Jiwone Lee is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Seoul, in the Graduate School of Design, Illustration Department.

A pencil. A piece of wood encasing a graphite core that can draw in a thousand hues of grey and black. The memory of the first attempt at writing, the hardness of the wood between uncertain fingers, the exertion of small force on the paper and finally, carefully drawn marks of different thicknesses and angles. Joanna Concejo’s many works evoke this forgotten memory of our graphite past.

Joanna Concejo is a Polish illustrator who lives in France. She has worked as a ceramic artist and also done installation works, but since her illustrations got selected at the Illustrators of the year awards at Bologna Children’s Book Fair and won the “AbraCalabria” prize in Calabria Incantata International Illustration Competition in 2004, she has been devoted to book illustrations. Working with Italian (Toppipitori), French (Poisson Soluble Motus, Rouergue, Casterman, Editions Notari), Spanish (OQO Editora), Korean (BIR), and Polish (Wydawnictwo Format) Publishing houses, she has published more than 19 picture books so far. Her picture book, Zgubiona Dusza (The Lost Soul)[1] won the Bologna Ragazzi Award Special Mention in 2018.

Zgubiona Dusza (The Lost Soul) is a two-page fairytale written by the award-winning Polish novelist, Olga Tokarczuk. In this story, a man worked so hard and relentlessly that he left his soul somewhere behind him. After consulting with a wise doctor, he decided to wait for his soul to come find him again in a peaceful place and they eventually got reunited. Most of the text is actually printed on two pages of the book at the beginning after a long prelude of image-only pages, and the rest of the text appears just before the end of the book with a grand finale of image-only pages. Illustrations tell this story with more detail and specificity – for example, we come to know that the man’s soul has the form of a little girl, unchanged over time. We travel with the man’s reminiscences and we see brief moments of a boy admiring a sunset on a train and a dancing couple in a Polish countryside. Seeing those images, readers recall the story they read in previous pages and give these silent illustrations their own narrative. This book’s unique construction makes this parallel narration possible, which states the autonomy and the confidence of the artist-illustrator as a co-creator of the book and the book as an art object.

Joanna Concejo’s earlier picture books, Il Signor Nessuno(Mr. Nobody),[2] L’Angelo delle Scarpe(The Shoes Angel)[3] already reveal characteristic traits of her art: the use of the recycled paper, pencil, and color pencils, imaginative and poetic imagery – for example, upon seeing an angel on the balcony, the boy protagonist’s belly changes into a birdcage full of colorful butterflies in L’Angelo delle Scarpe—and totally unbound characters sometimes appear out of nowhere (like the huge, room-sized bird that is completely drawn in pencil in the boy protagonist’s house). Joanna Concejo is a strong believer that illustration should not be a literal depiction of a story. In her book, the illustrations always reach beyond the text.

When I illustrate a book, I always think of writing it in another way, with imagery. I do not think of illustration as being in service to the text; it should never be. What’s interesting is creating a dialog between the text and images so that the two can—when meeting in the space of a book—tell something new and unexpected. They can open new pathways and new possibilities for interpretation. Let that meeting surprise, disturb, worry, and question. I think that this is only possible when text and images remain free and beautiful in their differences. When they are lovingly distinct.[4]

However, the dialogue created between the text and the image can be really diverse, and the books that Joanna Concejo illustrates can be read many ways as readers may derive various interpretations. 빨간 모자(Little Red Riding Hood)[5]was published in Korea by leading children’s book publisher Bir in their series of World Classics. However, what came out of Joanna Concejo’s intense pencil drawings are far removed from either Charles Perrault’s cautionary tale or the Brothers Grimm’s later retelling of the story.

