At eighty-three years old, Richard Hunt still works almost every day in his studio in Lincoln Park — a cavernous, mid-twentieth century power substation for the Chicago Transit Authority. In 1971, when Hunt first acquired the industrial-looking structure, the area was far less tony than it is today; even now, passersby cannot likely imagine the miracles of modern art that have been crafted within its towering, red brick walls. Hunt’s metalwork — to which he’s dedicated his career — perfects a unique method of crafting lyrical, abstract, and often heroic sculptures that express the visceral connection between humanity, nature, and the built urban world.

In his illustrious and prolific career, Hunt established himself as very possibly the most productive public sculptor in the United States. His more than 125 public sculptures grace everything from the grassy sweeps of idyllic public parks to the imposing facades of steel and glass skyscrapers. He has been commissioned by corporations, hospitals, museums, municipalities, universities, and athletic organizations. One of his proudest recent accomplishments is the welded bronze sculpture Swing Low (2016), which hangs in the lobby of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, the newest Smithsonian institution.

Despite all he has accomplished, Hunt shows no signs of slowing down. On the snowy April day when I visited him in his studio he was busy working on a pair of 1:12 scale models for two massive stainless steel sculptures that will be installed in October 2018 in front of the redesigned Krasl Art Center in St. Joseph, Michigan. When completed, these lyrical works will strive upward in elegant, gestural waves, their shining boughs nearly intertwining, creating a fantastical archway under which inspired visitors will pass.

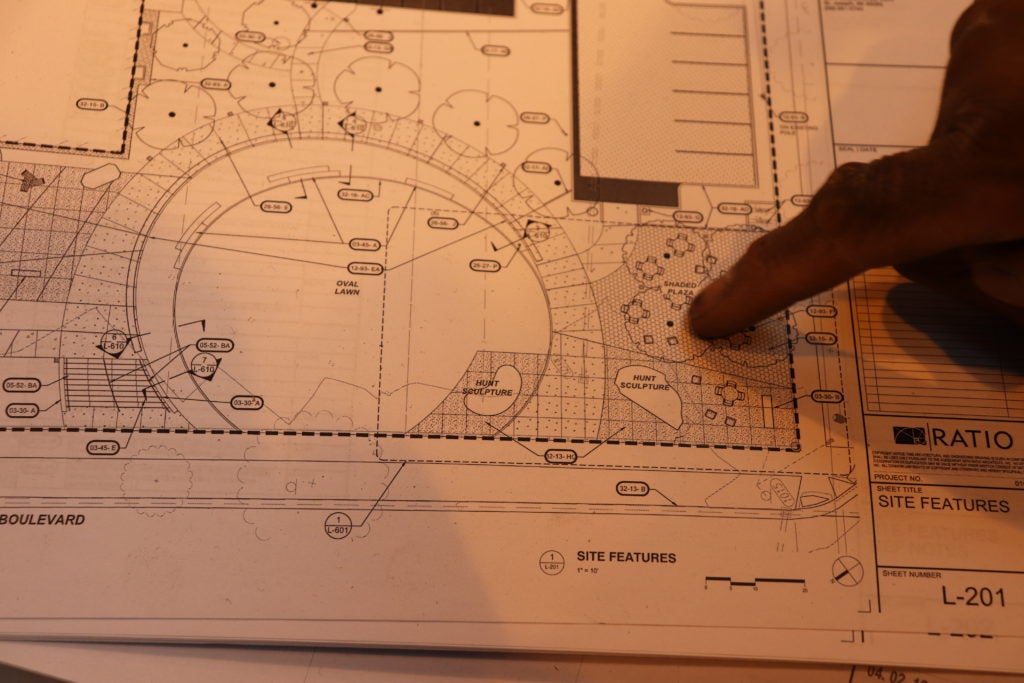

Looking over the blueprint for the site, I asked Hunt what he intends to title the work. Though still undecided, he says, “I’m thinking about Wavelengths.” Since the art center faces out to the shore of Lake Michigan, I ask if that offers one possible elucidation of this idea. Hunt says yes, then offers several more: “Air waves, brain waves, sound waves, electrical waves.”

I switch my camera on as Hunt bends down to look more closely at one of the models. He grabs onto the corner of an arching sliver of steel, bends it with his hands, then stands back to look. He picks the model up and carries it across the studio towards a work bench. “Follow me,” he says. I pause my recorder and settle in to watch as he negotiates with this renegade aesthetic element.

