“First I want to say this feels incredible. To be female, to run and run and run to not see any end in sight but maybe have a feeling that there’s really no outside to this endeavor this beautiful thing. You know we don’t have a single female on any of our bills. And what about two women, two women loving. Or even more. A lot of women.”

Kennedy Coyne: Thank you for meeting with me. I’m writing my thesis, and I was looking at Chelsea Girls, but I was also looking at more contemporary narratives like The Argonauts and Chloe Caldwell’s Women. I was wondering how narratives have changed, and how are things different? What was interesting about Chelsea Girls was that you’re speaking to this past historical moment, and I was looking at it in terms of the waves of feminism.

Eileen Myles: Which?

KC: You write about your fictional experiences that occur in second wave feminism.

EM: I don’t agree with that reduction. I would say the narrator, the Eileen character and Chris do not feel comfortable or part of it. It’s sort of like me. I don’t really identify with second wave feminism and I didn’t then either. We were predicting third wave.

KC: I don’t think you were intentionally doing it. I see second wave feminism as a collective talking about experiences that created assumptions. It sort of groups people together. What I saw Chelsea Girls doing was speaking not exactly from third wave. The character resists collectivity. You’re writing in the 1990s—

EM: I wasn’t writing in the ’90s, I was writing in the ’80s. The book was published in 1994 and a couple things might have been written in the ’90s, but the bulk of it was written in 1980s. The first story was written in 1985. “Bath, Maine.” I’d say it was written from 1980 to 1993. The story “Chelsea Girls” I did in 1990. “My Father’s Alcoholism” was written in 1990. “Bread and Water” was actually written in 1970, probably ’79. It was written literally in the moment.

KC: Why did you choose to publish them in ’94?

EM: That’s when I could. When I was writing them I felt two things. One, the thing literally about me, the narrator, wanting to make a film was true. There is such footage that we made. First the stories, the chapters, arised out of an impulse to make film, and to document a certain kind of female life and a certain kind of poet life. It’s invisibility both in feminism and in the larger culture. I was writing a novel without higher confidence that it would happen. I just kept accumulating every time I would think of a scene. I would go to that place and I would download it, and just see what there is. I wrote “Bath, Maine,” sitting in a kind of a lunch place in Tulum. Like, there was a place in the ’80s in Mexico that had grass huts on the beach for like a dollar a night where you could get conch tacos. It was Mexico hippies and myself, who was newly not drinking. And when I was sitting there, I was wondering whether fiction could be like writing postcards to yourself from one part of your life to another. Like acting as if the self was the receiver of a postcard or a letter. So what you’re saying in the first place between these generations, but it’s interesting that they’re all located in a way within the self, the kind of security of the self. But it was always a kind of fraught issue whether these stories or chapters would come together to create a book. So I think the first time they were published.

I think someplace in the early ’90s I thought, “Well, okay, I think this can be a novel.” And I sent packets of it to agents and editors. They said these stories weren’t publishable, they didn’t have arcs, they didn’t come to anything. They weren’t redemptive. And it’s like, why would they be redemptive? You know, it’s crazy. So I think finally a poet named Tom Clark hooked me up with Black [Sparrow]. So even though my first impulse was mainstream, I went to Black Sparrow and then John Martin said, “These are stories, right?” and I said sure. It was a novel but I had no interest in fighting, I just wanted to get it published. And that was ’93.

KC: I was also looking at Not Me, because that was published in ’92 or ’91.

EM: Around there. And those are ‘80s poems.

KC: So they were probably written around the same time [as Chelsea Girls].

EM: A lot of what Not Me and its not overt theme is, I think, suddenly living in the world without alcohol and drugs. I hate to make that be what the poems are about, because they’re not. It’s just like it’s this incredibly different vista of New York City and also just the city at that moment, too. Not Me meant like this path that was not about me. It’s like being a hoarder and needing to make a path through. But the world was sort of like a pile. I felt like I was not me, just something that I moved through. Moving is narration, I think.

