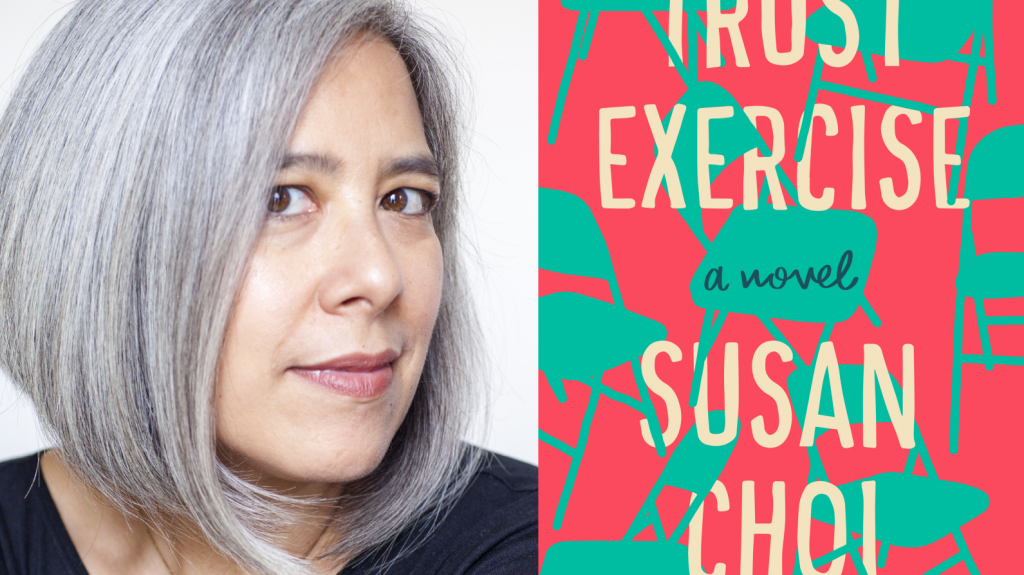

One of the most absolutely electric scenes in Susan Choi’s fifth novel Trust Exercise (Henry Holt and Co., 2019) takes place fairly early-on in the book. Sarah and David are sophomores at an elite performing arts high school. They’re fifteen, and the previous summer, they entered into an intense relationship. But after a series of misunderstandings, the two have had a falling out. Their charismatic teacher, Mr. Kingsley, a man who Choi describes entering a room “like a knife,” has learned about the relationship from Sarah, and he decides to take matters into his own hands. He sets up two chairs in the front of the classroom and has Sarah and David come up and face each other. For anyone with a theater background, this is a fairly standard warmup. A trust exercise.

But here, it’s a betrayal. With a perverse glee, Kingsley uses the exercise to force a confrontation between the two. He assaults David with the facts of his summertime affair in order to provoke a response and, by his explanation, access some genuine emotion. It is blisteringly unsettling, and in this way, completely gripping.

Power has always run through Choi’s novels, and more particularly the abuse of it. In this way, Trust Exercise feels like the tip of the wick. This is where the thread of it is the most visible, and this is where the flame is. Amid Choi’s lush rendering of adolescence is a visceral, disturbing portrayal of power, performance and vulnerability.

When I was reading Trust Exercise, I couldn’t help but think about Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry. The two novels share a lot, both thematically and structurally. Both books are separated into three sections of descending length. Both center on a mentor/mentee relationship and situate themselves within the uncomfortable power imbalances inherent to these relationships. And perhaps most significantly, both ruminate on the limits of narrative authority. But where Asymmetry‘s central question revolves around “whether a former choirgirl from Massachusetts might be capable of conjuring the consciousness of a Muslim man,” as Ayten Tartici points out in the Yale Review, Trust Exercise asks a question that is a little messier and, at least by this reviewer’s account, more rewarding:

How do we ascribe truth to competing narratives?

With a disclaimer for spoilers, allow me to explain: Like Asymmetry, Trust Exercise pulls a little bit of a Mulholland Drive. After the first section, which follows Sarah through her sophomore year, we shift into the perspective of Karen, one of Sarah’s classmates. “Karen” – whose name is not really Karen – informs us that for the first hundred or so pages, we’ve been reading a novel written by “Sarah” (whose name is not truly Sarah). Now an adult, not only is Karen utterly dissatisfied with her erasure from the story that plays out in Sarah’s semi-autobiographical novel, she’s also armed with her own version of the events of that year.

With the narrative now under Karen’s control, Sarah’s sugar-spun prose bottoms out, and is replaced with Karen’s sharp and striking voice. Her observations are dry and blatant, often brutal in their aptness; when Karen considers that she’s “not a special kind of victim,” I couldn’t help but think of Megan Fox saying that she was scared that she was not a sufficiently “sympathetic victim” for the #MeToo movement. But then, Karen’s version itself may not be all exactly right, either.

What ensues is a reckoning with not only the discrepancies between these narratives, but with the larger consequences of their omissions and revisions. A novel that feels so necessary for the current water we swim in, Trust Exercise is a stunning study of the increasingly muddied line between fact and fiction, the power of the stories we tell ourselves and the consequences of the inherent distortions of memory.

Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down with Susan Choi to talk about Trust Exercise, competing narratives and the nature of memory.

***

At this year’s AWP Conference in Portland, you were on a panel called “Timely vs. Timeless: How to Balance a Hot Topic vs. Creating Timeless Literature” with Tanya Selvaratnam, Sharma Shields and Julie Buntin. There, you brought up this concept of “competing storytelling.” In other words: who gets the authority over a story? At what point in writing this novel did the idea of using competing narratives emerge?

