Heroes, behold your King—

Slow as an arrow fired feathers first

To puff another’s worth,

But watchful as a cockroach of his own

Aggrieved Men, Aggrieving

The last year and a half, since Trump’s poorly attended inauguration, has been anything but quiet; the apocryphal “may you live in interesting times” applies. It’s been hard to keep up! A lot has happened, especially on Twitter! How is one to make sense of the lunacy? Perhaps the Iliad can help.

To be specific, Christopher Logue’s version (i.e., non-translation), War Music. Comprising five volumes that retell thirteen of the Iliad’s twenty-four books, War Music was Logue’s best-known project and spanned more than five decades; it was incomplete upon his death in 2011. What Logue did complete — Kings (books 1-2), The Husbands (3-4), All Day Permanent Red (5-6), Cold Calls (7-9), and War Music (16-19) — ranks with the very best translations of the Iliad. Here’s Logue’s take on Achilles’s grief (Book XVIII) versus Richmond Lattimore’s translation:

LOGUE:

Down on your knees, Achilles. Further down.

Now forward onto your hands and thrust your face into the filth,

Push filth into your open eyes, and howling, howling,

Sprawled howling, howling in the filth,

Ripping out locks of your long redcurrant-coloured hair,

Trowel up its dogshit with your mouth.

LATTIMORE:

He spoke, and the black cloud of sorrow closed on Achilleus.

In both hands he caught up the grimy dust, and poured it

over his head and face, and fouled his handsome countenance,

and the black ashes were scattered over his immortal tunic.

And he himself, mightily in his might, in the dust lay

at length, and took and tore at his hair with his hands, and defiled it.

Though Logue’s work is a departure from traditional translations of the Iliad, the story is the same: the Iliad / War Music is about a handful of aggrieved men aggrieving each other.  Nominally, its story is of a war fought between the Greeks and the Trojans (Ilium) because Paris, a prince of Troy, stole Helen from Menelaos, the king of Sparta. But the Iliad is also about Agamemnon (king of Mycenae) vs. Priam (king of Troy); Achilles (chief Greek hero) vs. Agamemnon; and Achilles vs. Hector (chief Trojan hero). Above and behind these aggrieved men are various gods vying with one another, either because they love Greece or Troy qua Greece/Troy, or hate specific Greeks or Trojans.

Nominally, its story is of a war fought between the Greeks and the Trojans (Ilium) because Paris, a prince of Troy, stole Helen from Menelaos, the king of Sparta. But the Iliad is also about Agamemnon (king of Mycenae) vs. Priam (king of Troy); Achilles (chief Greek hero) vs. Agamemnon; and Achilles vs. Hector (chief Trojan hero). Above and behind these aggrieved men are various gods vying with one another, either because they love Greece or Troy qua Greece/Troy, or hate specific Greeks or Trojans.

In short, the Iliad / War Music is about a series of individual conflicts that spur other individual conflicts as well as broader fights. Which sounds awfully like geopolitics in 2018, at least as they’re practiced by a handful of leaders. Trump may be the most carbuncular example, but he’s hardly alone. The Iliad model of international affairs — tough guys bumping chests — is hardly a thing of the past.

To wit. According to “The 21st Century Individual in International Affairs,” published in Global Brief by UT Austin’s Jeremi Suri, “the recurring international crises of our time are driven by leaders with unprecedented technological capabilities at their disposal.” Furthermore:

The contemporary international system is defined by powerful individuals in state and non-state positions. It is also defined by the constant shifting of attention and legitimacy among these individuals. One week’s charismatic celebrity is another week’s discredited dissident.

The article, which was written in 2013, shows its age: it cites “Gangnam Style” — the video for which has 3+ billion views on YouTube —and is (sadly) sympathetic toward Julian Assange, a heliophobic whitehead in human form. But Suri’s thesis has proven prescient, and Trump is the proof.

Since he took office, Trump has undermined and/or wounded institutions and norms around the world; that nothing calamitous has happened seems more like luck than anything. Likewise, in the Iliad / War Music, Agamemnon, the most powerful Greek king, destroys Greek unity when — in a capricious moment of entitlement and arrogance — he insults Achilles, which leads to “pains thousandfold” for the Greeks, according to the Lattimore translation. And on and on. The parallels between the Iliad and what counts as the news these days are legion.

Frequent Temper Tantrums

Having children means accepting the presence of strange things in your life. You support obsessions with crabs and scorpions. You say things like “take off your cape, it’s time for bed.” And you get used to temper tantrums. Specifically, you grow accustomed to (if not accepting of) the insanity and uncertainty that temper tantrums bring; one minute everyone in the house is yelling and you’ll agree to anything to make it stop, and then next your son has changed his mind and entirely forgotten that he cared so much about what caused the tantrum.

Such is the baffling experience of living in Trump’s America. Indeed, per USA Today, the mother of a fourteen-year-old victim of the recent Santa Fe, Texas school shooting said speaking with Trump — who “repeatedly used the word ‘wacky’ to describe the shooter” — was “like talking to a toddler.” In addition to speaking like a child, Trump is obstinate and mercurial (also like Achilles, but more later).

