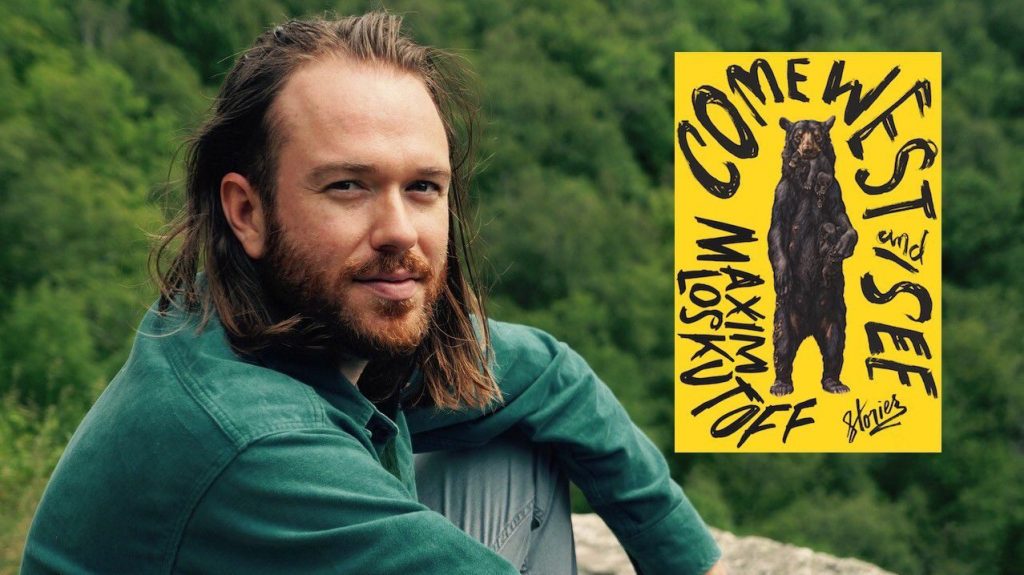

Making it from sunup to sundown without bending at the waist and retching into the nearest vegetation is no small feat this year. Every time public life and discourse seems to have careened into rock bottom, the rock gives way with a sickening yawp, revealing yet another level of horror and depravity and, once again, the hope that this might really be the worst of it, and that what comes next has to be at least a little bit better. Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, that fiction written for and about these times should move along at the same rhythm. That’s certainly the case in Come West and See (W.W. Norton, 2018), the visceral debut short story collection from Montana-bred writer Maxim Loskutoff, a graduate of NYU’s MFA program and student of both David Foster Wallace and Zadie Smith.

As Loskutoff describes it, Come West and See’s twelve stories are structured as “the ripples that flow outward” in concentric circles around a rock dropped into a pond. They certainly do ripple outward, but with much more violence than his description suggests. At the crest of each wave we see portraits painted in shades of fear, desperation, shame, and self-loathing, with little flecks of hope and promise when the sun hits them just so.

The rock Loskutoff drops in his pond is “The Dancing Bear.” Set in 1893 in the pre-statehood Montana wilderness, the story consists of a vignette from the lonely, grim, and deeply perverse life of Bill, an Odyssey-reading fur trapper who has spent a decade cutting his living out of the woods around his hand-built cabin. Rather than drive him toward any sort of introspection or noble communion with nature, however, Bill’s solitude ultimately leaves him struggling to conceal an erection after wondering to himself whether a massive grizzly bear has breasts beneath its fur. Waves of confusion and shame rightly follow, though, again, we know there are lows beneath rock bottom.

If “The Dancing Bear” leaves a deep impression, it’s that there’s something profoundly wrong here. Simply put, people should not work the way Bill does. He’s broken. And Come West and See’s driving concern is tracing the contours of that brokenness while navigating the constellation of themes Loskutoff conjures in the shape of his perverse woodsman. The image is clear enough, and should by now be all-too familiar: a white man trying to put his name on something — the West, nature, a woman — and burning everything to the ground in the process.

Rolling along through the book’s remaining eleven stories — and one rolls at a fast clip, given Loskutoff’s adeptly crafted plots, chock full of humdingers like our horny woodsman or a couple trying to escape a dystopian separatist colony while shot full of arrows — we see several portraits of the same character, albeit dressed in different costumes. He is, we can presume, a Trump voter. Though more specifically, he’s the sort of soon-to-be-Trump-voter who, in the winter of 2016, drove his pickup out to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, rifles in tow, to join up with the Bundy Occupation.

