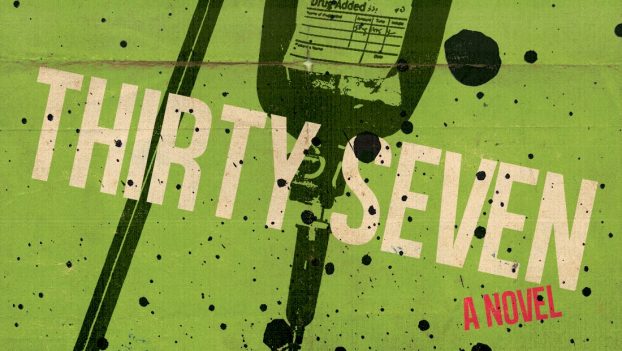

Change is something that many of us strive for—changing ourselves, changing others, and, most particularly, changing the world. But too often we expect radical change without having to put in the work to achieve it; we ignore the arduous tasks that precede major transformation and just continue yearning, searching. Enter Mason Hues, the protagonist of Peter Stenson’s engrossing and brutal second novel, Thirty-Seven (Dzanc Books).

Mason is something of an enigma—part survivor, part idealistic youth, and part ruthless cult member. The epitome of the unreliable narrator, Mason goes by many different names throughout the novel, including Jon Doe, Thirty-Seven, and eventually, One. Leaving home in his mid-teens due to an abusive stepfather and an unrelenting sense of longing, Mason arrives at the secluded Colorado home of Dr. James Shepard, also known as One. Before long, Mason has joined One’s cult that promises to bring its members closer to “Truth” in a world they believe is riddled with lies and despair. They achieve this by willingly taking Cytoxin—a drug normally administered during chemotherapy—to induce crippling sickness that will bring them to the brink of death in an effort to become closer to the Truth. After things go haywire and Mason is left as the only survivor of the mass suicide-murder known as the “Day of Gifts,” he decides to live out his life in relative anonymity following stints in juvie and psych wards. Then he meets Talley, a young idealist who reminds Mason of his former self, and the cycle seems destined to replay itself once again—only this time, Thirty-Seven becomes One.

Thirty-Seven is not a book for the faint of heart, but in a modern America where our society seems desperately split in half—relegated to our respective cult-like groups sharing our beliefs—it seems all the more pertinent. At its core, this novel is a cautionary tale for those who go out seeking, those among us who take that one additional step over the line, who peek their heads behind the curtain and disappear through the velvet. And while Mason may have begun his journey as an idealist searching for a better world of Truth and Honesty, as a narrator he presents readers with a much darker view, including this grim description of the state of the “American Dream”:

Every conversation is one-sided, a mirror reflecting looks and status and wealth. Every person is steeped in want…filling themselves with goods and sex and alcohol and validation so they forget about the fact that they all will die.

Despite such forbidding proclamations, Mason is an incredibly nuanced and sensitive character. Stenson has accomplished the incredible task of presenting his readers with a protagonist that shocks and horrifies us, as well as breaks our hearts with his honest sense of yearning and, sadly, misguided betterment. Mason participates in gruesome acts of violence, some more damning than others, and yet, Stenson has so well-crafted his protagonist that readers cannot help but to somehow sympathize with this young man, if only because we know Mason is much like an onion, with many layers lying underneath; and just when you think you’ve pegged who Thirty-Seven truly is, another layer falls away.

Some of the revelations within Thirty-Seven come by way of a personal aside in the form of footnotes. With this technique, Stenson cunningly gives readers a sense that they are being given a direct truth—some nugget of evidence that speaks to Mason’s inner self—but the real truth of the matter is that Mason not only seems to be hiding elements of himself from everyone within the novel—including Talley, his therapist, and even his original cult leader, One—but also from the reader; the asides serve only to further cloud the matter and deepen the mystery behind, well… everything. And though this might sound convoluted, it is anything but. The more closely we read through Mason’s past history and his emotional states, the harder it is to set the book down.

As with all novels told through an unreliable narrator with a psychological bend, it is imperative for a reader to never let one’s guard down when assessing both the protagonist’s actions and thoughts. This is immensely rewarding within Thirty-Seven because of just how sensitive and thoughtful Stenson has crafted Mason. Fiercely intelligent and uncompromising, Mason feels as if he understands the inner machinations of all the individuals around him, and more often than not, he’s correct, which further places him within the good graces of the reader. He is able to endear himself to us through his confessional tone pocked here and there with mindful bits of food for thought, including:

We outgrow experiences even before they are over.

We are granted the curse of consciousness, once an asset in assessing danger, but now without actual threats, it has become a virus multiplying self-centered thoughts about things that shouldn’t matter. Everything becomes hypothetical. Everything is Prince Charming slipping on glass slippers to our different futures.

Though this is far from unfamiliar for someone like Mason, who himself is keenly aware of the power of cults to enrapture minds with a “broad and loose narrative,” as he discusses with his therapist during recovery. And yet, despite understanding the basic underpinnings of a cult-like mentality, Mason employs them in his own right, uttering phrases such as “We don’t fear the cliff—we fear jumping.” Despite this, though, Mason is clearly a passionate overthinker, a young man stuck within the cycle of questioning everything to the point of oblivion; if everything means everything, then nothing means nothing. The reader, along with Mason, soon becomes trapped within a wildly engaging series of philosophical queries about the nature of self, Truth, and reality.

For fans of the more anarchistic works of Chuck Palahniuk, as well as those who value the brutal honesty and grittiness of Hubert Selby Jr., there is no greater talent than Stenson. As a writer, his maturity and intellect dwarf Palahniuk and his lyrical beauty in the face of unspeakable violence and emotional torment hearken back to the most impressive novels of Selby, including Last Exit to Brooklyn and The Room. Thirty-Seven is a novel of immense psychological scope that showcases the talents of a fearless writer in Stenson whom has written a story perfectly-crafted for our modern tribal leanings.