The piece of writing that (at this point in my life) has been most widely published and read is probably a poem I wrote as a high school sophomore. I went to a creative and performing arts magnet, and every year the writing department entered a contest dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy. The only requirements were that we write either creative nonfiction or poetry; that we focus our lens on race, religion, or gender; and (this may have been more implicit than explicit) that what we wrote be true. Three years in a row, I wrote poems about being Jewish. Three years in a row, I took first place for high school poetry.

That feels very uncomfortable to write. This whole post is uncomfortable to write. There’s the fact that I, a white girl with a lot of institutional and familial support, kept placing first in this particular contest; there’s the professional embarrassment of coming back to high school work, acknowledging that something I wrote fourteen years ago has been reprinted more than anything else I’ve written (this is not to discount how grateful I am–the contest is a tremendous opportunity for young writers); and there’s the fact that I am consistently unsure of whether I really have a right to call myself Jewish.

The question of what makes someone Jewish is very old, maybe as old as Judaism itself. Officially, Judaism is matrilineal. If your mother is Jewish, then technically, so are you. That isn’t something I knew until I was eleven, when one of one of my cousins informed me that I wasn’t Jewish because my mother isn’t. I bristled when my cousin said this. She was denying a big part of my identity, yes, but the statement also felt like an implicit accusation: it was my mother’s fault I wasn’t Jewish. Not being Jewish was something she’d done to me through negligence.

I don’t think my cousin was trying to hurt me. She clearly didn’t see this exchange as a big deal. She told me that I was not who I’d believed myself to be in a very matter-of-fact tone, as if she were telling me the tag was sticking out of my shirt collar. When I asked her why Judaism was passed through the mother, she shrugged and said, “You always know who a baby’s mother is.”

Is this really the reason? It seems plausible: The thing about Jewish law is, it can be brutally practical. If your people are historically nomadic and persecuted, the women always under threat of rape, doesn’t it make sense to say that any baby born to a Jewish woman is also Jewish? That way you’re unlikely to be wiped out. No matter how your child came to be, it is part of you, part of the community. But my mother isn’t part of the community so, by my cousin’s definition, neither am I.

According to my Catholic grandmother, however, I am. My non-Jewish grandmother was the first person to tell me that Jews are a race of people. If my father was of the Jewish race, then so was I. I reacted to this information with deep skepticism. It was 1998, and I had grown up in a mostly white, liberal community. Which is to say, I had been conditioned never to talk about race. Her suggestion that my father and I were a different race than she struck me as implausible (my whiteness felt pretty unambiguous); the fact that we were talking about race at all seemed rude and possibly offensive.

The thing about identity is, people are always trying to define who you are for you, to tell you what you mean. And we should be interrogating our positions in society, our privilege relative to our oppression, but we should also be skeptical of those who insist we are definitively one thing or another. As a kid, I felt confused and alienated by other people’s definitions of who I was. I wanted to be the one deciding. I didn’t fully understand that this is never really possible.

So I tried to write my way into being Jewish. Whether that worked is an open question.

~

I think I should explain my family here. My mother grew up alternating between Catholicism and Protestantism, her own mother changing her mind every few years. My mother’s faith is real but not limited to any particular category. My father and most of his immediate family are extremely, almost aggressively, secular. I have no idea whether he believes in God and have never asked.

I grew up celebrating Christmas and sometimes Easter. The only Jewish holidays we observed were Passover and Chanukah, and in both cases our celebrations were fun but completely half-assed (I didn’t even know you weren’t supposed to eat leavening during Passover until high school). My entire sense of what it means to be Jewish comes from those twenty minute Seders where we mixed up the blessings for the bread and the wine. Also: children’s books about the Holocaust. I read those books obsessively, trying to understand a history my family both claimed and avoided speaking about because our ancestors escaped Europe a generation before Hitler came to power.

The Holocaust. This mass murder that has come to define what it means to be Jewish in the twenty-first century. (When my partner, who also works in education, informed one of his middle school students that he was Jewish, she said, wonderingly, not entirely unimpressed, “Does that mean you would have died in a concentration camp?”)

I said no one in my family died in the Holocaust, but that could be wrong. My great-grandfather was apparently fast and loose with our family history, so maybe some of his siblings did get left behind in Europe. If they did, there is a strong chance they and their children were killed. His lies—I won’t get into them here, that’s another essay—endured for almost two generations before my family began to unravel them, and we still don’t really know what’s true. To be American, to be a Jew in America, changing your name, inventing your history, inventing your own Judaism, is to be a storyteller. You decide who you are. Or you try to.

~

When I tell my high school students that I am Jewish, they are always shocked. This almost never comes up, except in the context of the Martin Luther King, Jr. writing contest, which the school still participates in. Often, students ask me if I ever entered. I tell them yes. Did I win? Three times. But what did you write about?

They expect me to say, “Being a woman.” Their surprise at my Jewishness is always loud, excited, and mildly incredulous. Maybe it’s because there don’t seem to be a lot of Jewish people in the creative writing department. Maybe it’s because I don’t “look Jewish.” A friend once asked me how one can look Jewish and I told her the stereotype was dark, curly hair, big nose, short. Like all stereotypes, this idea is reductive and inaccurate, and like all stereotypes, it has a sticky staying power. We expect what we’ve been told to expect, even in the face of evidence to the contrary. I’m not tall or blond or button-nosed, but I look pretty WASPy. I look like my mom.

