One of my favorite magazines is a British publication called The Simple Things. Its mission is to inspire readers to live their lives fully by choosing fresh over processed, by going outdoors instead of staying inside, and by embracing both the practical and the playful. The magazine encourages mindfulness, curiosity, and wonder. Cook, they say. Read, they say. Consume as much tea and cake as you possibly can, and note all the small details around you.

When I came across Roanna Wells’s artwork in The Simple Things’ sister magazine, Oh Comely, I was haunted by her marked images, and knew I wanted to find out what her “simple things” were. It’s easy now to follow the artists we admire on Instagram or Twitter, and Wells’s social media is a kaleidoscopic collection of textures, shadows, and luscious swirls of combined pigments. Her work may have an eye-pleasingly clean and orderly aesthetic, but even simple things contain multitudes.

Wells is a fine artist who lives and works in the South Yorkshire city of Sheffield, England. She attended the Manchester School of Art, where she graduated with a degree in Embroidery. Her projects are about “quiet order, subtle structure, and collected detail which is offset by a curiosity into the spontaneous and accidental marks or residues of nature, human interaction, and the hand made process.” She has exhibited her work around the British Isles in addition to being featured on the Tate Britain’s Instagram as part of a takeover. Her next exhibit will run from June to December 2018 at Construction House, S1 Artspace, in Sheffield.

I’m especially interested in how visual artists make meaning and language out of marks on a page. We writers use words to do this, curving juicy strands of ballpoint ink into letters that we’ve learned over time to interpret as images, sounds, or emotions. But what happens when artists manipulate those curves and return them to their organic shapes, back into rows of carefully plotted and repeated pigment? How do artists tend this garden of meticulous pattern, and what is the narrative of a handwritten marked language when the letters have been bent back to their original lines?

I corresponded with Roanna about her obsessions, discoveries, and the healing benefits of a repetitive practice.

Where is your current studio? Can you describe the light and the sounds in the room? What can you see out your window?

I’ve had several studio spaces over the last year, as our organization, S1 Artspace, is currently in the middle of a transition to a new building. The spaces have always been situated in the city center of Sheffield: the first in a converted warehouse and the most recent situated in a huge Brutalist post-industrial building and the largest listed development in Europe — quite a place to have a studio! Our setup is an open plan layout, so we each have our own space, but within a community of other fine artists.

The studios are on a hill overlooking the city although the new space is going to be a converted garage block and will in fact have roof/skylights instead of normal side windows — the first time I’ve not had a window next to my desk so I’ll have to see how that goes — I love having a view, but maybe it’ll be less distracting not being able to see out!

I can hear a lot of the goings-on of the city, and am right near the train station, so I feel very connected even though I’m not directly in the city center. I enjoy the feeling of not being completely shut off from the world or other artists.

When and how did you begin integrating mark making into your art? Were you practicing other mediums before this?

At university, I was introduced to many different techniques and machines, but it was always the aspects of mark making and hand stitched / drawn / painted processes that grabbed my attention both visually and conceptually. Although my work has changed with different mediums, I have realized that the basis of most projects that use mark making are really about collecting — collecting data, people, lines, remnants. I love to sort and organize, and ever since I was small, I have always been drawn towards picking up tiny pebbles on the beach or shiny objects, or stripy feathers. There’s something about multiples and their relation to the individual that inspires a lot of my work.

What draws you to the shape of a mark, a smudge, a brushstroke? What worlds does a mark on the wall, or should I say, can a mark on the wall contain?

It’s hard to say what particularly draws us to certain marks or shapes. I suppose out of experimenting, trial and error, or practice, particular ones just seem to take a hold and become favorites. I’ve always ended up using very simple marks for repetition, nothing too complicated or pictoral. I find the simplicity of the shape allows for the attention to be focused on the effect of the repetition or mass accumulation of these marks, rather than the mark itself. [Interviewer’s note: See a video of Roanna in action.]