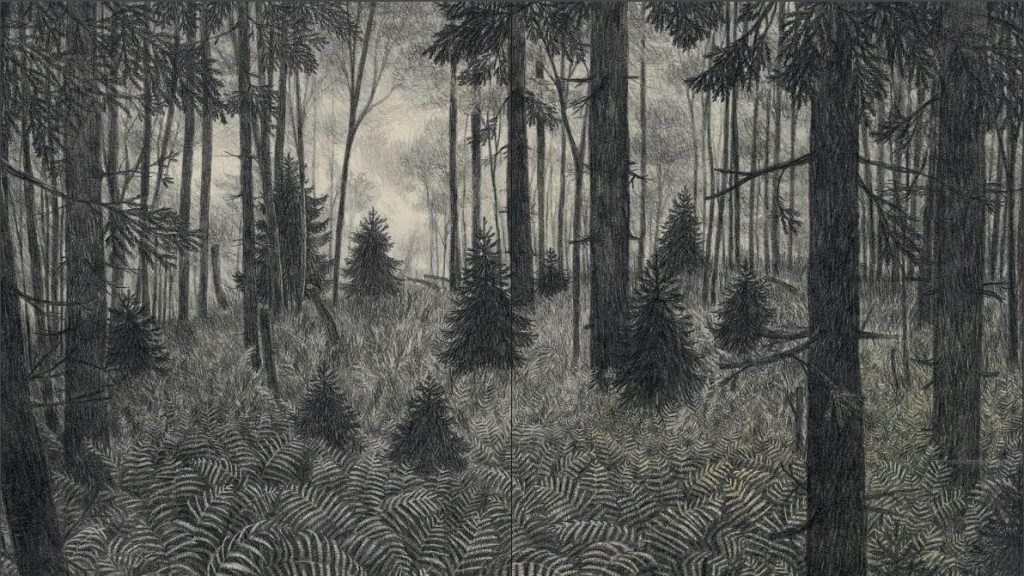

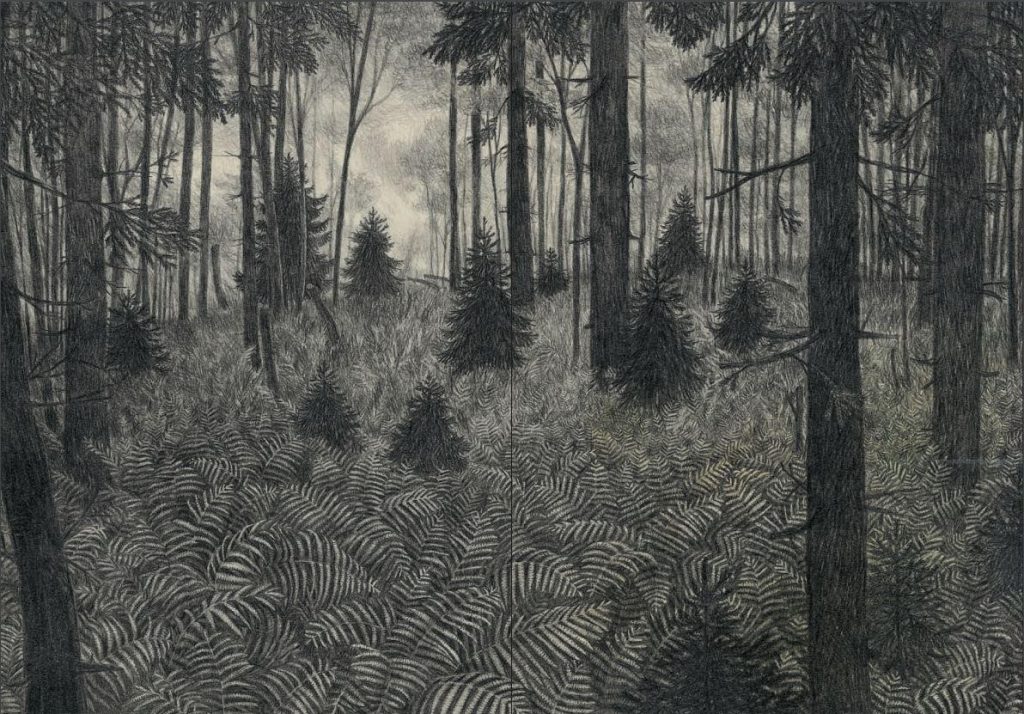

Joanna says that “Little Red Riding Hood” was never her favorite fairy tale, but she closely associates it with her childhood spent in the densely forested countryside of Poland. Hearing the story from her grandmother, young Joanna believed that this was a real story about a real neighborhood girl who was stupid enough to have gotten herself in trouble. The realization of what this story describes came to her much later.[6] Joanna Concejo’s Little Red Riding Hood illustrations demonstrate these conflicting impressions, mingled with her own childhood memories. The directness of her approach is seen throughout the book, mostly through evocative forest scenery from her homeland. The portrayal of a gloomy forest filled with ominously glistening fern foliage in the dark and hundreds of conifers all alive with needle leaves were drawn solely in pencil, thus preserving the heavy and metallic sheer of the graphite in intricate strokes. To invite readers to her own retelling of Little Red Riding Hood, Joanna cleverly decorated the book’s cover with folk embroidery motifs from her homeland Kaszuby. The message is both hidden and explicit. It is a manifestation of her very close association with the story and a symbol expressing her longing for her hometown; however, the confession remains hidden to readers unaware of her history. Meanwhile, the strong love plot that she successfully wove into the existing story cannot be ignored. The little girl and the hairy wolf are attracted to one another, yet they remain faithful to their own worlds in the end. The wolf perishes and the girl walks into the forest and with all her experiences, she is now another person, a woman. The book’s Korean Publisher, BIR, gave Joanna Concejo complete freedom to interpret this well-known tale in her own way and to construct the book and the pages as she wanted. The very unusual long prelude illustrations preceding the text snatch the readers and move them to the dark forest of Kaszuby even before readers can take their stance on this familiar story of a girl and wolf. The picture book—once thought to be made exclusively for children—breaks free of its original domain. Joanna Concejo knows its unique power of combining images and text very well and her images roam freely between borders of adults’ and children’s imagination.