Rolling along through the book’s remaining eleven stories — and one rolls at a fast clip, given Loskutoff’s adeptly crafted plots, chock full of humdingers like our horny woodsman or a couple trying to escape a dystopian separatist colony while shot full of arrows — we see several portraits of the same character, albeit dressed in different costumes. He is, we can presume, a Trump voter. Though more specifically, he’s the sort of soon-to-be-Trump-voter who, in the winter of 2016, drove his pickup out to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, rifles in tow, to join up with the Bundy Occupation.

As Loskutoff explained, the Bundy Occupation led to Come West and See’s conception in a moment of sudden enlightenment. It happened to him at a bar in the blue collar town of Otis, Oregon, about an hour and a half away from Portland. Back in Portland, he’d spent his evenings surrounded by likeminded friends, cackling at videos of the Bundys’ supporters furiously hurling to the ground boxes of dildos sent by Internet trolls responding to their requests for food donations. At the bar in Otis, however, he found himself in the midst of an entirely earnest, “deadly serious” debate about the Occupation’s merits, nary a dildo in sight. It was as though History had grown an arm for the express purpose of slapping him upside the head: He became “sick to [his] stomach” upon realizing that by driving the hour and a half from Portland to Otis, he had inadvertently stepped over a lurching chasm between two Americas.

Loskutoff began writing the stories that would eventually comprise Come West and See shortly afterwards, thinking of them, he said, as a “warning” for the people back in Portland laughing at the Occupation through their laptops and smartphones. He wanted them to understand just how segregated life in the West and in America as a whole had become, and he wanted them to see that their version of “progress” or the American project was by no means universal.

Of course, by the time Loskutoff completed his manuscript, sending out a warning signal about that particular issue had already become something of a moot point. Beneath the ominous orange glow of Trump’s 2016 election victory, “Come West and See” almost invites comparison with books in the vein of Juan Rulfo’s enigmatic midcentury masterpiece Pedro Páramo, a surreal, macabre reflection on the Mexican Revolution. In both books, a series of small, sad, domestic storylines set against a backdrop of national tragedy converge for a moment, run parallel ad infinitum, or spin off into the nether while flitting freely between past, present, and future. And again, in both Pedro Páramo and Come West and See, the end result is a discomfiting, Cubist portrait of an inchoate, growling monster.

Loskutoff’s monster is the Bundy supporter — a small man raised on a steady diet of myths about his own bigness. The figure comes into focus perhaps most clearly in “Umpqua,” a study in self-loathing, projection, and the futile expression of masculine dominance through speed and aggression.

Russ, the narrator of “Umpqua,” brings his girlfriend Bun along on a sort of pilgrimage to a hot spring, which he conducts in honor of a friend who was killed by federal soldiers after joining up with a fictionalized version of the occupiers.

It quickly becomes clear that the trip is more than a pilgrimage, however. It’s also a referendum on Russ and Bun’s relationship. Naturally, all signs indicate he’s shitting the bed. The sticking point this evening seems to be Bun’s weight. She’s gotten much heavier in the years since they’ve started dating, and Russ’s response is an unpleasant melange of disgust and jealousy. She insists on skinny dipping at the springs and he can’t seem to settle on whether he’s more viscerally upset by the idea of another man seeing her naked, by the idea of people laughing at her weight, or by the fact that he’ll have to see her naked himself. Regardless of which issue is more salient, all three are true and, needless to say, none of them win him any points with Bun.

Per schoolyard logic, it’s a fragile, empty ego that props itself up and fills itself out by keeping others down. And in typical schoolyard bully fashion, as soon as Russ realizes nobody’s listening to him anymore, he throws a temper tantrum, albeit in the loudest, most explosive and self-destructive manner available to man of his modest means. The horror of “Umpqua,” however, is that Russ’s tantrum means nothing and goes nowhere. After the smoke clears, he’s just as bitter, small-minded, and oppressive as he was before.

