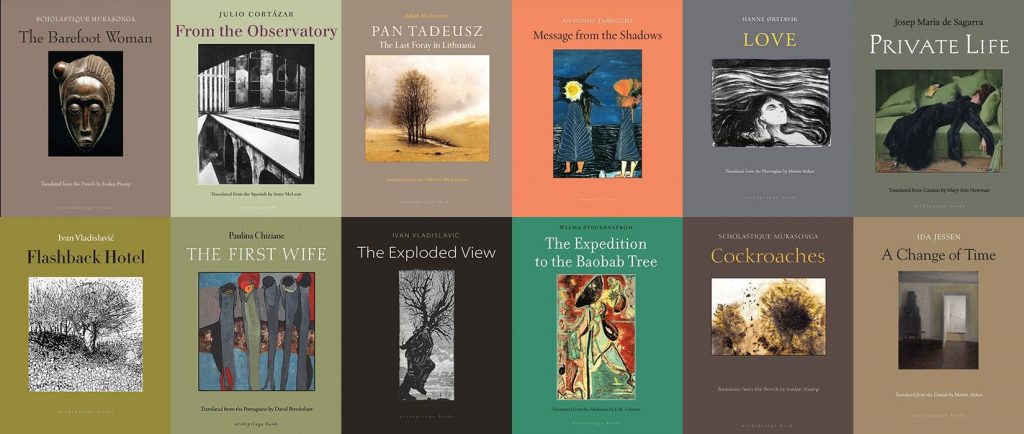

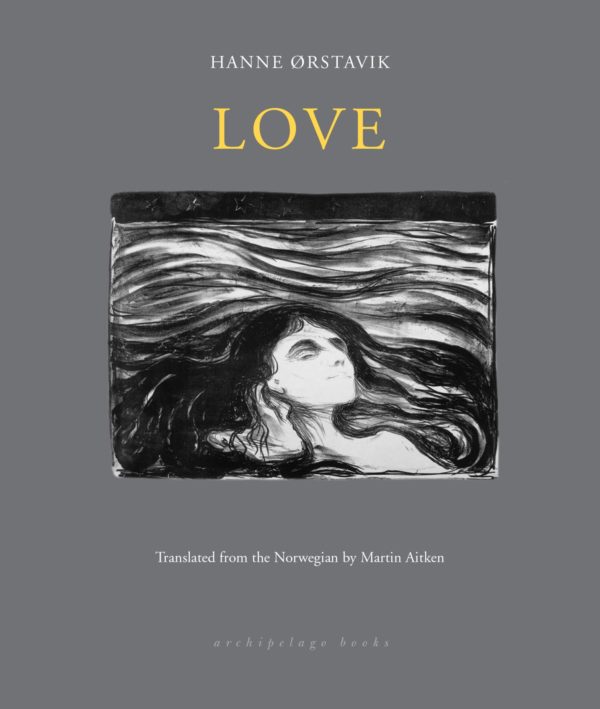

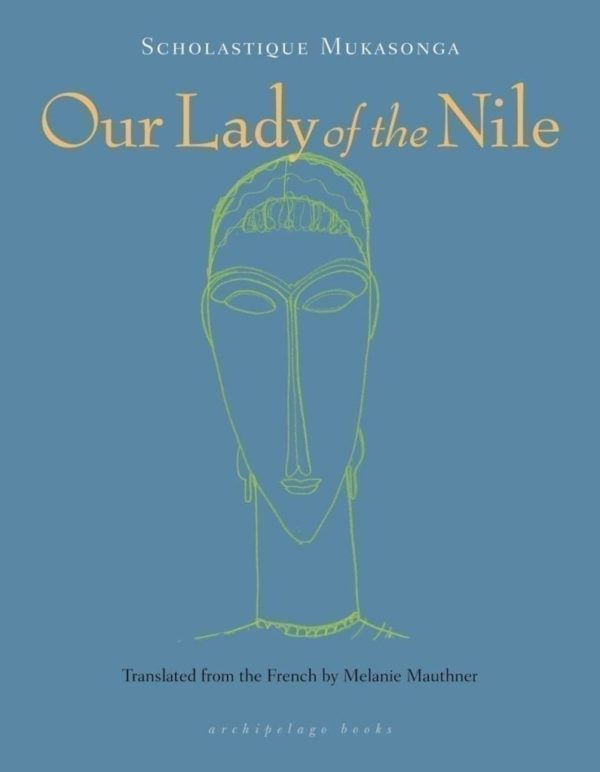

Brooklyn-based Archipelago Books is a not-for-profit press devoted to publishing translations of classic and contemporary world literature. Since Jill Schoolman first founded Archipelago in 2003, the press has produced close to 200 books from more than thirty-five languages. Their award-winning titles include Hanne Ørstavik’s Love, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, Scholastique Mukasonga’s Our Lady of the Nile, Antonio Tabucchi’s For Isabel: A Mandala, and more.

In this latest installment of our Small Press Series for MQR Online, Archipelago’s editorial and development associate Emma Raddatz shares the ins and outs of working at a small press, why