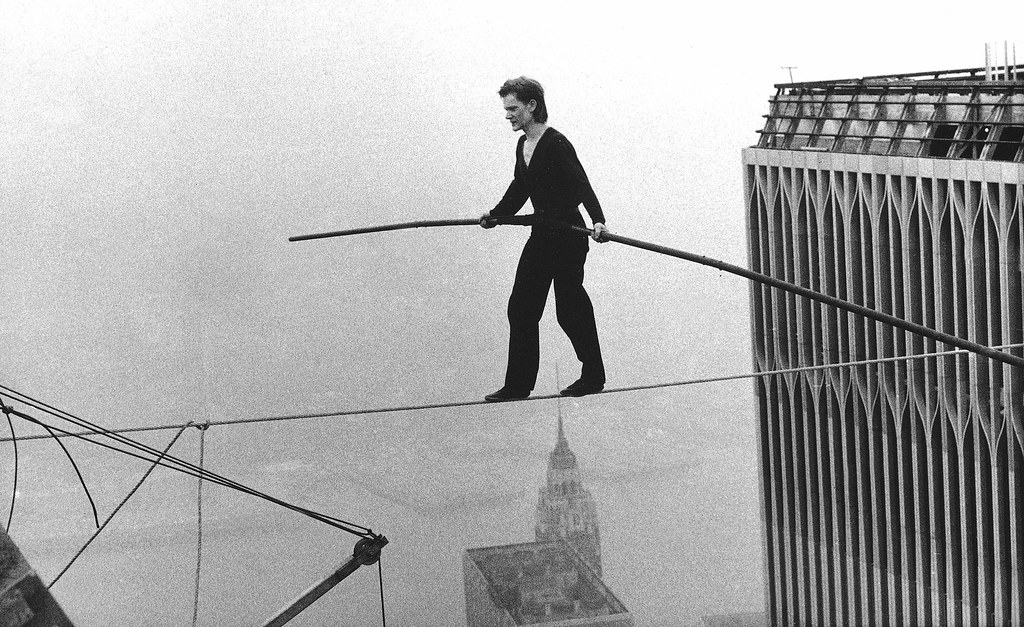

The excellent 2008 film Man on Wire has many noteworthy scenes—as it should, given that the movie won a BAFTA for Outstanding British Film and an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, among others—but one of the most instructive is a scene relatively early on, when the filmmakers are interviewing Philippe Petit.

Perhaps the most famous and talented high-wire artist on earth, Petit is best known for his walk between the twin towers of the World Trade Center during the morning of August 7, 1974, which is the subject of Man on Wire. In the scene in question, Petit, an exuberant gesture of a Frenchman, eagerly describes the stakes imposed by the art of high wire-walking: “If I die, what a beautiful death. To die in the…, in the exercise of your passion.”

In the film, Petit’s pop-eyed bonhomie regarding the seriousness of his art adds an air of lunatic mania to what could otherwise have been a straightforward documentary about the history of a famous stunt (which itself was an act of beautiful lunacy). And Petit’s manner, when he first appears in the film, signals to the audience that this is no ordinary documentary, however nuanced, about a group of people working hard and together, despite adversities along the way, to pull off something difficult. He seems to come from another universe, where mimes and jugglers rule. He is something unexpected.

Except of course that’s only because most of us, the film’s audience, were unfamiliar with Petit prior to his appearance in Man on Wire. To US audiences, when Petit declared he would be happy to die walking on a wire, he appeared in the context of a film about the World Trade Center, released only seven years after the towers fell, when our grief and memories of the morning of 9/11 were still fresh. If only we’d been able to read On the High Wire beforehand.