In that sense, Come West and See differs in tone from a book like Pedro Páramo. Whereas Rulfo’s novel is full of corpses, Loskutoff’s characters are very much alive, and one of their East Coast cousins is now an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court. His book thus retains echoes of the warning call he originally hoped it would sound, though the warning is different. Now we know there’s another America just down the road. The question is, what are we going to do about the monsters that live there?

The following is taken from a conversation on this and other questions raised by Come West and See, edited and condensed from a phone interview with Loskutoff.

The first story in the book, “The Dancing Bear,” is positioned as a prelude to the other stories in several different ways. It’s the first story in the collection, of course, but it’s also set in the same location as the other stories, more or less, but in 1893, a period of time that precedes or perhaps gives rise to the modern society that the rest of the stories depict. It clearly foreshadows many of the themes we see in the rest of the stories as well — solitude, male characters who are ashamed of themselves in a certain ways, yet still have a sense of entitlement with regards to the environment around them, violence, the relationship between sexuality and violence, et cetera.

You’re absolutely right. I wanted this story to be like the rock that’s dropped into the pond, and the rest of the stories are the ripples that flow outward. It was important to me to show that the futility of this kind of masculinity that the characters have in the stories that are set in the present day isn’t a new phenomena — it’s been true of Europeans’ place in the West since the very beginning.

So yes, again, I wanted that story to establish the sort of paradox that has been at the heart of the American West and the culture out there. This desire of the wild landscape that drew you there — you left the cities of the East or whatever country you came from and you came there for the promise of this wildness and this freedom, but once you got there you wanted to tame it and carve out a piece for yourself. The way that the protagonist of that story sees … essentially what he wants to do with that bear is tame her and make her his wife in some kind of crazed way so that they can raise children together. But the reality of that, of course, is that it’s completely impossible, and even if he did manage to tame this bear, he’d lose that thing about her which initially drew him to her. So that kind of futility is, I feel, the same kind of futility that’s at the heart of the militiamen that are out in the West right now, the ones that some of the characters in the book are based on.

Considering that idea of broken foundations, I’m interested in the way this story relates to Literature with a big ‘L.’ This collection isn’t self-conscious of its literariness. You don’t write much about writing, or reflect on literature as such. But “The Dancing Bear” has, I think, the only reference to another piece of writing in the book — Bill the trapper is a reader of Greek epic poetry, and particularly the Odyssey. As you mentioned, the history of the West and Europeans’ place in the West involves so much going out into the wilderness and taking something for yourself. You don’t normally think of Greek epics through that lens, and yet the Odyssey is the next chapter of the Iliad, which, despite having all of these heroes and gods and tragedy, is ultimately a story about going overseas to sack and pillage a foreign country.

I was always struck by how in those Greek myths, and canons all across the world, there’s so little self-questioning. To me, that’s sort of the great flaw, or also just a fascinating aspect of masculinity that stretches throughout history. You go out and you either pass the test and get what you want, or you don’t pass the test and return home with nothing. But there’s never this moment of, like, “Why?” You know, “Why did I leave my wife?” “Why did I do all this shit?” I feel that most of the characters I write about are that same kind of character. Some of these stories I put from the woman’s perspective even though my project is very much trying to figure out this kind of masculinity in the West.

But most of the men I write about wouldn’t be able to speak about it themselves. They don’t question, you know. That’s, I think, a great challenge for me trying to write literary fiction about the kinds of people I grew up with. This desire to give the story the kind of questioning and opaque aspects that make literary fiction what I love more than anything else in the world. But my characters … I know these guys, they set up their entire lives to not do that. That’s one of the great challenges of the book. And I think you’re right, this isn’t a book about voracious readers, so I think that’s the only reference to another book in the whole thing. I think that’s meant to be a nod … this is a book about the American West, but those ideas are so much older. This idea of going out and plundering without thought, that’s one of the oldest stories of mankind.

I’m surprised to hear you say that your characters don’t really think or question what they’re doing, though. I agree they often don’t seem to question why they’re in a certain situation that they’re in — although your women characters certainly do — but the men are thoughtful, albeit in a self-abasing way. Many of them are deeply ashamed of themselves and constantly ruminate on that shame. Can you elaborate on where you see the distinction between questioning what you’re doing and the self-questioning that your characters engage in?

