During my freshman year of college, a classmate suggested in the margin of a story that I submitted for workshop that I read some Bukowski, saying that it had influenced him and believing that I could benefit from it. I’d admired the work that classmate had submitted to our workshop for its wry sparseness, and so that afternoon, I went to the nearby bookstore and bought the first Charles Bukowski book I saw. I was prepared to be changed. To magically actualize as a writer. To feel — as the books I’ve loved have always made me feel, in one way or another — seen. But in a book called Women, I couldn’t find myself anywhere. In a novel where women were little more than a few disparaging descriptors and a series of phases in the protagonist’s life, it wasn’t merely that I couldn’t connect: I didn’t feel welcome.

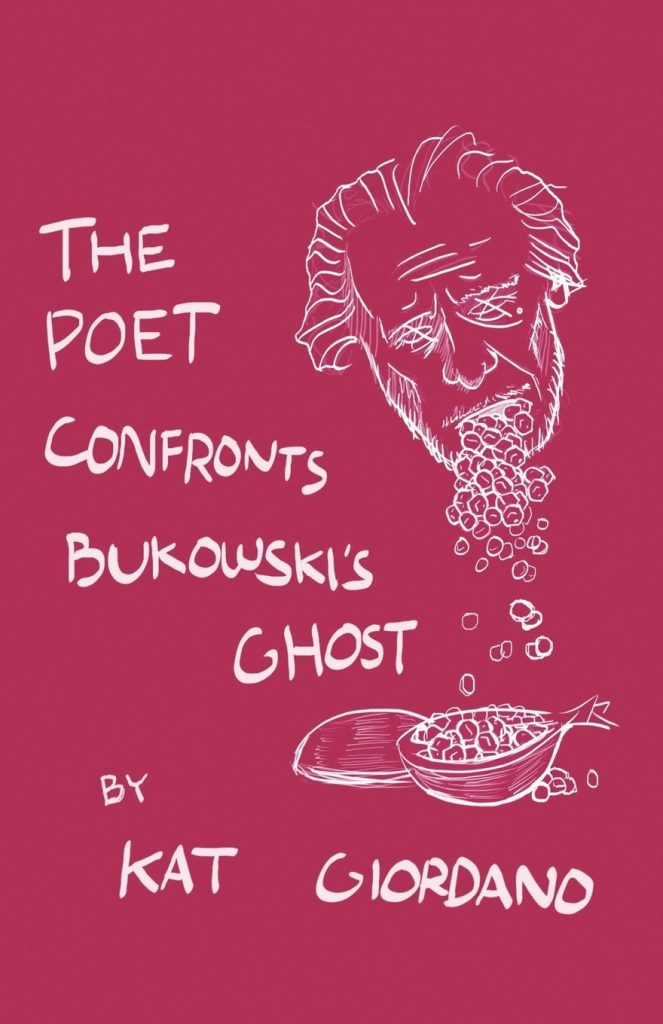

I’m not sure what to call this feeling, the kind of heat between my ears that was neither fully frustration or outrage or shame. But it’s the same righteous nausea that sits beneath the poems in Kat Giordano’s The Poet Confronts Bukowski’s Ghost (Philosophical Idiot, 2018). In this debut, Giordano faces the specter of a certain famous drunk poet and the culture he represents with equal parts grit and generosity, with both genuine discomfort and tempered rage. “It’s true what Bukowski said about style,” the first poem in the collection begins. In the titular poem, Giordano deals with the infantilizing discomfort of wanting to emulate the very writer that degrades “girls like [her]” before literally fighting his ghost.

Which is to say that this collection is also often deeply funny at its most pained, the poetic equivalent of well-executed slapstick. “The piano falls on your head and you become some crinkled accordion, swaying for a few seconds but always popping back into shape,” Giordano notes in “Once You Go In You Always Come Out Alive.” It might as well be Giordano’s Ars Poetica (though the collection does feature two well-rendered Ars Poeticas). Or, at the very least her general artistic process — to offset the devastating with the cartoonish. “It’s hard to tell if I’m the aching or the ache,” writes Giordano in “Two Buckets” before considering, “I once found a chicken foot in a chicken finger / and tweeted a photo to the company. / Their response was a coupon for more chicken.”

All told, much of The Poet Confronts Bukowski’s Ghost is about that awkward space of finding value in things that ultimately don’t find value for you in return. For Giordano, hate is too simple an emotion and admiration is too fraught a process. Instead, there’s discomfort, and the humor inherent to the routine alienation you feel when confronting the things you hate to love. Be it home improvement shows or painfully relatable memes or even, yes, a very famous misogynist that might just be your favorite poet.

Recently, I had the chance to talk to Kat Giordano about her debut collection, the tragicomedy that is HGTV, and finding surprising inspiration from Jaden Smith’s tweets.

I would love start this interview with the title — and by extension, the titular poem. Which is to say I think a lot of this collection is exactly about confronting what Bukowski’s ghost would/does represent. One of the interesting threads through the collection involves shaking off that Bukowski-esque presence in poetry where women are invisible or just their, you know, soft bodies and unreasonable emotions! You do a lot of interesting work of leaning into and pushing against the way that whole era of poets and poems characterized women. Was this a mission from the outset or was this a theme you noticed popping up again and again in poems?

While it was not necessarily a mission, I definitely feel that my interest in this theme developed as a response to some of my own experiences over the one or two years in which this book was written. Most significantly, I think, around a year ago I had an awful run-in with a “mentor” who, in addition to being generally manipulative, embodied a lot of the Bukowski-esque ideas that I found myself constantly tackling in these poems. That experience, as well as a few others, really raised the stakes for me on pushing back against a set of ideas that I had already known to be toxic culturally and socially and now knew to be toxic to me personally.