He grabs a piece of cardboard from a stack of cardboard scraps piled into a nearby box. He holds the piece of cardboard up to the spot on the model where he’d just bent the metal, then takes scissors and starts fashioning a new form from the cardboard, a sort of gently arching branch. Again, he holds the cardboard branch up to the sculpture and now I can see what he saw in his mind’s eye — the one, nuanced additional element that was needed to bring life to the work. He signals to one of his two longtime assistants to help him. The assistant swiftly produces some painter’s tape and tapes the cardboard extension onto the model. Hunt steps back and looks, makes a couple more snips with his scissors, then steps back and looks again.

“This is how it always starts,” he tells me, “with a piece of cardboard.”

Satisfied, he detaches the cardboard piece from the sculpture, picks up a marker, and tells me to follow him again. We walk to another work area where a massive sheet of stainless steel awaits, laid horizontal on a steel girder. Hunt uses the marker to trace the cardboard piece onto the metal sheet, then signals for his other assistant to come and help. This assistant dons a welder’s mask and fires up a plasma torch. A shower of sparks flies and soon a stainless steel twin to the cardboard piece is born.

Hunt brings the newly cut steel crescent back over to the model and holds it up where he wants it to go. It’s not quite perfect. He bends it with a wrench, then holds it up to the piece again. Still not right. He pounds it with a hammer. For twenty minutes he makes dozens of tiny adjustments to the piece, looking for the perfect form. His assistants flow seamlessly with his every move, anticipating his vision thanks to many years in his company. Hunt grabs a pry bar, a screwdriver, an arc welder, and then it’s a quick trip to the anvil; more bending, more hammering, more prying, more welding. Finally, Hunt smiles, holding the piece perfectly in place with a wrench. He glances to his assistant, who darts in and welds it firmly there. A few more smacks with a hammer and another twist with the wrench and Hunt is satisfied.

“Seal up all the little holes,” he tells his assistant. Sparks fly as he says to me, “Come on back over here.”

He grabs the second scale model, with which he is satisfied, and leads me back to the architectural rendering of the art center. He sets the model down on the rendering next to a stainless steel cut-out of the word KRASL. Hunt examines the layout of the area and tells me how these pieces are loosely based on another work he did long ago, but they are simpler, or, he says, maybe more direct. He’s not sure if that is the right word. It seems he has been trying for a long time to convey something humanistic, natural, and essential.

His assistant walks over and sets the freshly welded model, with its new feature, beside its companion. Hunt arranges them into the perfect configuration so that their branches are nearly touching. He then tells me about the feeling he hopes people will have when they pass beneath them. It has to do with optimism, creativity, and energy.

I ask how much of his process is physical — having to do with materials — and how much is metaphysical, having to do with existential moments like this one, when he finds himself contemplating what meaning his work might have to the people who encounter it.

“It’s always both,” he tells me.

He says the forms he creates in part come about because of the realities of the materials, like bronze or steel. But they also in part come about because of the sense of beauty that he’s trying to express. He doesn’t see them as natural forms exactly, but he says “they express natural tendencies,” like a gesture, a movement, or a process. Their humanity has something to do with the physical way Hunt has of interacting with them while fashioning their every element with his own body. Hunt hits them with fire, slices into them, bends them, and pounds on them with a hammer atop an anvil until eventually their lines become graceful and soft. His dynamism becomes the dynamism in the work. Every flaw is nurtured until it becomes beautiful; each separate element is coaxed into becoming part of the unified whole.

Richard Hunt’s dual sculptures, tentatively titled Wavelengths, will be unveiled at the grand re-opening of the Krasl Art Center in St. Joseph, Michigan, in October 2018.

Phillip Barcio is an American fiction author and art writer. His work appears regularly in Hyperallergic, IdeelArt, and New Art Examiner. His essay about the painter Young-Il Ahn is forthcoming in Western Humanities Review. His fiction has appeared in Space Squid and Swamp Ape Review, and his short story “What Is Let Go” won honorable mention in Glimmer Train’s Jan/Feb 2018 Short Story Award for New Writers contest. He lives and works in Illinois. Find out more at philbarcio.com.

Phillip Barcio is an American fiction author and art writer. His work appears regularly in Hyperallergic, IdeelArt, and New Art Examiner. His essay about the painter Young-Il Ahn is forthcoming in Western Humanities Review. His fiction has appeared in Space Squid and Swamp Ape Review, and his short story “What Is Let Go” won honorable mention in Glimmer Train’s Jan/Feb 2018 Short Story Award for New Writers contest. He lives and works in Illinois. Find out more at philbarcio.com.