KC: And your poems read like stories. When I first read Chelsea Girls I was sort of like, “How am I supposed to read this?” The sentences were fragmented or run-ons.

EM: The first thing I wrote in the book was “Bread and Water.” And the rules were just to write exactly what I heard, exactly what I saw, exactly what we were doing. The fragments were the way the camera was operating.

KC: It reads like a conversation, like you’re talking through the whole book. In Chelsea Girls you’re conscious of your audience but it’s more like you’re talking to yourself. So it feels like a dialogue with yourself, aware that other people are there.

EM: Right. In a way it’s sort of like leaving something to be left. It’s like a live relic. Certainly, Chloe [Caldwell] and Maggie [Nelson] are two writers whose work I love. I’m sure I’m influenced by them by now, because it starts to bounce back. But it’s very generative across the board.

KC: I was talking to Rebecca [Wolff], and my advisor, Eric Keenaghan, and one of the things they said is that it’s hard for a poet to break into fiction or narrative. And it’s hard for those writing narrative to write poetry. How do you make that connection in your work?

EM: I feel like I don’t do anything different, really, except that I take more space. I anticipate more spaciality in the work. I make as much as I listen. I feel like poetry you’re really listening. With prose you start to become something that you’re in. It’s spatial, I think. You anticipate somebody reading it that way, too. But it’s just like, rhythmically, it’s taking longer. It’s the difference between running across the street to catch a light and running for forty minutes and doing three miles.

KC: I’m assuming that you’re conscious of your word choice. Or do you just go for it?

EM: Well, what’s the difference? You go for it with the mind that you have in the ways that you experience language. I feel like, language is simply exciting. What I love about New York is that you hear little snippets of conversation all day long and you’re so intensely meeting people. You can pull back, but then you start to wonder why you’re here. I grew up in a family of readers. The library was the shrine. I feel like language in this place is kind of what you’re in. When Frank O’Hara has that line, “You go on your nerve,” but your nerve is well-equipped. You carry this whole library on your back. I feel like I have conversations lately where people acknowledge that poetry doesn’t stop when you stop writing a poem. How is this not poetry? The poetry of the room is real literature.

KC: My understanding of poetry is that your reader should be intimate, and I’m not sure that everyone accomplishes that, but you do it with you poetry and your prose. It’s like you’re creating this world, but your reader is still a part of it.

EM: I think that’s part of, not so much the test of reading it, but that you might not be comfortable with that. You know what I mean? I think people who don’t like my work, they can’t abandon their own rules and just go with it. They may not be willing to do that. Every now and then I get an editor that wants to move this here or there. There’s this assumption that something is broken. That’s not to say that my work can’t be criticized or changed, but it’s just an assumption that there’s a better order or a more normalized, more readable experience. That’s not what I’m interested in giving anyone. But the intimacy is truly something I want.

KC: Thinking of “An American Poem”and thinking of your inauguration speech, do you think of politics as you’re writing? Are you consciously political?

EM: Sometimes when you’re sort of perusing material or you’re thinking about something, and I’m thinking about something that’s going through my mind and suddenly I get this excited feeling that this is so of this moment. You know what I mean? When I was writing “American Poem,” it started with me being on a train with somebody and sort of bullshitting them about my background. When I was young we would hitchhike, when I was in high school, we would be bad and we would put on fake French accents and tell them we were other people and it was part of this like little girl thing. So I was kind of lying to somebody and suddenly I realized she was believing me, and I thought, “Oh that’s so amazing.” It was so close to then that I decided I was a Kennedy. Even then the feeling and writing was that I could now accommodate a political statement in a poem seamlessly. I didn’t have to go there. I was entitled. It was such a political perception to realize that I was entitled to this content because there I was and I had not been entitled before because of who I was. So it’s just the process of the political, and the residue, the thing I was left with after it was political.

KC: Because that’s probably one of your most popular poems.

EM: It’s like that and “Peanut Butter” are the big hits.

KC: Who now influences your work? Does anybody consciously influence your work or are you just taking it all in?