My students’ shock is always vaguely satisfying. It’s satisfying to confound someone’s expectations, to be a surprise. But below that feeling is unease: why does being able to pass as a gentile satisfy me? Conversely, why am I always so happy—and then so nervous—when another Jewish person immediately recognizes me as a fellow Chosen One?

~

Being Jewish in the way I am Jewish is to be both inside and outside of an identity. I never feel less Jewish than when I am in a gathering of other Jews, especially a small gathering, where my lack of basic knowledge makes me feel like a fraud. (My cousin isn’t the only Jewish person to implicitly or explicitly call my affiliation into question.) Conversely, I never feel more Jewish than when I’m surrounded by gentiles, which is another way of saying: I never feel more Jewish than when I’m afraid to tell someone I’m Jewish.

My relationship to my Jewishness is a little like my relationship to writing. Defensive, doubtful, loving. When I’m writing something, I’m also both in it and outside of it, building and being swept up in its current, not entirely in control. Writing is how I understand the world, fit life into framework, fit myself into a framework.

~

I called myself a “Chosen One” earlier, but I don’t actually believe that we Jews are more special than other people. I don’t believe we’re marked for tragedy or enlightenment. I don’t believe Israel is more my homeland than anyone else’s. But “chosen” is the right word in the sense that I chose Judaism. I chose it when I was in fifth grade, around the time I also decided I wanted to be a writer. And in a way, those life-defining choices stemmed from the same source: a children’s book called Time for Andrew. It’s about a twelve-year-old boy named Drew who goes back in time to save his great uncle, also named Andrew. They swap places, the uncle coming forward in time to the 90s, Drew going back to 1910. God, I loved that book! I wanted to write just like Mary Downing Hahn.

I was re-reading the book when my parents asked me whether I wanted to be Jewish or Christian. I think this was their way of settling the debate once and or all. Because Time for Andrew had made me obsessed with anything old, I asked them which religion was older. When they said Judaism, I decided that’s what I wanted to be.

Ever since that day, I’ve been telling myself a story. This is what I am, who I am. A writer. A Jewish girl. And if I can’t always sustain those stories, if at times they crack and I begin to feel like a faker, I can also come back to them in time, smooth over the weak parts, tell myself that only I decide who and what I am.

I often feel like a character in my own life. I’m trying to figure out who that character is, what she means, why it matters that she’s drawn to things old and complicated and beyond any one person’s understanding, things that can never fully belong to her. How can we love something so abstract as art? As God? But we do. We do. They shape our lives, these entities so frighteningly fragile that they might exist only as long as we believe in them, these forces we can hardly name and never truly define.

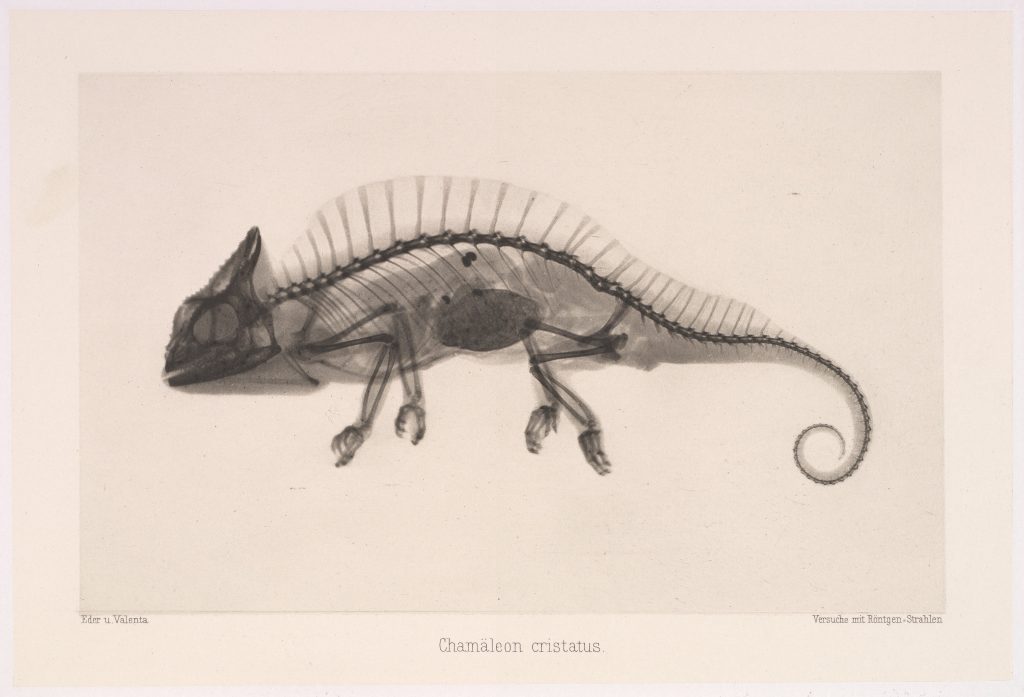

Image: Eder, Josef Maria. “Chamäleon cristatus.” 1896. Photogravure. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.