translations are so necessary in the American literary landscape, and recommends upcoming titles from the Archipelago catalogue.

CF: Editorially speaking, what makes a book an Archipelago book? What are its necessary ingredients?

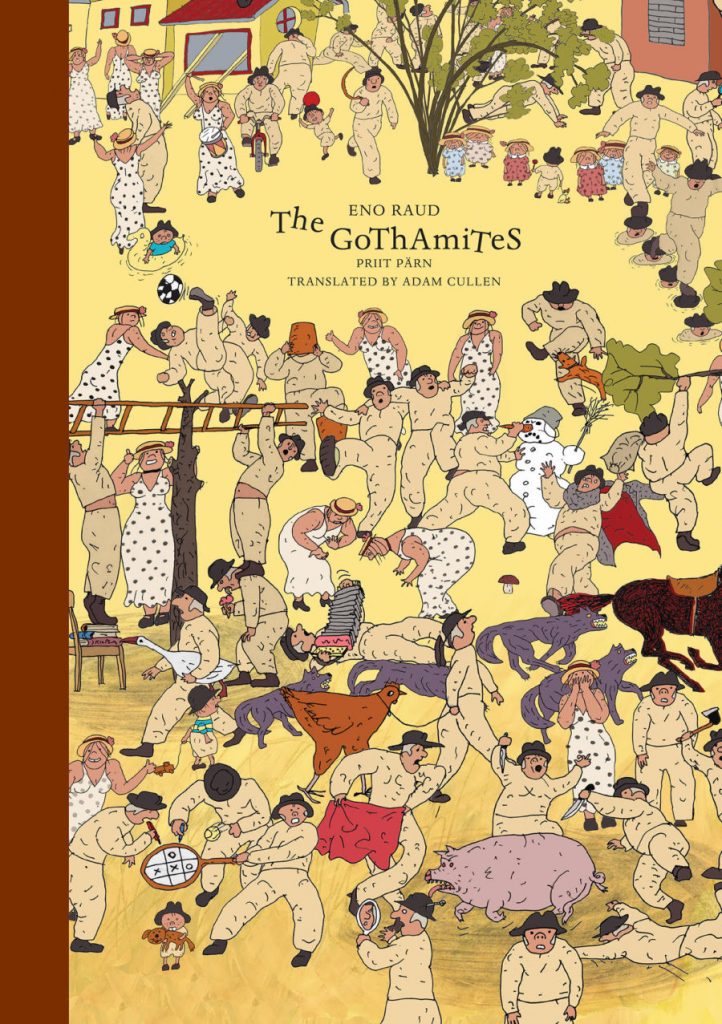

ER: Archipelago has quite an expansive and eclectic list. We look for works that are saying something urgent and vital in a very distinctive way. Titles on our list often drift between poetry and prose; the lyric or the tight, crystalline writing characteristic of Hanne Ørstavik’s Love. We also seek out languages that haven’t been translated into English very much. We’re publishing one of the first Kurdish novels into English, by Bachtyar Ali, and we just published an Estonian picture book called The Gothamites.