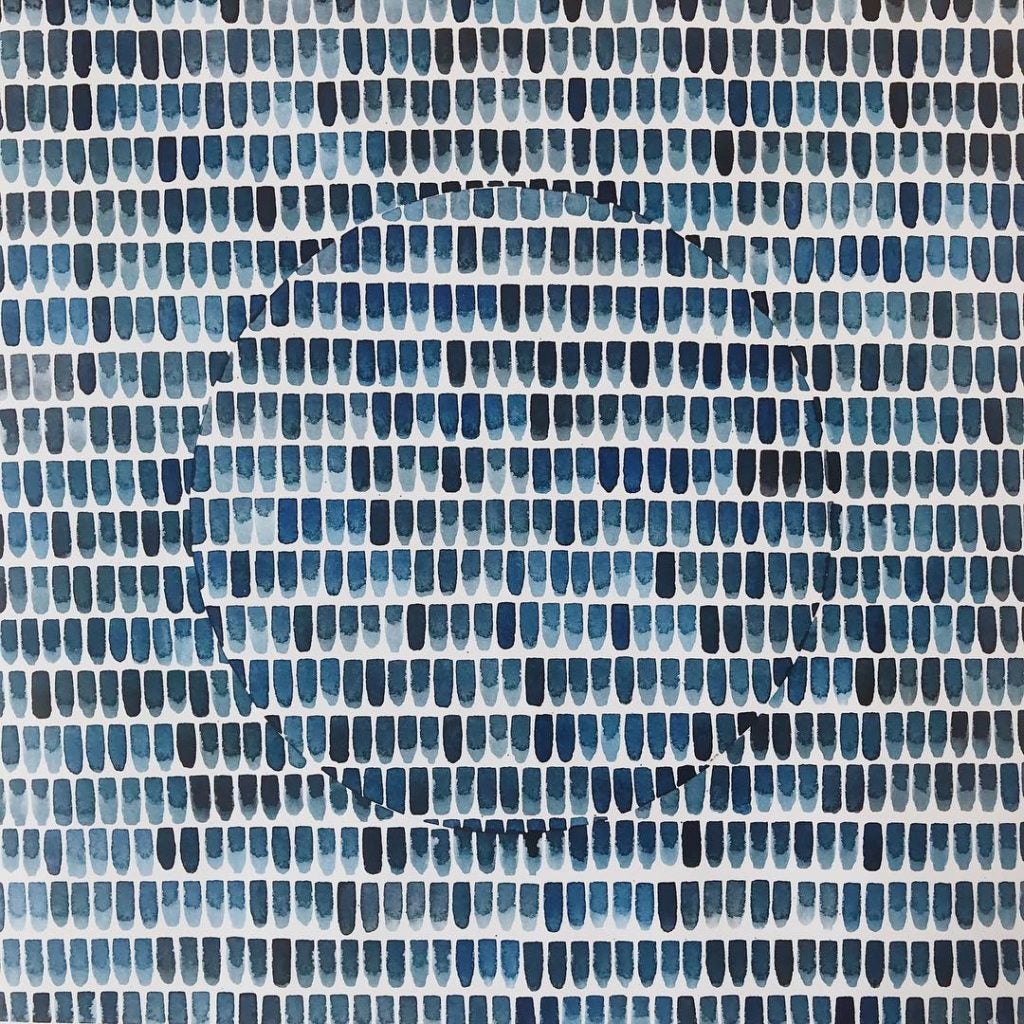

However, with the painted brushmarks, I also love how much variation can be found in each individual shape, even when only one size brush is used over and over. How gravity affects the paint differently depending on if it’s painted at the wall or on a desk, due to the way the watercolor pools and dries according to how diluted the paint is, or how two or more colors combine and blend. Pictures or little landscapes begin to form within each mark as well as within a group of marks together.

Do you see these marks telling a specific story? If so, what are the different elements to that story and how do they combine to give meaning to both the artist’s and viewer’s experience?

