- The Past Isn’t Past

One of the last poems the Hungarian poet Miklos Radnoti wrote before he was murdered is the short “Postcard 3.” One of millions who died during the Holocaust, Radnoti was shot in early November 1944, following a forced march; “Postcard 3” was written during the march. Here it is in full:

Bloody saliva hangs on the mouths of the oxen.

Blood shows in every man’s urine.

The company stands around in wild knots, stinking.

Death blows overhead, revolting.

Mohacs, 24 October 1944

The poem is striking in its economy. The first three lines are compact, evocative images, while the fourth is a rejection of the whole scene, and of the poet’s situation. Moreover, the poem’s title drips with cynicism; one tends to send postcards from nice places. It is an angry, raging poem. And though its speaker isn’t shown, one can imagine him shaking his fist at everything around, at the oxen, the men pissing red, the stinking company standing in knots. Radnoti was only thirty-six when he died. The “Postcard” poems — and indeed all of Radnoti’s Holocaust work — thrum with the circumstances in which they were written. While reading “Postcard 3,” one cannot avoid that Radnoti was killed only days after writing it. A sense of present horror — this very minute, under your nose — abounds.

Demian DinéYazhí’s art aims for a similar immediacy. DinéYazhí, whose work interrogates colonization and repression, wants their audience to be uncomfortable. They want their audience to acknowledge, to paraphrase Faulkner, that the past is not past, and that the correct tense to use when discussing America’s mistreatment of Native peoples is present, not past: is, not was. And DinéYazhí is not subtle about it. For example, the video By Entering This (Indigenous) Space… includes the following instructions:

From this moment onward you have agreed to learn

the history of the Indigenous ancestral lands

that were stolen & continue to be stolen

through settler colonial violence

& environmental genocide.

These instructions, which I read standing before a monitor, are not directed at an abstract viewer. The words are directed at you, you standing right there. They are poking you in the chest, demanding that you listen up, pay attention now, hear?

Born in 1983, DinéYazhí grew up in Gallup, New Mexico and is a member of the Diné (Navajo) clans Diné Naasht’ézhí Tábąąhá (Zuni Clan Water’s Edge) and Tódích’íí’nii (Bitter Water). DinéYazhí’s art dismantles ideas of colonization, Western assimilation, and genocide, and it’s shared through traditional outlets such galleries and museums as well as the Internet: DinéYazhí publishes a blog, an Instagram account, and a YouTube channel. They also run an Etsy shop where they sell T-shirts with slogans like “Radical Indigenous Queer Feminist” and “Respect Indigenous Uprising.”

Much of DinéYazhí’s work — videos, slideshows, individual images — employs text that confronts its audience. This text is an intriguing mix of political and evocative personal content, dealing with Native colonization, environmental criminality, queer intimacy, and identity; experiencing DinéYazhí’s art is like having someone simultaneously stroke your head with one hand while they punch you in the gut with the other. DinéYazhí is both a visual artist and a poet, and they use the sharpest tools of both trades. A representative piece is American Bondage West, which comprises text over images of human and natural landscapes:

- Eat, Consume, Colonize

DinéYazhí’s work is currently on view at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, the latest installment in the Henry’s Brink Award series. DinéYazhí’s Henry show is made up of six presentations (including the aforementioned American Bondage West), one sculpture, and two videos, By Entering This (Indigenous) Space… and a companion video called ANCESTORS RISING that uses footage of the Indians of All Tribes’ 1969-71 attempted reclamation (or occupation, depending on perspective) of Alcatraz Island. Everywhere one looks in DinéYazhí’s show, they encounter ever-changing imagery and words. Even the lone sculpture moves: in neon, the words “in beauty / it is restored” flicker on — in beauty—it is restored — and off around a circle. It is a restless show.

