We hear the trunks of beech trees described as pillars that look like the legs of elephants. We hear them called autograph trees, because they hold the wounds made by solipsistic children (or by the poets visiting Lady Gregory at Coole Park) who cut their initials into that smooth gray skin. That is all most of us learn, and sometimes it used to feel like enough.

That was not enough for C. D. Wright. In the years before her sudden and unexpected death in 2016, Wright was fascinated with the American beech (Fagus grandifolia) and the members of its family. She tells us early on that the “American beech … is not the priority here, only because it is rarely among the beeches I see daily where I live in southern New England. Their masses having been greatly diminished since settlers grasped that they grew in soil good for farming.” Perhaps it was that sense of loss that sent her out searching for different kinds of beech trees, that sent her rooting around in the old books collecting lore and the attempts at early science, that forced her to learn everything she could about these trees.

At first glance, Casting Deep Shade is a commonplace book of all this information. She gathers it together in small fragments, seldom more than a fraction of a page long, that appear randomly organized. It is a process recognizable from her earlier work. Although documentary impulses were in her work right from the beginning, after her One With Others from 2010, which combined newspaper reports and interviews with her own verse, to explore a moment in the history of the Civil Rights movement, Wright’s readers expected that combination of research, documentation, and poetry. It was her method, one that set her apart from almost every other poet working.

As we read further into this collection of information, it seems as if Wright has removed herself even further from the page than she had in earlier work. It is only as the book begins to grow on the reader that it becomes clear that there is an organizing poetic impulse behind it. Wright was always fascinated with the words for things, and here the words having to do with the botany and history of beech trees start taking over. There are not only the names of the trees themselves, but all the words for the parts of the tree – lamina, midribs, lenticels– and the larger geographies of trees – copse, grove, coppice. She relishes words like mast,which it seems we should know but the meaning wasn’t quite clear until Wright stresses it (it is the nuts that fall in certain years, but not every year, and make a kind of carpet on the floor of the forest). And she gives us a word for a phenomenon we know but never named. In Michigan winters we see the withered yellow leaves of young beech trees quivering just above the snow until spring. These are called marcescent, Wright teaches us, and the leaves aren’t pushed off until the new buds are formed in the spring. The poet is teaching me things about my own forest that I didn’t know despite my efforts to pay attention!

And between or out of the pockets of information, the poetry arises:

The littlest flowers are unisexual.

It is a Stone Age tree.

An Iron Age tree.

It is an Ice Age tree. According to the pollen record.

Preglacial fossil remains have been found.

There are ages in between.

The evidence is in the peat.

Not introduced by Romans as formerly thought.

To Caesar’s claims, pay no mind. (Hence the phrase: full of baloney.)

In that last sentence on the list, which has gone a long ways from the first one, there is that unmistakable twist of C. D. Wright’s humor, another element in much of her work. A few pages earlier, she writes (incidentally about the trees that were filmed a time or two in Game of Thrones), “In County Antrim, Northern Ireland, there is a landmark tunnel of beeches, the Dark Hedges, planted in the mid-18th century by the Stuart family. Other references list them as 300 years old. Pictures of them would make a romantic out of a rock.” That last sentence is a signature move by the poet C. D. Wright, and goes a long way to explaining the appeal of her unique voice and vision.

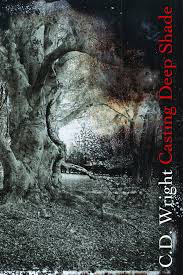

Casting Deep Shade is a big book, over 250 pages long, with notes and bibliographies. It is bound in a kind of folding box, in the world of contemporary poetry comparable only to Anne Carson’s Nox, although I think Wright or her publisher might have been thinking more about a specimen box, or even the notebook of a field biologist. Old maps are in here, and eighteenth century illustrations. There are photographs that Wright took herself on her phone; she tells us that with a certain amount of glee. And then there are the photographs by Denny Moers, studied photos of mythic looking old beeches manipulated by dark room techniques and given their own high quality paper to keep their shine. By the end, all of this has come together through a complex web of associations the readers don’t even have to realize they are making. Beech trees have suddenly become part of our shared imagination in a way that comes only through hard study or a memorable poem.

C.D. Wright’s final book, Casting Deep Shade, is available from Copper Canyon Press.