“Chapman’s Heart,” by Michael Byers, appears in the Winter 2019 Issue of MQR.

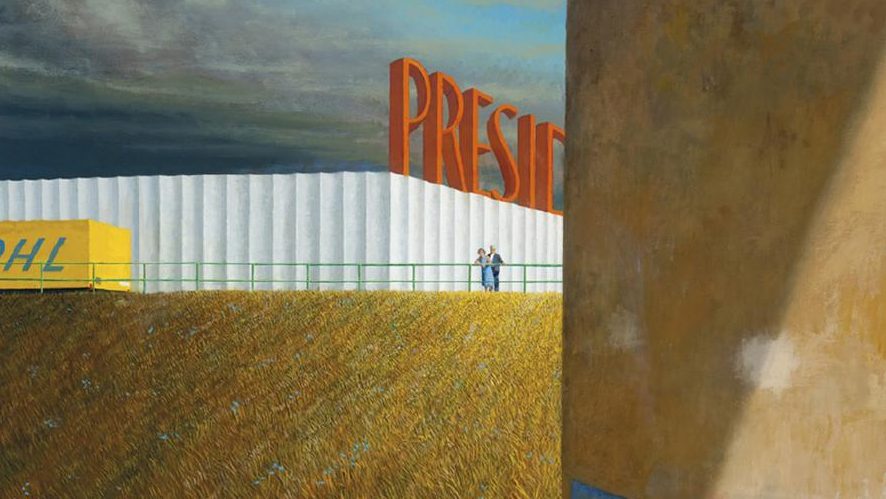

It was a new program, long-argued over, newly implemented. Before a president, any president, could launch the weapons that would kill a billion humans, he, or she, would have to murder Chapman and extract the mesh from his aorta. To kill billions impersonally, the president must first kill one man in person.

Liberal lunacy, the Republicans had cried. A security vulnerability of the highest order.

A moral proposal, the Democrats insisted.

No taxpayer money will pay for this, the Republicans declared.

A private fund was assembled to pay for the surgeons, the hospital, the recovery drugs.

He cannot sleep in a government facility, the Republicans decided. Ah, but the East Wing of the White House is a private residence, the Democrats pointed out, and a Special Executive Finding was produced that showed exactly this, enough to pass muster with the Supreme Court, anyway, and therefore Chapman’s bedroom was fifty feet from the President and First Lady’s. He was in the Queen’s Room, with its own bathroom and sitting room, which offered a view of the north lawn and Lafayette Square and beyond that the low, humble skyline extending north toward Silver Spring.

There was a salary. Meals were provided from the private fund. He would always be within sixty seconds’ reach of the president—this president, and maybe future presidents too, as long as they were Democrats. The mesh would not degrade, the launch codes would never change.

The president was briefed, Chapman gathered, on exactly how to insert the knife, exactly where the mesh was secured. The president had practiced on a dummy. Possibly a cadaver. The DSO was not forthcoming on this detail.

“He’ll know just what to do,” the DSO assured him.“It’ll be quick, if it happens.”

“Otherwise, I’m just around.”

“Just around,” she said,“and also representing all mankind.”

The president insisted he call him by his first name: Leonard.“It just seems fair,” President Holt said, at their first meeting, just before inauguration day.

“I think I’d prefer to call you Mr. President, Mr. President.”

“Let’s make it an order, then. Just don’t call me Lenny and we’ll get along fine. You’re living in my house, after all, I guess you can use my real name.”

“Yes, sir. Lenny. I mean, Leonard. Sorry, sir. I’d be honored to call you Leonard. Thank you.”

“Did you vote for me? I think you must have or they wouldn’t have picked you.”

“Yes, I did.”

“Why?”

“You’re a Democrat.”

“Did you vote for me in the primaries? Where are you from again?”

“Virginia. Arlington. Yes, I voted for you in the primaries.”

“Why?”

“How much detail would you like, sir?”

“Just the executive summary.”

“I agreed with you on global warming, and withdrawal from the Middle East, and mass transit and high-speed rail, and I thought you could win, because you’re tall and handsome and funny and you don’t seem like a robot.”

President Holt regarded him from under his dark eyebrows. He was handsome, he was funny, he was more or less exactly what you wanted in a president, and he had won by an almost embarrassingly wide margin. “What did you do before this? I guess there’s a file on you somewhere, but honestly I haven’t looked at it.”