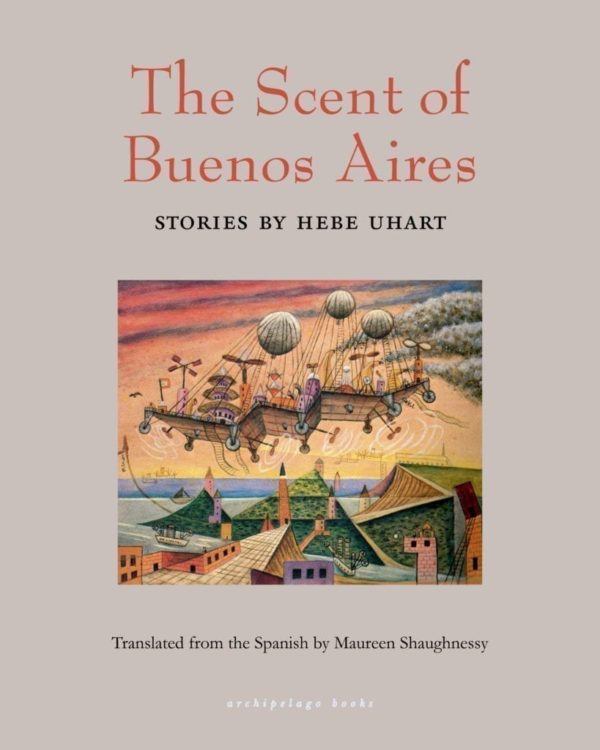

I think a blurb about one of our forthcoming authors captures our mission quite nicely. Haroldo Conti said that Hebe Uhart’s writing “reveals a unique reality, or the fact that she, herself, is a unique and different reality.” We’re looking for books that create new worlds and realities through language.

What does a functioning day at the office look like for you? What are the joys and hardships of being a not-for-profit press?

Archipelago is made up of three full-time employees: our publisher & founder Jill Schoolman, our publicist Sarah Gale, myself, and one editor named Anna Schwab. We also have a group of wonderful interns each season. Because we’re an uncommonly small operation, we all have to wear many different hats each day. I’m often working with designers, booksellers, printers, or grant-administrators in the same morning. I think this is true of most small presses—we don’t have such strict departments or titles, and we’re always collaborating. It makes office life infinitely more interesting.

Can you tell us about Archipelago’s relationship with bookstores and other literary organizations?

Booksellers have been really fantastic with our books. Many independent shops have been making initiatives to sell and promote more international literature, either through dedicated translation sections on their shelves or through bilingual and translation-focused reading series. Brookline Booksmith in Massachusetts has a fantastic series run by Shuchi Saraswat on migration, displacement, exile, and translation. Our author Karthika Naïr will be reading and launching her book Until the Lions there in early December. Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum is also doing amazing work with translated literature, as well as providing sanctuary to endangered international authors.

How does a translation manuscript land on your desk? What is your submission process?

Books find us in a few different ways. Translators often pitch projects to us, and then we read samples or fully translated manuscripts. We care deeply about treating translators as artists, so we communicate directly with translators and involve them in all stages of the editorial process. We also sometimes commission 20-50 page samples of a book or author’s work that we’re really excited about. We do have strong relationships with international agents and read several agented submissions throughout the year. We also occasionally participate in international fellowship programs and book fairs. I most recently attended the Istanbul Fellowship and the Korean Literature showcase (hosted by LTI Korea) in the hopes of learning about those books that are most culturally vital and formative in these countries. We don’t have a formal reading period, but we’re all constantly reading and talking about submissions together.

What do you personally love about reading translations of international literature?

I feel like translations unsettle one’s normative notions of place and language. It’s a tricky balance of accommodating an English-speaking ear, while not normalizing the parts of a writer’s language that are deeply rooted in a place or a way of life. I’m drawn to the breaks in language that this problem creates— the books that invite certain readers in while rattling others—when English is suddenly sprinkled with the original language, or with the unique rhythms or cadences of the source.

Every book published at Archipelago has a deliciously satisfying, minimalist design. How did the press settle on its signature style?