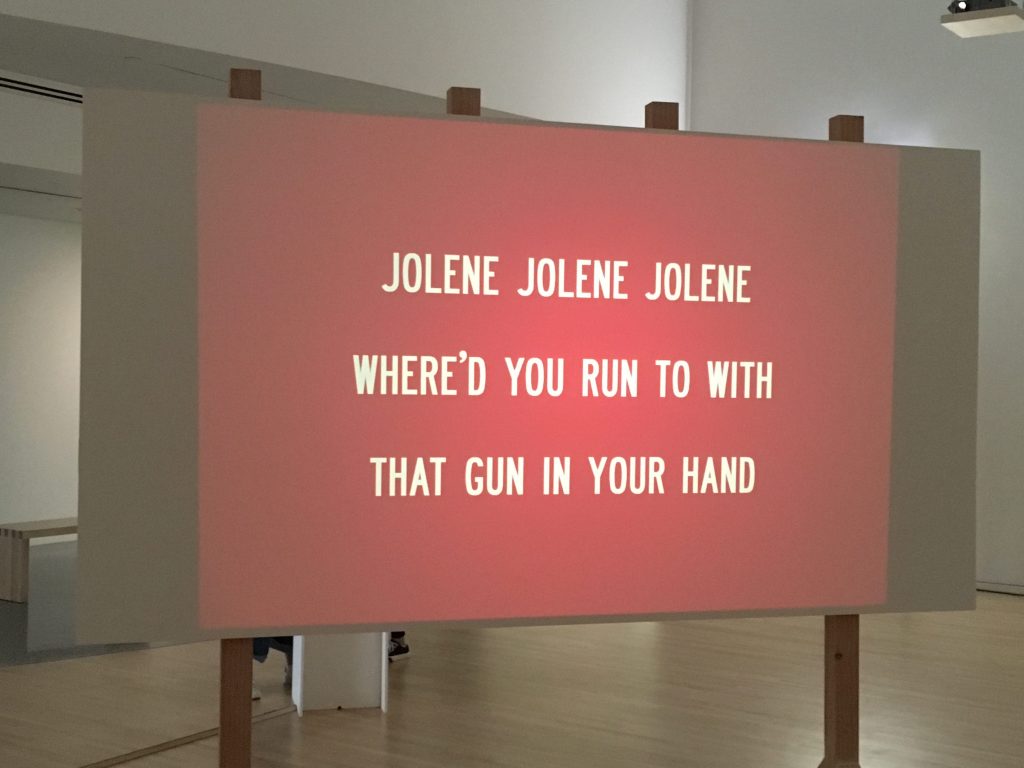

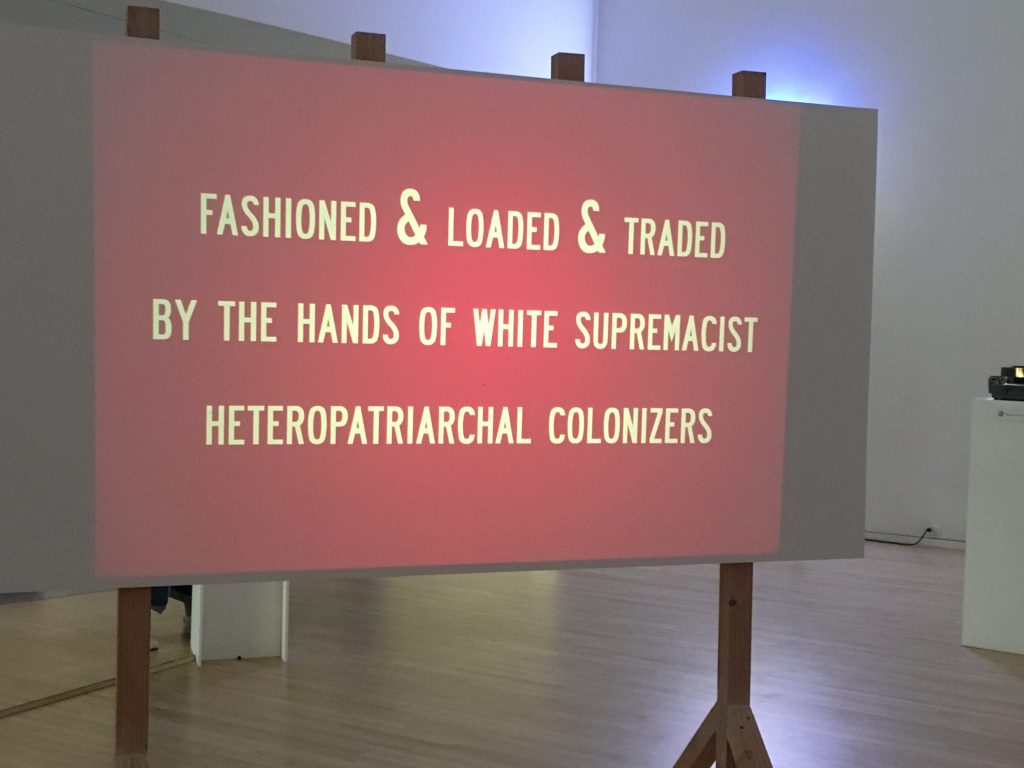

All but one of DinéYazhí’s slides include imagery as well as text. The one projection that forgoes imagery, the stark HEY JOLENE, tucked in a corner of the exhibit, shows the degree to which DinéYazhí’s imagery softens their words. Even compared to the rest of the pieces, the palette of HEY JOLENE — white, all-caps words on a red background — positively shouts at its audience. The text of one slide reads: JOLENE JOLENE JOLENE / WHERE YOU’D RUN TO WITH / THAT GUN IN YOUR HAND. Says another: FASHIONED & LOADED & TRADED / BY THE HANDS OF WHITE SUPREMACIST / HETEROPATRIARCHAL COLONIZERS.