I love the act of repetition. Maybe it feels like a meditation of sorts, but I’m also interested in simplifying a technique down to a single mark or color, so as to allow space for the viewer to interpret the feeling, or to let a concept emerge if that’s what is intended. It’s fantastic how many different interpretations can be read into the same piece, and this slight ambiguity is something that has always featured in my work. I like the work to have several levels of understanding and appreciation, depending how deeply the viewer wants to look at it.

Your last exhibit was called “Tracing Process,” which seems a bit like an homage to the idea that making art is an ongoing activity — a process of tracing and retracing and creating new steps. Could you explain your goal for the project? What were you hoping to discover and what did you end up creating?

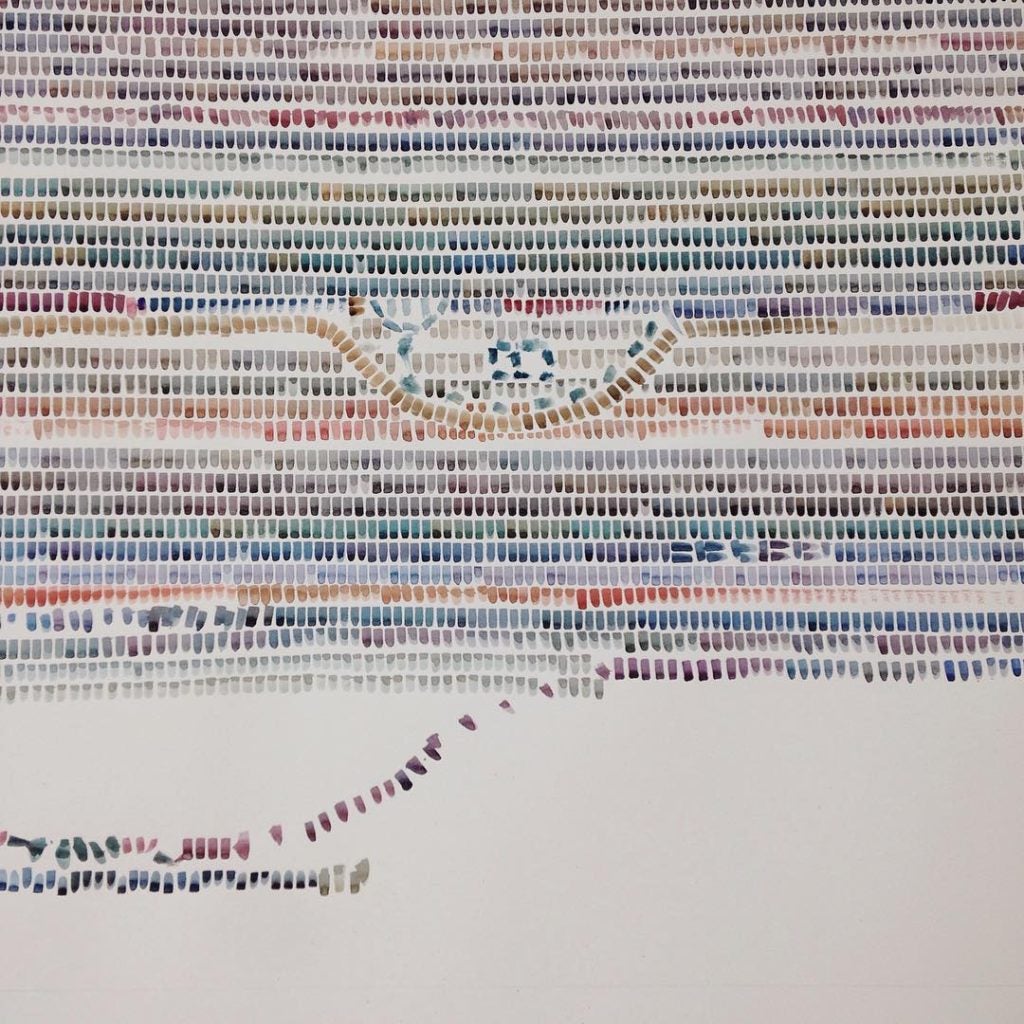

The aim of “Tracing Process” was both a self exploration and an opportunity to allow the public in to my work. I had started to become really interested in why my work was always so careful and neat, controlled, and structured. Maybe I was having a bit of a mini crisis, but I felt I needed to justify it somehow. I wanted to explore the way in which we all make marks differently and how they become our handwriting, or language. I wondered what would happen if I set up a space and began making a large painting in the way I would naturally work, but invite others to add their marks to the finished piece. It became a really beautiful dialogue between myself and anyone who wanted to contribute, which ended up involving over two-hundred people of all ages. I kept my marks even and the lines straight, working in and around the marks contributed by others, so that the contrast was clearly visible, even though they all eventually integrated into a whole.

In regards to your methodical visual work, how has it shaped the way you organize your day? Are you methodical in your daily life, too, or just in your art?

My studio days are probably not as structured as you might think at the moment, as I currently also work a second job (at my dad’s antique restoration business). So at the moment I just do what needs to be done when I get to the studio that week. However when I have a full studio week, I try to be more structured. I notice certain times of the day when different activities are most productive.

In daily life, I suppose I’m quite methodical. I like a routine but I try not to be too constrained by that. I do lots of extracurricular activities so I have a structure with those, and I do tend to have certain times of the day when I like to stop for a cup of tea!

Tell me about your favorite colors you’re drawn to use in your work. What do those colors remind you of? Do they hold specific memories tied to locations, people, or events from your past?

Tell me about your favorite colors you’re drawn to use in your work. What do those colors remind you of? Do they hold specific memories tied to locations, people, or events from your past?