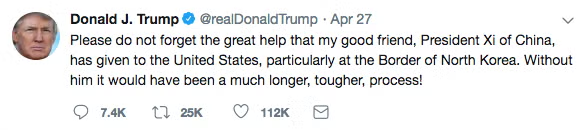

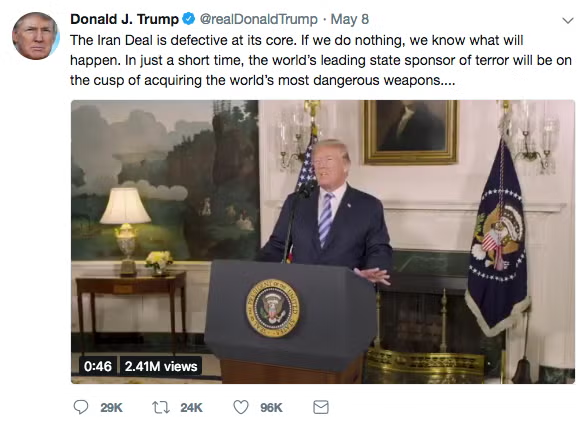

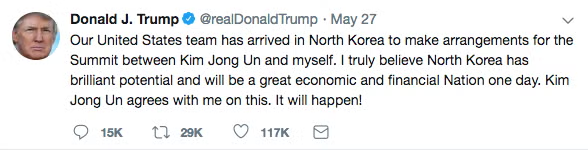

For example, here’s is a recent selection of the President’s tweets about the on-again, off-again summit with North Korea. Which show succinctly the degree of uncertainty Trump has injected into international affairs, which weren’t crying out for a shot of uncertainty. International affairs are not an aging marriage. They don’t need to be spiced up. The world is plenty spicy.

In the Iliad / War Music, much of the story is driven by a single conflict: after losing one of his captive women (the Iliad is among other things a story of male sexual dominance), Agamemnon takes Achilles’s most prized “she” (per Logue), and Achilles, insulted, sulks in his tent and refuses to fight for the Greeks. Achilles’s absence on the battlefield leads to a number of things: the Greeks fight among themselves; the emboldened Trojans leave their walls to whomp the Greeks; Achilles’s companion/lover Patroclus dons Achilles’s armor to push the Trojans back, only to be killed in battle; and Achilles, moved by grief and rage, rejoins the battle, leading to the Troy’s fall and, eventually, his own death. Achilles’s self-centeredness causes others to take action, leading to tragedy. He is, to use an overblown buzzword, a disruptor.

As in the Iliad / War Music, Trump’s volatility and narcissism has empowered similarly minded would-be disruptors; like children, they think he got his way so I want to get mine! Benjamin Netanyahu is one example, for the day after Trump withdrew the US from the P5+1 Iran agreement:

Israel carried out a series of strikes against Iranian targets in Syria, killing 23 fighters, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. Israel said that the assault, its largest inside Syria since the 1973 war, was in response to Iranian rockets fired at the occupied Golan Heights, although none had hit their targets, and there were no casualties.

Pick, Pick Up, Put Back, Pick up Again

I recently saw former ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul speak about his new book, From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia. The book is McFaul’s take on how current US-Russia relations were shaped by animus between several great men and women, and it was an extremely interesting event. When I saw him speak, McFaul said something to the effect of (I’m paraphrasing), “Putin’s a paranoid guy, and he believes that he’s in an ideological struggle with the West; it’s him versus Western excess and decadence.”

McFaul also commented briefly on Trump’s belief that, as McFaul sees it, good personal relationships with foreign leaders — not policy gains or concessions — are the main goal of international relations. In other words, Trump practices realpolitik on a one-on-one, individual level, without the constraints of silly things like “guiding principles” or “honor.”

Which made me think of the following speech from War Music. In Kings, after Achilles has been insulted and is refusing to fight for the Greeks/Agamemnon, Nestor — the king of Pylos and the oldest and wisest of the Greeks — visits Achilles in an attempt to reason with him. Achilles says:

‘Shame that your King is not so bound to you

As he is bound to what he sniffs

‘Here is the truth:

King Agamemnon is not honor bound.

Honor to Agamemnon is a thing

That he can pick, pick up, put back, pick up again,

A somesuch you might find beneath your bed.

Do not tell Agamemnon honour is

No mortal thing, but ever in creation,

Vital, free, like speed, like light,

Like silence, like the gods,

The movement of the stars! Beyond the stars!

Dividing man from beast, hero from host,

That proves best, best, that only death can reach,

Yet cannot die because it will be said, be sung,

Now, and in time to be, for evermore.’

Achilles criticizes Agamemnon for having no honor — implying that he, Achilles, is honorable — but this is a matter of perspective. From many Greeks’ point-of-view, Achilles is the one in the wrong, because the king is inherently right. And even if the king views honor (which Achilles sees as something above men, “vital, free, like speed”) as something “he can pick, pick up, put back, pick up again” as needed (such as when the king wants to make nice with someone who may not have the king’s country’s interests at heart), it doesn’t really matter, because might makes right, right? Sound familiar?

At any rate, how did things turn out for the squabbling, aggrieved heroes of the Iliad / War Music? What lessons, if any, can we learn from them? Let’s check in:

- Achilles: Dead, killed by Paris.

- Agamemnon: Upon his return home, he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, in revenge for Agamemnon’s sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia at the start of the war.

- Hector: Dead. After Achilles kills Hector, he dragged Hector’s body behind his chariot.

- Menelaos: Menelaos and Helen returned to Sparta, where they were unhappy.

- Paris: After he kills Achilles, Paris is killed by the Greek archer Philoctetes.

- Priam: Murdered as he begged for his life on the altar of Zeus.

Few lessons indeed. November is only a few months away; make sure you’re registered to vote.

Header image via Wikimedia Commons. Introductory epigraph taken from War Music: Kings.