While it was not necessarily a mission, I definitely feel that my interest in this theme developed as a response to some of my own experiences over the one or two years in which this book was written. Most significantly, I think, around a year ago I had an awful run-in with a “mentor” who, in addition to being generally manipulative, embodied a lot of the Bukowski-esque ideas that I found myself constantly tackling in these poems. That experience, as well as a few others, really raised the stakes for me on pushing back against a set of ideas that I had already known to be toxic culturally and socially and now knew to be toxic to me personally.

In light of the MeToo movement on the whole, as well as the stories of men the positions of power in the literary community, this collection is touching on something painfully relevant. But there’s so much power in here of reclaiming a lot of these notions of what it means to be emotional and live in one’s emotions, to exist and write in a body that is constantly being appraised by the world at large. In particular, I loved how much these poems reclaimed the domestic by discussing aspirations of homeownership. Especially, as a pretty shameless fan of the Property Brothers, your poems about HGTV! What about HGTV spoke to you?

For me, HGTV has come to represent a way of life or a standard of living that is, if not totally inaccessible, kind of unrealistic for my peers and I, to the extent that I find it darkly funny. I think that HGTV appealed to me as a topic because watching it, I feel like I’m being sold a version of prosperity/adulthood that feels increasingly alien to me the closer I get to an age where I feel expected to attain it. There’s just such a wide gap between what people on, for instance, House Hunters are doing and the choices they have the power to make and what my life and the lives of the people close to me look like. I can’t help but notice that discrepancy and feel alienated or frustrated, despite on some level enjoying those shows all the same.

On the subject of references to media, etc., this book interacts a lot with pop culture and literature. But which works of writing or art and/or artifacts of pop culture that do not appear in this collection were helpful or influential in its creation?

If we’re talking about pop culture, there’s actually a little-known origin for around a third of the poems in this book. I went through a phase where I wrote prose poems based off of Jaden Smith’s tweets as a fun writing exercise. My original intention was to put those into their own chapbook, but they fit so well and added some much-needed (I felt) levity to this collection, so I put them in. I feel like this was probably not the answer you were expecting, but there’s that. Many of the poems I wrote as part of that “stupid exercise” actually became some of my favorites. I won’t name all of them, although they can be easily Googled, but “I Saw Owen Wilson…” is one of them.

I love that, though! What were the first and last poems you wrote that ended up in this collection? Can you identify anything that’s changed for you in your poetic ethos or stylistically between writing those two poems?

“Love doesn’t exist, change my view” is definitely the oldest by far. I think the newest is actually “I Nearly Had A Panic Attack While…” you know, the goblin one. Which I think says a lot. The main thing that’s changed over the period of time in which these poems were written is that I care a lot less about being capital-P Poetic than I used to. This is most likely due to a combination of leaving an academic environment and discovering a whole wealth of lesser-known indie poets (and prose writers too) online whose work absolutely punched my gut and yet seemed totally unconcerned with whether or not it was “doing enough” in terms of craft. That anxiety is something that informed — and still informs — a lot of my work; I don’t often feel like I can get away with just stating something the way I believe it should be stated. But in light of my handful of new influences and the fact that I now co-edit a journal that celebrates weirder, less traditionally capital-P Poetic work, I’ve allowed myself to have a little more fun. There are actual tweets of mine in this book, which is not something I would have allowed a year ago. I’ve been branching out even more since I finished this book. It’s been freeing to do whatever I want, stylistically, although I still have to remind myself it’s legal.

I’m glad that you’ve brought up your editorial work. Would you like to talk a little bit about the editorial work you do and about Philosophical Idiot?

I’m glad that you’ve brought up your editorial work. Would you like to talk a little bit about the editorial work you do and about Philosophical Idiot?

Definitely! So we’re an online literary journal and very, very baby, burgeoning small press. The journal is about a year old now, or will be at the end of the month, and I started working on it this past November. B. Diehl, the founding editor/other co-editor is my best friend and my partner. So, it’s really a labor of love for us.

We don’t really have guidelines, but in general we prefer weird and bite-sized. We take poetry and prose and whatever else doesn’t fit either of those two categories. We publish curated lists of tweets from other writers. One time we published a blackout poem of the Steamed Hams meme. But even these loose guidelines don’t account for the fact that we’ve also published some longer, more traditional poetry in recent memory as well.

B. and I have both heard people say that Philosophical Idiot has a 90s DIY sensibility which is insanely flattering, so we can also go with that. We accept submissions on a rolling basis forever and ever at aksdgjsghskgjddfv@gmail.com. Yes, for real.

As someone who works both in the creation and the publication of poems, where did your interest in poetry come from? How did it develop?

I really have been interested in writing forever. I guess that’s an easy answer, but I’ve never really been super interested in doing anything else with my time, even as a little kid. As for poetry specifically, I noticed that if I whined and complained about what was going on inside of my head, people weren’t very inclined to listen to me or tell me my feelings were valid. Put it into art, and something about the artifice of it makes people at least slightly more likely to listen and take you seriously. I still kind of believe that, though maybe not to the cynical extreme I did before. Most people aren’t very skilled at listening or empathy, and to be honest, I don’t think many people are interested in getting better at it. If you package your feelings or ideas in art, somehow it brings people’s walls down and makes it easier for people to grasp your experience. Mostly, I just want people to listen to me and understand what I mean.

Find out more at katgiordano.com, or follow her on Twitter @giordkat.