Early in Michael Earl Craig’s Woods and Clouds Interchangeable, forthcoming from Wave Books, there’s a poem that I would argue serves as key to reading the book—and Craig’s work overall.

Specifically, it is the first stanza of “The Rabbit,” the collection’s third poem:

I remember the spring when the rabbit with no ears showed up.

Little pink stubs.

Were they bleeding?

Had they been ripped or chewed off?

The rabbit hopped about and enjoyed eating grass no differently.

At first it was unsettling, then amusing, then normal.

Then company would come and say look at that rabbit!

And it would again seem odd, unsettling, but eventually normal.

This is quite an opening, especially following such a nondescript title. The juxtaposition of the first line’s length—including the detail that it was spring when “the rabbit with no ears showed up”—plus the second line laconically describing said lack of ears, is striking. Furthermore, how the speaker doesn’t describe violence but instead suggests it, doing so inquisitively and with what I read as a touch of innocence (“Had they been ripped or chewed off?”) before immediately returning to the happy hopping rabbit is…disconcerting. Off-balance moments like this abound in Woods and Clouds Interchangeable.

But it’s not only the earless rabbit enjoying its grass that helps explain this collection. Instead, it’s a phrase that appears toward the end of the stanza above: “unsettling, then amusing, then normal.” This progression—of bewilderment to humor to acceptance—is akin to the stages of grief, and serves both as a guide to understanding Craig’s work, and as a map of what you’ll experience while reading it. I muttered an amused “what the fuck!” to myself a lot while reading Woods and Clouds Interchangeable. Which I mean as praise.

As another example, here’s the short poem “Maryland” in full:

When I threw that Chapstick down

onto the comforter it

sent ripples through

Maryland.

The collection’s 67 poems—with titles like “Who Was King Friday,” “Don Cheadle Poem,” “The Branches of Clowns,” and “Heimlich’s Beagles”—offer a trove of often absurd imagery and situations. But to label this work “absurd,” either in the sense of it being silly, or along the lines of the theater of the absurd, does it a disservice. The absurdity in Woods and Clouds Interchangeable, such as the book’s absurdity is, does not exist to make some point about futility or the meaningless of existence. Instead, the absurdity is illustrative and reflective: life, after all, is frequently ridiculous. It is what it is, to use a phrase that’s essentially the verbal version of the classic ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ emoji.

Perhaps more accurately, the absurdity in Woods and Clouds Interchangeable is life-affirming. It is life-affirming insofar as even its oddest scenes smack of believability (such as the greased hog floating down a river covered in what a speaking baby calls “opportunistic leeches,” as in “Town”; one could imagine seeing that) but also reinforces lived experience. One might not enjoy “Colosseum” as fully, for example, if one isn’t familiar with cafes (where the speaker is sitting), muffins, despots, or sriracha. It is work that, while sometimes exaggerated, also feels intimate. Here is that poem’s second half:

There is the sadness of unwed despots,

the chromed anger of the espresso nozzle,

a man with what looks like potatoes in his pants—

one in the front and one in the back.

People are squirting sriracha onto everything.

People, squirting sriracha onto everything.

As an inveterate sriracha-squirter, I attest to the truth of the poem’s final lines.

If I haven’t made myself clear by now, Woods and Clouds Interchangeable is frequently laugh-out-loud funny, though its humor is black and strange. Think Tim and Eric’s CORBS (Cops on Recumbent Bikes) more than the broad goofiness of Airplane! But like the best comedy, there is an undercurrent of seriousness that runs throughout Woods and Clouds Interchangeable. In Craig’s hands, the different modes aren’t at odds, and in fact work together perfectly; in a mere 35 words, “Who Was Simone Weil” includes references to Weil being nicknamed “The Martian,” her having small hands, and includes the devastating final lines “Sometimes / writing less is / okay. Is best.”

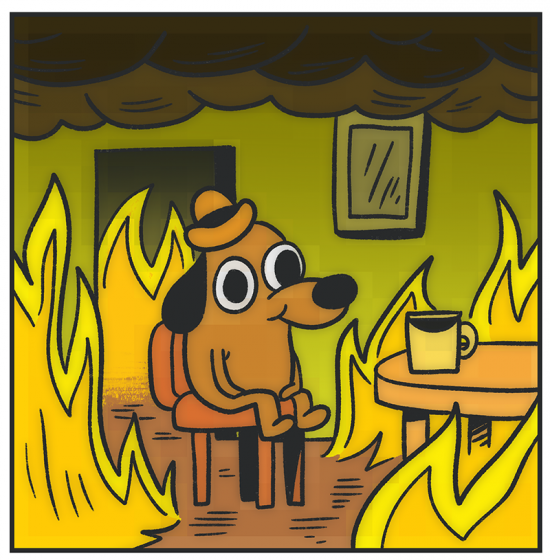

Put another way, the collection reminds me—again, this is praise—of the “This is fine” meme. The meme’s coffee-drinking dog, in a room on fire, insisting everything is fine, would fit right into the world of Woods and Clouds Interchangeable.

And then there is the book’s fascinating final poem, “Briskly Jerked Rugs,” which complicates a reading of Woods and Clouds Interchangeable. For one, “Briskly Jerked Rugs” is a truly long poem, at 20 pages and 340 lines, and as such contends with the usual issue of sagging—or not—under its own length. While some long poems (such as Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” which I reread recently) use a central argument or theme to give the poem a structure and to keep the reader engaged, “Briskly Jerked Rugs,” instead comprises a dizzying, frequently shifting, succession of images and sometimes scenes, which is itself a manner of structure, albeit one that is elusive and difficult to hold onto.

Here’s a representative sample:

The forest was full of chainsaws, and Dutch men in swim thongs.

The choir looked ashen; they sang in earnest of eternity.

At the edge of the snow I encountered a bag of tangerines.

To cuddle now seems disingenuous, observed Lorna, swatting at a fly

with a rubber ruler. Jessie shook his bangs like a pony, dumping Splenda

into his breve. He nodded, and murmured, and listened to Lorna.The forest smelled of gasoline. And mushrooms. And coconut oil.

The choir looked startled, belting out “Blessed Assurance” with bluster.

A limping child could be heard dragging her knuckles in the hallway.

A holiday wind ascended the glen, whatever that meant.

We’d turned over a new leaf as they say. Words of atonement

moving low and cold like propane through the orchard.

The number of things happening, things to visualize in these two stanzas, is overwhelming. What is the mind to do when it’s asked to switch from a forest of chainsaws, to imagining Dutch men in swim thongs, to an ashen choir? How does one deal?

Perhaps by following the “unsettling, then amusing, then normal” guide. The more one reads Craig, the more one accepts—and looks forward to—the sudden shifts. Indeed, the surprise and delight of these shifts, which I think of as a sort of swinging back and forth, and which arise fully formed, even in just a few words, are at the core of Craig’s genius.

…

“This is fine” image by artist K.C. Green, via Wikimedia Commons