When people ask me what I do, it is somewhat hard for me to answer because just saying that am an illustrator is not really right. I could say that I am an artist? That label does not suit me. I think that I simply express certain things that dwell in me, that are important to me, that make my heart sing and make me feel alive. I do this through drawing. I just draw.[7]

For each of her picture books, there are volumes of preparation sketches that trace how her ideas and inspiration developed. The drawing process is incessant, free, and unrestrained. For both drawing and originals, she adapts the simplest of materials, paper and pencils. Her final works are done mostly on “found” paper that has already been used once, recycled, often already faded, papers that once held their own story.

I like to draw on old pieces of paper that I pick up all the time.[…] They have traces of time, tears, stains, and folds. Light has either yellowed, or in contrast, paled them…[…]I like to inscribe myself in that continuum, in that journey through time; it inspires me, reassures me. While drawing, I feel as though I am doing no more than pulling out pages that are already there, even if they were not visible. It is as if the sheets are talking to me, showing me what they’re hiding.

Joanna Concejo’s illustration works hugely inspire many young illustrators. As an illustrator, she has found a way to be an independent artist besides the existing stories. She tells stories of her own, adds other sub-stories, edits, and redirects. With existing stories, she is more like a mighty film director than an illustrator as we understand the term. All her actors, mise-en-scenes, and staff, both human and nonhuman, are under the complete control of her pencils. Her stories are complex, they sometimes record her private memories, bring up unknown (to most readers) customs and cultural contexts and sometimes intentionally mis-lead readers to go deep into their own stories. Obviously, the readers that she addresses are not only children.

[1]Olga Tokarczuk, Zgubiona Dusza, Wydawnictwo Format, 2017.

[2]Joanna ConcejoIl signor Nessuno, Topipittori, 2008.

[3]Giovanna Zoboli, L’Angelo delle scarpe, Topipittori, 2009.

[4]Joanna Concejo’s interview with Picturebookmakers blog. (https://blog.picturebookmakers.com/post/113865162521/joanna-concejo)

[5]김미혜 (Kim, Mihye), 빨간모자(Little Red Riding Hood), BIR, 2014.

[6]From the reader’s meeting with Joanna Concejo. National Library for Children and Young Adults, Seoul, Korea, December 7th, 2017.

[7]Joanna Concejo’s interview with Picturebookmakers blog. (https://blog.picturebookmakers.com/post/113865162521/joanna-concejo)

You can purchase a copy of MQR’s Fall 2019 Europe Issue here.