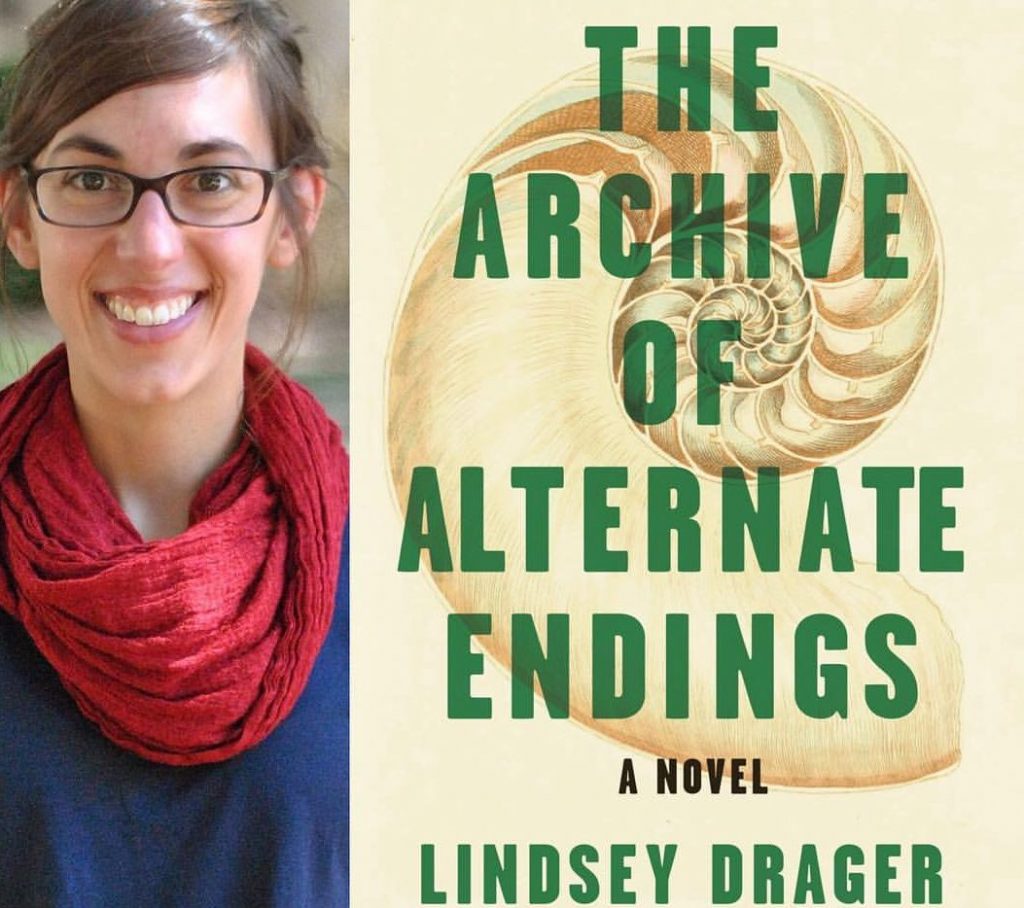

We human beings are nothing more than a collection of our stories, stories which comprise the vast histories of ourselves and the world around us, for better or worse. In Lindsey Drager’s The Archive of Alternate Endings (Dzanc Books), the author takes her readers on a ride through the vast and intricate world of human storytelling and the ramifications of memory and forgetting. Drager has a unique ability to breathe life into some of history’s most unique and unassuming characters, from world-famous scientists and Renaissance thinkers, to the fictional personalities of Hansel & Gretel.

Drager’s novel follows a series of characters, sometimes loosely related, through an interesting pattern. Over the course of one millennium—from 1378 to 2365 AD— The Archive of Alternate Endings is populated by numerous characters affected by the arrival of Halley’s Comet, which visits Earth every 75ish years after completing its long trip through our solar system, curving near the Sun and zooming past our skies. Each time it arrives, our cast of characters, including the comet’s scientist discoverer himself, Halley, ponder some current societal woe plaguing our tiny blue dot.

Alongside Halley, two of the novel’s main protagonists are Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, the famous writers who comprised Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the standard bearer for all things involving the folklore of ancient humanity. Early in the novel, Drager gives the reader a peek into the nature of storytelling and how it has been molded, shaped, and rendered unrecognizable in certain aspects over the years. While the Grimm brothers spent much of their early days recording the oral and written tales faithfully, over subsequent edits, they began to bend and shape the stories to make them more palatable, family-friendly, and lucrative. During one of their subsequent edits, a woman reiterates the story of Hansel & Gretel to the brothers Grimm and informs them that they have it all wrong: that the story is about a young girl who goes looking for her brother who has gone in search of other boys. “The story, she says, is about a sister who wants to save her brother. The woman says: the story is about a boy who loves boys and the parents who abandoned him because of it.”

Embedded within this narrative is the not-so-subtle insinuation that much of our recorded history—the basis for all our stories and histories—could perhaps be false, or at least incomplete. The ramifications of this revelation are grand, but Drager escorts her readers through the rest of the book, allowing them to understand just how deep this rabbit hole might go, all while focusing on one delightfully loose thread that weaves itself through a tapestry of meta revelations; at its core, this novel is meant to rattle foundations, and it does so in the best way possible. For Wilhelm Grimm, one early revelation he comes across concerns his brother and the nature of their work:

He would think: if he could tell his brother everything he has learned, it would read like a very sad primer. That soft arcs are deceptive, in stories or on paths. That nothing in this life is unbent, and as such all things intersect. That the sky is a projection of everything that lives within our frames. That there is no closer bond than that between siblings because they derive from the same cosmic formula and grow in the same flesh home.

These are the types of grand thoughts that Drager poses to her readers from page one, and the result is a truly cerebral experience. Not long after this, we are posed with another equally heady query: “Can a man live his whole life resisting his pleasure, or are we as a species condemned to bend toward our want?”

The realm of storytelling is a sacred one, and not just for authors and readers, but for our culture as a whole. As the novel makes readily apparent, if we neglect or ignore our collective pasts, our stories, then we risk losing the most important part of us forever. Drager also ruminates on the nature of our human relationship with stories on the whole:

For a story to enter the domain of a tale, it must have been through many mouths, passed through generations and across great distances. The story must move through many bodies and get shaped, become taut and succinct through those bodies, perfecting and honing its shape. Does the story reach this final state ever, or is its final state the malleable form in which it never calcifies?

The Archive of Alternate Endings gives life to queer narratives that have otherwise been erased from history. As it romps back and forth through time and space, the novel’s world is spread out and made even within the continuum. Drager masterfully aligns these competing narratives, guiding the reader through the novel with care. For a story that feels hopelessly predestined at times, there is an incredible amount of cerebral introspection, suspense, and philosophy here to delight even the most cynical reader. As The Archive of Alternate Endings implies. We are all connected through our stories, and folklore is the carefully curated history of the world laid bare.

The Archive of Alternate Endings by Lindsey Drager is published by Dzanc Books, and available at your local independent bookstore.