EM: I mean, whatever I’m reading. I was just reading somebody while I was writing my next book. I read Bruno Schulz. He’s a Polish fiction writer who was writing during WWII. He was a Jew and he was a high school art teacher and a fiction writer, but at that point in Germany there was a whole kind of world of experimentation and fiction in newspapers, which was crazy. And he was known, but it was like occupied Poland, and there was one Nazi general who loved his drawings and there was another Nazi general that hated that guy. So one day Bruno Schulz was out eating a loaf of bread and the guy that didn’t like the other guy just shot him. But I’ve read his fiction recently through a panel I was on where there was a Polish critic and she mentioned Bruno Schulz and something about the ventriloquist dummies. And he’s fantastic. He’s related to Kafka in a way, but he’s very visual. He was really important to me.

And I only just recently started to read Thomas Bernhard. Everybody’s read Thomas Bernhard, you know? He’s an Austrian fiction writer. He’s sort of the shit—for fiction writers of my generation. And everybody (like Lynne Tillman) has read Thomas Bernhard.

The huge writer who’s really important to me right now is a Taiwanese novelist that died in 1996 and killed herself at the age of 26. She wrote two novels. Her name is Qiu Miaojin. She’s amazing. She’s important. I’m a huge reader and I’m always excited and moved by the thing I’m reading, including my friends like Maggie [Nelson] and Chloe [Caldwell]. Michelle Tea is a great example. She’s somebody who’s influenced by me, but I almost know better than anybody else how different she is. I’ll see her do something I wouldn’t do, then I’ll see her do something I can’t do, I won’t do, I didn’t do. It’s so interesting to see your work spread and grow and be someone else’s work entirely. Of course, James Schuyler, Frank O’Hara, Gertrude Stein, Henry Miller, Christopher Isherwood, are all people who have given me my work.

KC: So, what is your Instagram aesthetic? You post a lot, but it’s your eye.

EM: Of course. What else would it be? It feels apparitional, like poetry in a way. I may be thinking a lot of things, or thinking about things, or heard about things, but then I’ll get a line, and then I’ll write a line. Sometimes it becomes a poem and sometimes it doesn’t. Moving in the world I’ll see a wet paper plate next to a post and it’s minimal, it’s conceptual. Visual accidents. The world is filled with them—a bathroom, or just a funky bit of grafitti that’s really great in the bathroom, or the way the toilet roll was installed. Or sometimes I pick up my phone and it’s already on camera and it crops in a way that is accidental and great. I think a few years ago when we started to become conscious of browsers and they started having browsers and Google was the great revelation because it was a browser that catered to left-brain associations that helped you find things. I think since the ‘90s we have increasingly been about lists—what you’re listening to, the places you go to. We’re so atomized information-wise, and you can really just stay with the people who drink Americanos black. It’s so easy to keep everything away except for the specific thing I’m interested in. I think the thing that’s exciting then, is if I’m interested in sci-fi and I’m 60-something years old and I’m wearing plaid today, who else is on that list?

There’s a photographer, Wolfgang Tillmans, and I feel like a lot of what his work (kids, rain, street, graffiti, posters), shows you how he moves through the world. The implication: boom, boom, boom, boom. This is my narrative. This is the poet’s body, moving through space. And so that’s what Instagram utterly is for me, a moving portrait gallery of reality and how beautiful it is. I get high from the radiance of being alive.

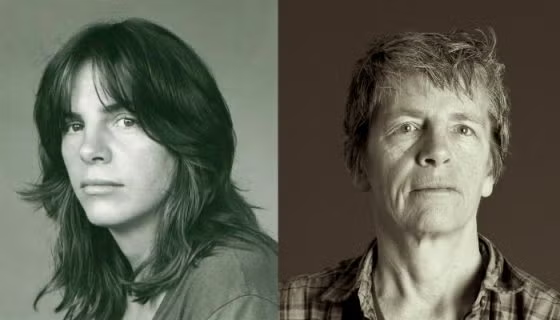

Photo Credits: Robert Mapplethorpe, Catherine Opie.