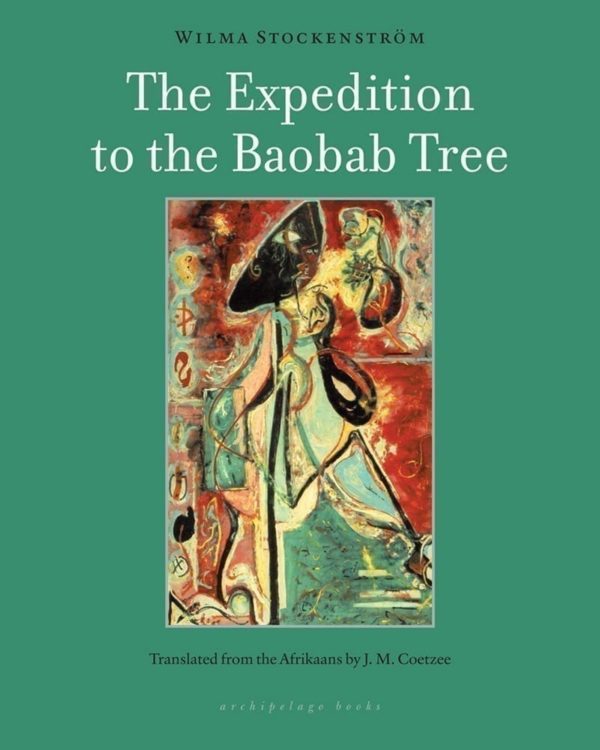

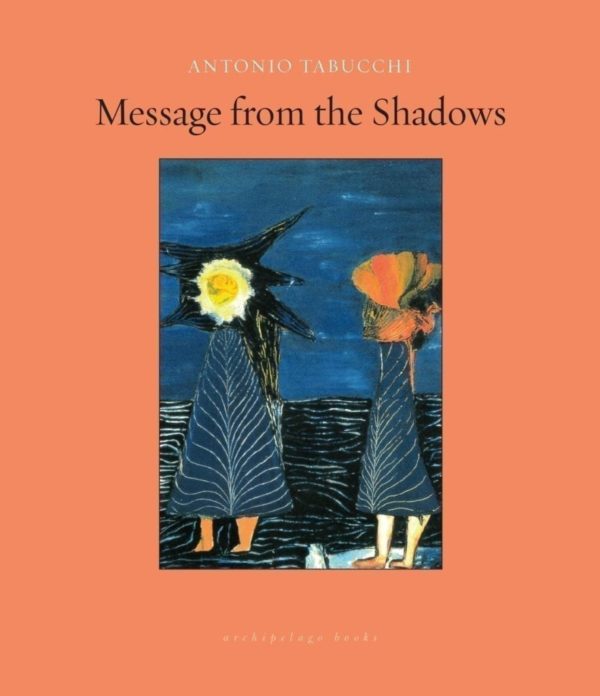

The design was created by Jill and our wonderful designer emeritus, David Bullen. They wanted Archipelago’s books to feel like a real collection of translated literature, to encourage readers to build more international libraries over time. The colors tend to be designed with warm earth tones, but occasionally they are more striking. Wilma Stockenström’s The Expedition to the Baobab Tree, Antonio Tabucchi’s Message from the Shadows, or Scholastique Mukasonga’s Our Lady of the Nile, are a few of these bright, beam-like covers. We also care a lot about paper quality and stock, so all of our books have laid paper covers with flaps and a nice, heavy text stock.