I began using quite subtle combinations of colors, probably because it was a new departure for me after having used only monochrome for years with my stitched work. However, I have become more bold with color as I have progressed, and especially with the “Tracing Process” project where some participants chose to use the colors straight up without mixing or combining. This really encouraged me to strengthen my use of color. I’ve been investigating very bold tones for a possible experiment with digitally printed fabrics. On the other hand, I did a series inspired by Edmund de Waal’s ceramics, which are basically different shades of white and pale grey! I absolutely love Prussian Blue and when combined with Burnt Sienna, it makes the most beautiful turquoise-y tones. This spectrum of colors always reminds me of the deepest oceans, or the verdigris on copper.

In addition to the color turquoise, what are the ‘small things’ that bring you joy? What are your simple things?

My most favorite simple thing is the sound of the blackbird at dusk — especially at this time of year once winter is disappearing and spring starts to show — it makes everything OK. I love brushing my hair — not in a vain way, I just love the feeling of it. The sound of waves lapping on pebble beaches. Sand between your toes on the first day of a holiday. A good hug.

How do you know when you’ve reached the end of a project? As a writer, I find it difficult at times to know when to stop the story or when to continue the narrative. Do you feel this same conflict in completing a specific work?

Individual pieces are not so problematic, as often they’re finished when the paper is full of marks! However I do sometimes struggle with when to progress to new themes or develop something further, or to stop, leave something behind, and move on. It can feel easy to stick with what feels comfortable when you’ve developed a technique or concept that works, and can sometimes be daunting to branch out from this. However, it’s essential in order to keep moving on. Usually an idea for a new piece or theme will start to emerge during the creation of the current one or through discussion and conversation with others, and often it can just feel ‘the right time’ to try something else.

What/who are your artistic influences?

There are many artists who use contemporary drawing and processed-based techniques that I’m sure influenced my practice in a more direct way as I was studying and developing work. However, now that I feel confident to draw influence from my own understanding and concepts, I get most inspiration from artists whose work is visually very different to my own, in mediums that I love but have no particular desire to replicate. For instance land artists such as Andy Goldsworthy and Richard Long, light artists like James Turrell and Anthony McCall, sculptors like David Nash and Peter Randall Page, as well as ceramic artists such as Grayson Perry and Lucie Rie. There’s so much variety of artistic inspiration and I like to gather what I can from many different angles.

Images courtesy of Roanna Wells.