All but one of DinéYazhí’s slides include imagery as well as text. The one projection that forgoes imagery, the stark HEY JOLENE, tucked in a corner of the exhibit, shows the degree to which DinéYazhí’s imagery softens their words. Even compared to the rest of the pieces, the palette of HEY JOLENE — white, all-caps words on a red background — positively shouts at its audience. The text of one slide reads: JOLENE JOLENE JOLENE / WHERE YOU’D RUN TO WITH / THAT GUN IN YOUR HAND. Says another: FASHIONED & LOADED & TRADED / BY THE HANDS OF WHITE SUPREMACIST / HETEROPATRIARCHAL COLONIZERS.

At the bottom of the exhibition’s description placard, below the artist bio and curator’s note, set apart in its own paragraph, is the following disclaimer: “The Henry and the artist acknowledge that we are situated on the land of the Coast Salish peoples.” The implication is that the viewer, by being in the Henry, is complicit in the occupation of the Coast Salish peoples’ home.

Interestingly, despite how arresting — loud, if you will — its content may be, DinéYazhí’s Henry exhibit is hushed. Between the hum of the slide projectors’ fans and the shuffled clicking of their trays, the exhibit has an academic feel. Combined with the gallery’s deep quiet, the slide projector sounds give the work a didactic, instructive air; standing amidst DinéYazhí’s work at the Henry, one feels they are being lectured to. The slides tell but they do not converse.

Interestingly, despite how arresting — loud, if you will — its content may be, DinéYazhí’s Henry exhibit is hushed. Between the hum of the slide projectors’ fans and the shuffled clicking of their trays, the exhibit has an academic feel. Combined with the gallery’s deep quiet, the slide projector sounds give the work a didactic, instructive air; standing amidst DinéYazhí’s work at the Henry, one feels they are being lectured to. The slides tell but they do not converse.

But why should they? By producing work that lectures but does not necessarily converse with its viewers, DinéYazhí offers visitors a taste of Native peoples’ colonial experience: forever on the receiving end of (often unsolicited) information, of change, of aggression. Moreover, the work reflects DinéYazhí’s own experiences. Indeed, images of their body (hands, tattoos) recur in several pieces, and the combination of personal and political imagery and text makes the unapologetic case that political questions cannot be separated from the personal. For example, well before American Bondage West addresses colonization and “THE POLITICS OF SURVIVAL,” it begins with the following lines: “THE CURVE OF AN ARMPIT / IN THE EARLY MORNING.” The latter line is superimposed over an image of a nude male torso, with both of his arms up.

And then there is DinéYazhí’s book-length prose poem An Infected Sunset, which they wrote in response to the “Orlando nightclub shooting, police killings of unarmed Black men, and in the midst of the Standing Rock #NODAPL Resistance.” Where DinéYazhí’s visual art weaves the personal with the political, establishing a wavering link between the two, the more verbose An Infected Sunset makes that connection explicit. It is a screed, by direct way of DinéYazhí’s lived experience, and “I” appears frequently. Here’s a sample, from a performance DinéYazhí gave at the Whitney:

Over one hundred million indigenous people killed. Allow me to help you imagine that number: imagine that every person who has ever owned a Tina Turner, or Adele, or Britney Spears, or David Bowie album dead, annihilated because of colonial dumbfuckery European curiosity. I should be at Standing Rock with thousands of other indigenous activists, with the other indigenous tribes standing in solidarity against a white snake with black blood trying to fuck shit up like a science fiction horror story, except this time the indigenous people aren’t stereotyped as cannibal savages threatening white tourists looking for a little bit of culture, looking for something to discover, looking for something new to eat consume colonize repeat, eat consume colonize repeat, colonial dumbfuckery European curiosity. The other night I walked to the nearby 7-Eleven and came across two indigenous folks. While standing in line, I noticed the sister with a streak of pink hair wearing beaded earring, so I asked them what tribe they are from.

As the saying goes, the personal is political. In DinéYazhí’s case, it is also radical, indigenous, queer, and confrontational. Their art is uniquely suited to respond to — and rebel against — our time, and we are lucky to have it.

Notes

- “Postcard 3” is from Radnoti’s The Complete Poetry, translated by Emery George, Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis, 1980.

- DinéYazhí’s show at Henry Art Gallery will be on view until September 9, 2018. Visit henryart.org to learn more.

- Lead image includes still from DinéYazhí’s American Bondage West. Photo of DinéYazhí is courtesy of the artist. Inset exhibit photos were taken by the author.