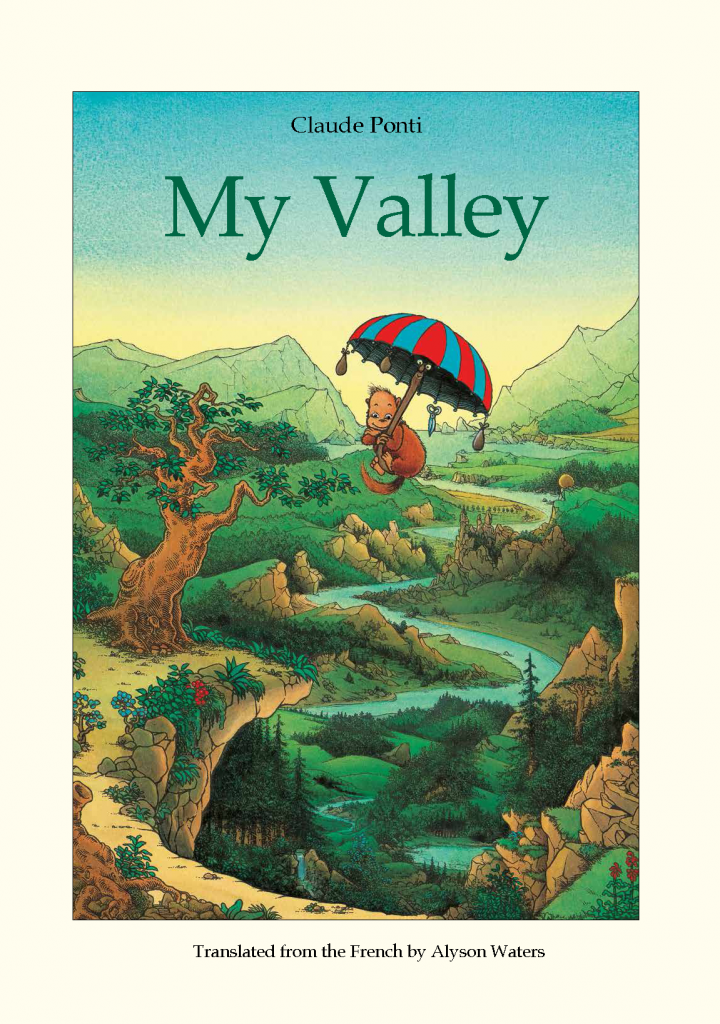

In Spring 2017, Archipelago released its first title for its imprint of international children’s picture books, Elsewhere Editions. How did the idea for this new venture come about?