I didn’t mean they don’t question themselves, I meant rather that they’re unable to place themselves within these larger questions of masculinity or what it means to be a person in the West right now. For me, I think the distinction is that the men I write about are almost obsessively aware of their own failings and the ways that society has failed them, but they aren’t able to put that into a context that could be useful.

But you’re absolutely right, this is a seed of so much of the darkness in this country right now. There’s an incredible amount of self-loathing that’s being turned outward, a generation of young men in the West — though as I’ve done reading in other parts of the country, everywhere I went people would say, “Oh, that’s exactly like my hometown in New Hampshire,” or “That’s like this little town I know in Pennsylvania.” These places where the cultural identity of the place has changed. The town I’m from when I was little was a mill town, but by the time I was in middle school, both the mills had closed. Now, it’s basically a tech and university town. So you have this generation of guys my age, in their early thirties now, whose dads were loggers and whose moms were often also loggers or employed by the logging companies, whose entire identities were tied up in this culture that is now gone. And then the kind of work that has come in to replace it, they’re not qualified for, or they don’t even want to do it. So they end up working in gas stations or being forced to move far out into the country. The result is this flailing anger.

This anger goes both back in at themselves, for not being able to find a place in the modern world or an identity that they can be proud of, but it also zooms out at everyone else — that it isn’t exactly their fault. It must be someone else’s. That was one of the great challenges of writing a fictionalized version of the Bundy Occupation in Oregon. The Bundys were at the top — these ranchers that had hundreds of thousands of acres, tens of thousands of heads of cattle — people who had a reason, even if the reason was stupid, to want to be in conflict with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). But most of the guys who came out to follow them are the guys I was interested in. They’re from a trailer park in Tucson, or some little town. They don’t own any cattle, they’ve never interacted with the BLM, and might not even really know what the BLM is if you talk to them. These guys have a zillion different personal grievances and reasons to be out there.

This is not a flattering story collection by any stretch of the imagination. It’s hard to say if there are any good characters in this, people who you would say unequivocally, “Oh, that’s a hero.” Maybe an exception would be “Stay Here,” which depicts a couple that have had issues with infidelity, but seem to be working through them in a mature and self-aware fashion. And certainly, the writing in that story is some of the more sensitive in the collection. What is it about these characters and this story that warrants a more sensitive treatment than some of the others?

There is a sense to that — I would add that Carsten and Sarah in “Come Down to the Water” are meant to be good people — but “Stay Here” was meant to be the anomaly in the book, or the hinge around which the rest of the book swings. It comes right in the middle and right before the occupation lurches into a state of extreme but very isolated violence.

The point of the story was to show how difficult it is, no matter who you are — I mean, the book isn’t meant to be just about angry, disaffected people from rural communities. Half the stories are about people in cities or in urban centers of the West who are only kind of glancingly aware of the anger and the occupation that’s going on around them. “Stay Here” is meant to be the center of that, a couple that escapes and goes to the Midwest, to Michigan, to try to make another type of life for themselves and succeeds, but is haunted by the specter of this violence and the anger in this country. To me, that story is about how hard it is for anyone to find a place in America.

There is so much darkness in our history that’s bubbling up right now. For me, we are all a part of this country, and we’re all a part of the history of genocide, all our cities are built on death and the destruction of one country. It’s something that all of us are perhaps at least subliminally a part of, and at some level you have to reckon with it. That’s not to say that you can’t live a beautiful life and have children and find happiness, but as happens in that story, that darkness is always there.

And certainly the characters in that story are clearly haunted by the fear of violence, by fear of the other, or by the suspicion that the person you run into on your way to a restaurant isn’t actually on your side. The way “Stay Here” plays with that dynamic is interesting. The other stories in the collection are mostly about men living in the West who are very aware of the disrespect they feel others have toward them and resent, if not “coastal elites,” then at least people with an education, with gainful employment, who seem to have some role to play in the larger society. In “Stay Here,” we see a portrait of the object of that resentment, and in some ways the portrait confirms those men’s fears. The couple do view these small-town people with a degree of disrespect — the husband sort of cruelly makes fun of the waiter at the only restaurant in town.

