hand lettered version of Mary Oliver’s “A Summer Day,” a lyric to the blessings of idleness through the eyes of a grasshopper with its sharp note of loss and the epigram that trumpets the privilege of those of us free enough to have aspirations: “What will you do with your one wild and precious life?” Can’t help but wonder if this is callow or a thread of hope. We were supposed to talk about perfect tense conjugations, the ongoing past and future: as we were running and playing last year and will continue to run and play in the next. The next tense is the conditional: if I eat I will not be hungry, if I sleep I will not be tired. If I was home I would have been happy.

I can’t stop this kind of conjugation.

A panoramic family photo falls out of my sketchbook, a joyful moment in a somber gathering, a picnic with 40 people around a tree where my brother’s ashes are buried. The vision of connection to nieces and in-laws, the extended belonging. I wonder if a traditional culture like Afghanistan’s would be richer in these threads than our suburban diaspora of choice. Or if my particular family constellation might mock the family rending that has lead these travelers here.

Tonight at the Cafe Pi some Germans and I calculate the latitude and longitude of our mapping project to be painted across 12 meters of playground, the coastlines and boundaries around the Mediterranean. We consider the projection, curving the great circles of longitude to give it a global feel. The debate that ensues, whether we should include all the political boundaries and the origin countries of the migrants. The others worry and insist that national boundaries in the Middle East carry all the baggage of imperial decisions that have been oppressing minorities since the end of WWII. As a cartographer I don’t believe in editing maps though I would prefer to show the landscape over the politics. A map that only shows the “stable” boundaries of Europe and turns Syria and Palestine into vague clouds seems disrespectful of the realities people face. Many walked around these borders hiding in the woods. Many were shoved back across them by border police. I’d rather do a mural of the Easter Bunny and his friends than a soft focus map. But they enjoy the debate and chew on it, drawing in others from around the cafe. I can only despair and find a diplomatic retreat.

Tomorrow we patch concrete and draw lines on the basketball and volleyball courts. Step by step.

Read more about contemporary Europe in Michigan Quarterly Review’s Fall 2019 Special issue.