I didn’t even set out to write a book – let alone a book that would even work that way! I was working on a different book, and the work that became Trust Exercise started as some writing that I would do when my other project was going poorly. I thought this was going to be a short story. Some writers finish a big project and then get into writing short stories in between projects, and I always wished I could do that. So that’s how this started – as just some writing!

Because I didn’t have any plans for it, there was no pressure on it. I kept picking it up when I felt like it and kept putting it down when I felt like it. And then one day, I picked it up and it had changed. Without my thinking about it or worrying about it. Within an interval that I hadn’t actually given it any active thought, somehow the idea formed without my being aware. Someone was angry about the way this story was being told and they wanted to tell it differently. So I just went with that.

Both in Trust Exercise and in your other work, there’s a lot of talk about power and there’s a recurring setting of schools: more colleges and graduate programs than the high school setting here. What is it about the nature of a performing arts high school that felt like it should be the narrative space for this story?

When my third book came out, a really good friend of mine that I went to college and graduate school with said, “Wow, you just can’t leave academia alone, can you?” I was so chagrined! I never noticed! But I’m the daughter of a professor, I spent a lot of time going to school. I have been in the academic realm for so much of my life – it’s a world I know, I’m so interested in investigating it. It’s not that it’s rife with so many more problems than the rest of the world, but it does have its own interesting problems. But with this book, the characters came first, and the thorny dynamics of all the relationships emerged pretty organically.

In my experience of theatre in high school and college, it was a profoundly interesting world. It’s highly professional and at the same time it looks to mine the world of human emotion. It leads to all these strange tensions; these structured, ritualized ways to access unstructured spontaneity. The acting class itself is such a strange thing. It’s a system or a method to get beyond system and break free of method to find something authentic. But you’re doing it in a highly controlled way.

I was so attuned to the fact that the first section gives credence to the heightened level of how adolescents respond to things and process things. I feel like we often don’t give that perspective the dignity it deserves, we always consider it too blown out of proportion or inauthentic. Were there challenges or advantages to using an adolescent perspective while also interrogating the limitations of that perspective later on?

While I was writing, I never thought, “oh, is this authentic?” The worry of having not fully adult protagonists or if the perspective is going to seem too mature or not mature enough never bothered me because I was writing it for fun. A lot of it emerged before I got really self-conscious about questions like that, which is kind of great.

But after I did become more conscious of the larger shape it was taking and that it was possibly more my primary writing project, I did start thinking a lot about memory and the reliability of memory when you are talking about formative and painful events that may have happened a decade or two deep. Are peoples’ accounts equally reliable? That ended up being an asset instead of a liability because it ended up being part of the story, this question of whose story it is to tell.

Once the reader’s assumptions about what sort of narrative it is are challenged, you can open up the questions of how reliable are our memories, can we believe ourselves when we refer back to the things that happened to us, can we believe other people? I’m sure everybody has these people in their lives – I have a close friend whose memory is so much better than mine. I constantly ask her, “is that the way it happened? Is that the way things were?” because I don’t trust my memory as much as I trust hers. So what may have been a weakness for this story turned out to be what this story was about.

I feel like unreliable memories – and unreliable narration, for that matter – feels all-too-appropriate lately.

While I was writing this book, I thought about political storytelling a lot. I was fascinated by the war of political stories – what is this nation’s story? – and certain versions of that can be so compelling when they seem so manipulative and fraudulent. Somehow, these ideas are commanding attention and even belief, and they’re making people feel the way they want to feel. Maybe that’s what matters in our political life. How things that could shock and horrify one day can be easily digested the next. That version of our collective storytelling was astounding to me!

In Trust Exercise, a certain character encounters a person she feels has deformed her life and everyone acts as if he’s fine. She talks about the idea there’s a strange satisfaction of participating in that normalization herself. That she found it comforting to participate instead of being the lone voice of dissent. It’s comforting to go along with it and say he’s fine.

If you were structuring a conversation around this book in terms of other pieces of media – not just books, it could be music, movies, anything – what is in that conversation?

Everything by Muriel Spark! When I first started writing the sentences that were on the opening page, I was in a Muriel Spark mood. I had been loving how dark and misanthropic but still compassionate her books are. I also loved how lean they are – just a notch above novella. She’s so unapologetically knife-like in her storytelling, she just slices right in! She doesn’t take time to explain things to you, refuses to hold the reader’s hand. She’s so economical. At her best, she just plunges right in and keeps that momentum. Importantly, she’s not interested in the light side of human behavior. I go in and out of periods when I don’t want to read anything else but her.

I also loved Jennifer Egan’s novel The Keep. It’s gorgeously written and has amazing momentum, but it’s fun and mischievous. It’s kind of wayward. It has that moment of surprise where the nature of the storytelling is revealed to be different than you thought. I loved that. I didn’t consciously remember it when I was writing Trust Exercise. But I think it’s misbehaving in the same way the The Keep misbehaves.

I’m always in awe of Alice Munro. I love the way she pushes the limits of what you don’t show or tell the reader while still doing something so powerful. More powerful because of what you left out. I don’t like dutiful writing – when the writer says I want to account for this, I don’t want to confuse anybody. I like books that take you to the limit of understanding what’s happening without egregiously confusing you, but without coddling you.