“That’s all right, sir.” Of course it was all right.“I mean, of course it’s all right.”

“You were some sort of government employee.”

“Yes, sir. In the Department of Agriculture.”

“I see. Doing what?”

“My field is soil science. I have a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. My particular field is erosion reduction. Farming without plowing is my specialty.”

“We can do that?”

“We did it for eight thousand years before we invented the mechanical harrower, and then we started plowing at depth and then we got the Dust Bowl. And we’ve been losing topsoil ever since. The pioneers were working with topsoil that was eight and ten feet deep. Now it’s down to inches in most places. We don’t have any left to lose.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes sir.”

“Where does it all go?”

“Well, it just blows away. Eastward from the plains. It mostly lands in the Appalachians, actually. Eventually it washes down the Mississippi and into the Gulf of Mexico and then, pfft, gone.”

“And why did you want to do this, Chapman?”

“Because I believe it’s the right thing to do. To make you kill a man before you kill the human race.”

“I’m not going to kill the human race.”

“No, sir, I know. But I agreed with the thinking behind the policy.”

“A symbolic protest against blind, murderous indifference,” the president suggested.

“Something like that.”

“So now there’s a knife you carry around that I’m supposed to use to kill you, if it comes to it.”

It seemed the thing to do to lift the case and offer it across the desk. President Holt examined it, pressed a series of numbers into the keypad, and the case snapped open. The president turned the case around. “There it is.” A slim steel blade, a thick black handle.

Perfectly unremarkable, in fact.

“Thank you for showing me. I was wondering what it looked like.” “It looks like a knife.”

“Have you ever killed anyone, sir?”

“Well, not that I know of,” said the president.“Not yet.”

When the president was in Washington, which turned out to be most of the time, the very large majority of business was conducted in the White House, which meant Chapman spent most of his time there as well. He settled in. The Queen’s Room was spacious and comfortable, with a four-poster canopy bed. The adjacent sitting room, also Chapman’s, had bright blue floral wallpaper chosen by Jackie Kennedy. He grew to admire the changing view, the shifting colors of the leaves. The window glass was bulletproof, which meant a great silence prevailed. The silver darts of planes from Reagan National split the air without a sound. He was not allowed in the West Wing without permission, but he could roam freely through the kitchen and the staff areas and the basement, though only in the company of the rotating security detail that followed him everywhere, two big agents in dark suits, all interchangeable, all sleek and lethal under the direction of Antonio Paz. Chapman was a shadow, and the agents were the shadows of the shadow.

First Lady Marilyn Holt was a warm, short, fluffy-haired Italian from New Jersey, bright-cheeked and loud and unshy. She had been the other reason he had voted for Holt. “You slightly creep me out, Chapman!” she exclaimed one evening, encountering him in the ground-floor library, where he had taken to spending a good deal of time.

“Yes, ma’am, I’m sorry.”

She fed him a manic grin, full of teeth. “The constant specter of death, ever warning us back from the precipice!”

That was the idea, anyway, he admitted.

She performed a little shiver in her blue satin gown. “You were a professor?”

“No ma’am, I was in the Ag Department.”

“That’s right. No kids. But an ex-wife, right?”

“Right.”

“What’s she think of this?”

He had no idea. They had not been in touch in ages.

“I don’t want my husband to have to murder you.” She extended a stubby, warning finger. “Just so you know. I think him having to kill you would be bad for our marriage.”

“Thank you, ma’am. Not to mention the planet.”

“Not to mention!” she cried.“Like an organ donor! You’ve donated your heart to the cause of peace on Earth!”

“I wasn’t using it for much,” he said.

“Ha! Well, good for you, making yourself useful after all.” And she turned and sent up a great weary laughing sigh as she went away toward the stairs. She had been a prosecutor in her old life, putting away white-collar bad guys, and was beloved by anyone with a functioning brain, at least in Chapman’s opinion.

“You’re wonderful, ma’am!” Chapman called after her, surprising himself.

At which she turned, shot him a saucy look, and laughed again…

Purchase MQR 57:5 or consider a one-year subscription to read more. This story appears in the Winter 2019 Issue of MQR.