That’s really the reason I wrote the book. For years, and I’m sure you know this feeling, when you’re starting out as a writer you spend so much time thinking over and over again, you know, “What is it that I have to say that hasn’t been said before?” The idea of putting this book together came when I was living in Portland, Oregon. It was when the Malheur Occupation began, when these guys went out with their guns and took over a bird sanctuary — which I had been to, as it happened, so I knew exactly how far up in the middle of nowhere it was. Everyone up around me thought it was the most ridiculous thing in the world, you know? We were getting our news from Gawker, where they were posting videos of people sending them dildos when they asked for snacks, and they would post a video of one of the occupiers sweeping them angrily off a table. Everyone thought that was hilarious. That was really my full reaction to the event — it was completely ludicrous and the government needed to go in there as quickly as possible and get those guys out of there, whatever the cost.

Then, about halfway through the occupation I moved out to a small town on the Oregon coast, a kind of a blue-collar town where there still was a mill. I remember the first night I was there, I went out to a bar and everyone was talking about the occupation. There were people who agreed and people who disagreed, but everyone took it deadly serious. Nobody could even imagine … I took the title of “Daddy Swore an Oath” from these parody videos that people were making — one of the occupiers had a made a video the night before he left telling his kids why he wouldn’t be home for Christmas, and it was this very dramatic, very heartfelt, very ridiculous, but also very beautiful thing, in a way. For me, I remember going home after that first night and feeling sick to my stomach that these two places that were only about an hour and a half apart — this little town and Portland, Oregon — could look at the same event and view it so differently that they actually had contempt for the way that the other people reacted to it, that they’d gotten so far apart and that gulf had widened so much.

I started realizing that there were examples of this over and over again in my life, because I’ve spent my life going back and forth between where I’m from in Montana to living in big cities on the coast and around the world. It was this “Oh shit” moment of how big that gulf had gotten. So I started putting these stories together almost as a warning, to try and show just how one event can be viewed so differently, and how these people can simultaneously have so much disdain for one another despite living so close together. The West and so much of this country has gotten so segregated that you can go your whole life living totally separated from people who think differently from you. So I wrote it sort of as a warning, thinking that when it came out the Bundys would be in jail and Hilary Clinton would be President. But it turned out that a lot of this stuff was much closer than I could have imagined.

Moving on from there, I wanted to discuss the women characters in your stories. In “Daddy Swore an Oath” and “How to Kill a Tree,” you see examples of women who are in committed relationships and are taking stock of their lives, trying to understand why they are where they are. They’ve been placed into stressful circumstances, but in comparison with your male characters who, as we discussed, have difficulty questioning their role within larger narratives about life in the West, your women characters seem to address those questions more explicitly. Could you talk a bit about what differences you see there?

When I was following the Bundy Occupation — after seeing how different the reaction was to those events in Portland versus Otis, Oregon — I started sort of obsessively following the occupiers in the way that you can in this modern world. You can stalk them on social media, follow them on Facebook and Twitter, blah blah blah. And what I quickly became almost more interested in than the men that were out there was their families, and their wives in particular, who they left behind and were trying to take care of their kids and keep the house together, and who were facing this very real possibility that their husbands might never come home, that they might be killed out there. In every instance, the husbands very proudly said how ready they were to die for this cause. I became fascinated by the fact that for these wives, there isn’t the option of this grand gesture, of saying “I don’t appreciate how my life is so I’m going to go out into the woods with guns and take this place over.” It’s more like, “I have two kids who are tiny and need to eat.”

They might agree with the reasons their husbands went out there, but they need to deal with life. That gives them a window — you know, there’s a necessity of evaluating what’s really worth it. What’s worth it in the lives of their children, and where do their values run up against the necessity of everyday things? Those are the windows I’m most interested in — these moments of incredible complexity where you love your husband and believe in what he’s doing, but at the same time have to ask, you know, “Why aren’t you here? We have a life. We have to survive, we have to go on.”

But beyond that dynamic, I would say that this dissatisfaction and difficulty with finding a place in life in the modern West — it’s not a gendered issue. Everybody’s feeling it. The young wife in “Ways to Kill a Tree” is feeling it in a very similar way that a lot of the male characters are in these stories. But at the same time, I think it’s easier to have a more nuanced reaction to it when you’re forced to look at it in a much deeper way by having a life and a home outside of yourself that you have to protect. So, yes, the women characters in this book, they have their own internal struggles but are also observing the futility and ridiculousness of the men around them, who are by and large flailing unthinkably.

Find out more at maximtloskutoff.com.