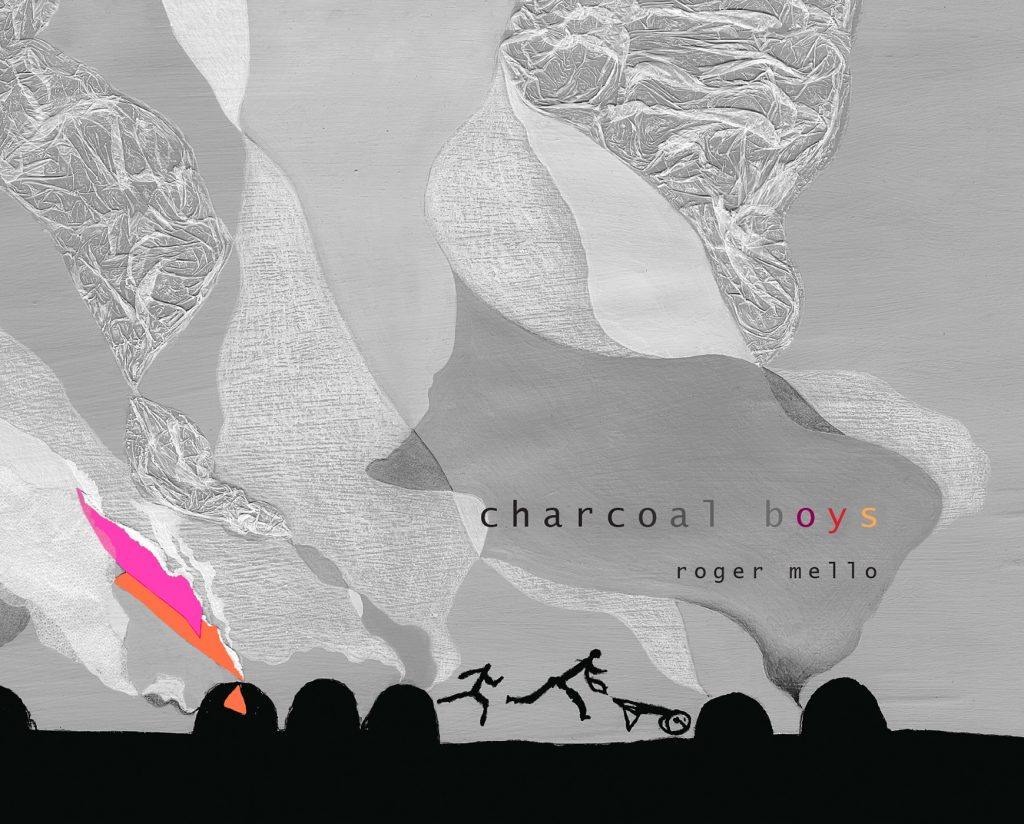

Thank you for asking about this! We see Elsewhere as a natural and essential extension of Archipelago’s mission. From meeting with parents, teachers, librarians, and kids, we’ve found that people are really ready for more inclusive and innovative children’s literature. We launched the imprint in 2017 with French illustrator and author Claude Ponti’s visionary book My Valley, translated by Alyson Water. This 11 x 15 book is really kind of cinematic—it completely envelops you and drops you into the strange and wonderful world of Ponti’s Twims (tiny, extremely lovable, monkey-like creatures). We’ve also published several books by Roger Mello, winner of the 2014 Hans Christian Andersen Award. He creates a constant effect of movement in his illustrations, along with complex and delightfully boggling turns of phrase and thought. His forthcoming Charcoal Boys is a sensitive portrait of a young boy working in Brazil’s coal mines. It follows a tiny wasp who flies alongside the boy throughout his day. Our hope is that Elsewhere encourages people to start reading more internationally and inclusively at a young age.

Looking ahead, what are your goals for Archipelago Books in the coming years?

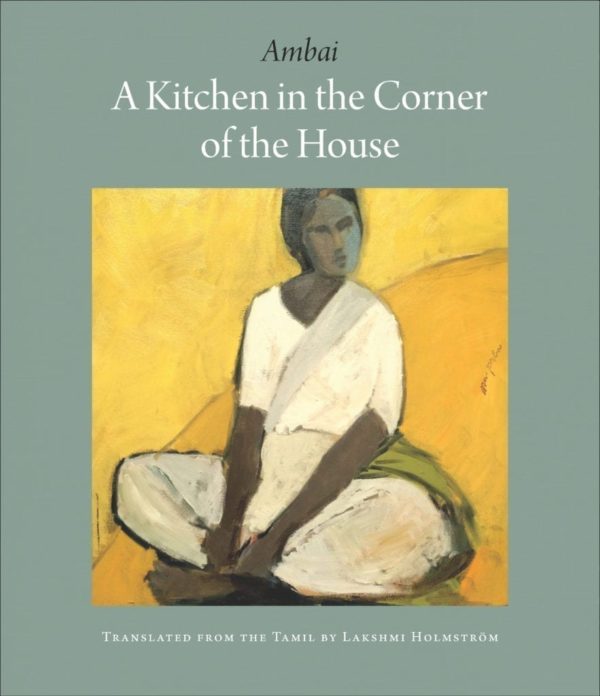

I’m really excited for a series of Indian literature by women that we’ve quietly launched. We’ll be publishing a groundbreaking feminist Tamil author, who writes under the pen name Ambai, this September. This short-story collection is called A Kitchen in the Corner of the House, and it’s all about the ways that women stretch and reinvent a world that persistently oppresses them. We’re also publishing Karthika Naïr’s Until the Lions this fall. It’s this formally daring reworking of the Mahabharata, and it reads like a fiery blast of poetic expression. Our list has always been political (recently we were donating books to an event around the theme of “exile,” and found that we had over 10 political exiles in our office to choose from), but I think it’s also moving toward greater intersectionality through efforts like our Indian series.

Can you recommend a few recently published or forthcoming Archipelago titles we should keep on our radar?

Out of our recently published, one of my favorites is Ida Jessen’s A Change of Time. Ida is a Danish novelist, and this is only her second book to be translated into English. It’s a wonderful book about grief, memory, and the possibility of finding new parts of oneself later in life. In the first pages, the narrator discovers an old journal and decides to reread and fill its pages again. Ida’s language is quietly precise, but there’s tension bristling just beneath the surface. The poet Anne Michaels called it a book of “tender restraint,” which describes it so perfectly.

We’re also really excited in the office about a collection of short stories by the Argentine writer Hebe Uhart. She’s one of these authors that we’re shocked hasn’t been translated before. She writes just as she watches, carefully observing and tuning her thoughts. One of my favorite lines reads, “Now that I am a bit of a witch I can see my rude streak. I eat directly from the pot, I gobble up my food.” Her stories make you see plants, small towns, or the witchy parts of oneself in new ways, marbled with humor and a kind of awe that is all her own.

What books are in your personal TBR stack?

I just found a used copy of Shani Mootoo’s Cereus Blooms at Night. She’s a Trinidadian-Canadian writer who I’ve heard is fantastic. I also found a copy of Erna Brodber’s The World is a High Hill in Fort Greene’s The Center for Fiction. Her book Myal is a small masterpiece, but I’ve never seen this book of hers.

Cover image courtesy of Archipelago Books.