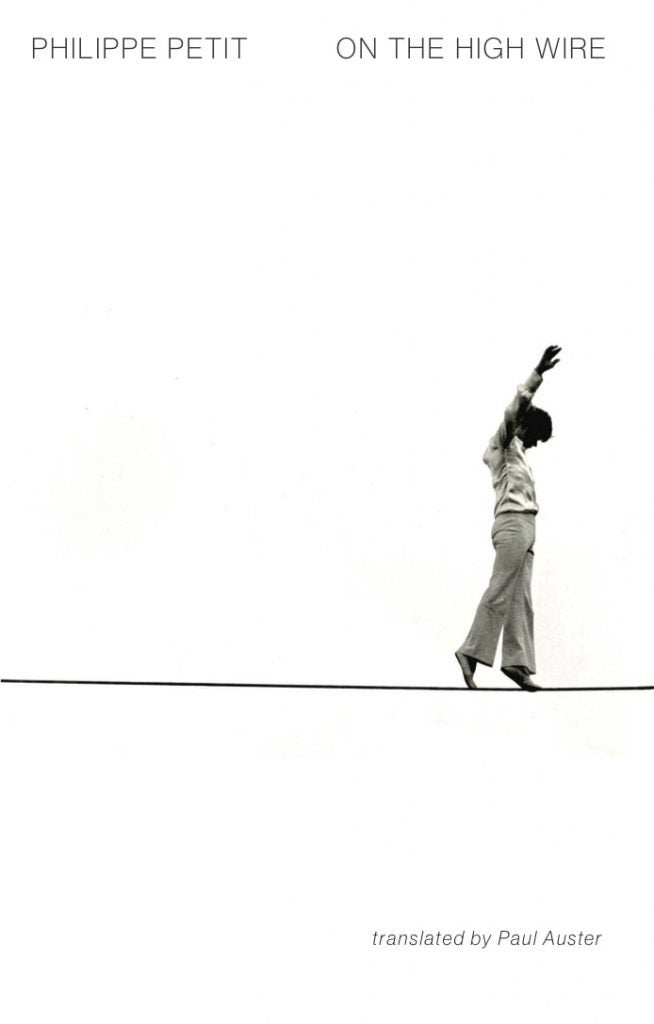

On the High Wire was written in 1972, when Petit was all of 23, and Paul Auster’s new translation of the book has just been published by New Directions. On the High Wire (2019) is a little (ahem, petit) thing, all of 115 pages including notes, with a trim size—4.5” x 7.3”—to match. In the hand it feels like a guidebook and reads like a dream diary. The book is both of those things.

Here’s a representative sample; for much of its length, On the High Wire is a curious mix of straightforward technical advice with little curlicues of personality sprinkled in:

When setting up for the first time, use a simple wire ten meters long, stretched out two and a half meters off the ground between two small poles—two X’s of wood or metal—or, even more simply, between two trees. Preferably, trees with character. Attach one end with wire clamps; on the other end attach a tightening device (a large turnbuckle or a level hoist) to a sling. At the tip of the cable make a spliced eye with a thimble inside it. Draw the eye toward the hoist hook with the help of a pulley block. Fasten to the hoist and tighten. Be careful to wrap the tree trunks with large jute cloths so they are not hurt by the wire.

“Preferably, trees with character.”

On the High Wire comprises twenty-five chapters, with titles like “Setting up the wire,” “The quest for immobility,” “The wire walker at rest,” and “Fear.” Though prose, many of the book’s sections are written in a sort of loose meter with deliberate line breaks. For example, the opening “stanza” (paragraph?) of the book reads:

No, the high wire is not what you think it is.

It is not a realm of lightness, space, and smiles.

It is a job.

Grim, tough, deceptive.

This opening sets the stage for the rest of the book: it is all at once extremely direct, rather poetic despite being so direct, and all the odder for it. In other words, it feels very much like the product of a dreamy young man who would one day perform death-defying stunts that stupefied in their beauty and risk. Though it may read and feel like a guidebook, On the High Wire is a diary in which “he” and the third person stand in for the use of “I.”

As such, it’s impossible to read the book without considering the subsequent history of the writer; On the High Wire would have given John Crowe Ransom and the rest of the New Critics fits, because to succeed—even, frankly, to be interesting—the book must considered alongside who its author is and what he went on to do after writing these lines in Vary, France in the winter of 1972. Amen that most of us aren’t New Critics.

The single chapter that best sums up the feel—its je ne sais quoi, if you will—of On the High Wire is one from the book’s middle, “Alone on his wire.” A mere two pages, the chapter is an entirely lyric rumination on the fear and joy of wire-walking, without the merest nod to the book’s technical information. Here’s how the chapter ends:

Alone on this wire, he wraps himself more deeply in a wild and scathing happiness, crossing helter-skelter into the dampness of the evening. He attaches his balancing pole to the platform before settling down at the top of the mast. There, in a corner of dark and chilly space, he waits calmly for the night to come.

What a strange, delightful book.

…

Notes

The header image of Petit walking between the WTC towers is from Rogelio A. Galaviz C.’s flickr photostream. The image of the WTC in the 1970s is from MrTinDC’s flickr photostream. Book cover image via New Directions.

And for bonus footage of Petit at the Oscars, making a coin disappear onstage, see below.