I knew the name “Michael A. Ferro” long before I met the actual person. He commented on anything and everything literary-related online, we had mutual friends in the writing community, and it didn’t take long for me to realize that Michael is one of the best literary citizens out there today. He’s often active on social media, commenting, supporting, and sharing other people’s work and achievements. Last year, we finally met at a reading in Ann Arbor, and since then, he’s been recognized for an Honorable Mention for Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Writers, plus he’s received the Jim Cash Creative Writing Award for Fiction.

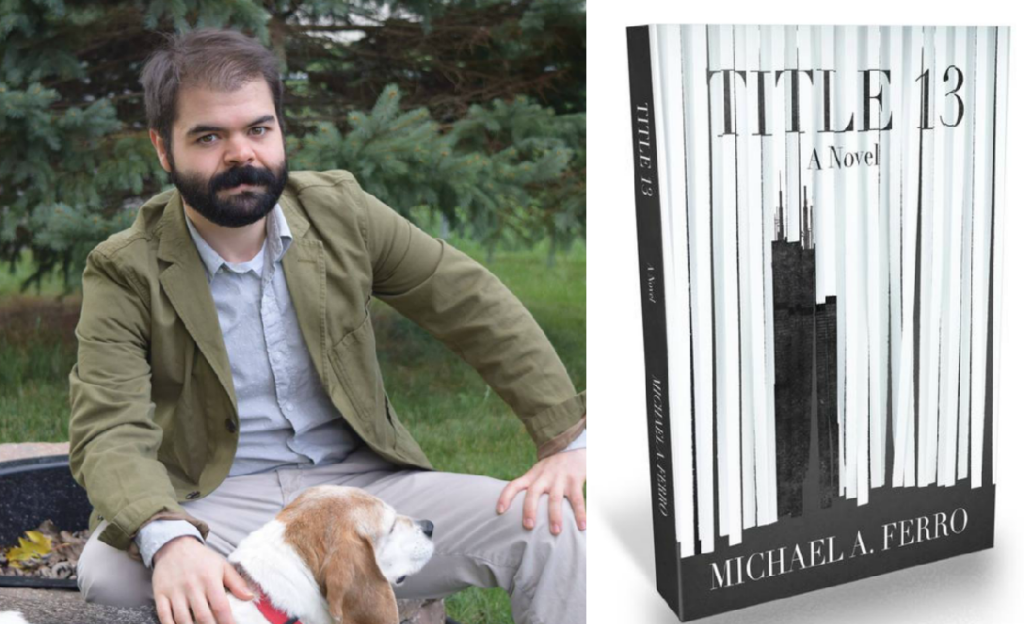

Ferro’s debut novel, TITLE 13, is out this month from Harvard Square Editions. I was thrilled to chat with him about the ins and outs of his grand Midwestern novel.

What was the first seedling for your debut book, TITLE 13? What was the crumb that grew into the five-hundred page novel?

I graduated from college back in May of 2008, right before the country began to comprehend just how devastating the economic collapse would be. Like any idiot, I hadn’t properly prepared for my post-college professional life and by the time I left school, companies were laying off employees left and right. It was a crushing time, especially here in the Detroit area where so many longtime auto workers were losing their jobs and young graduates couldn’t find work. I took a job tracking an invasive woodwasp for the State of Michigan (perfect for my Creative Writing degree, no?) and eventually got laid off from that.  On a weekend trip to Chicago — my first time there — I became enamored with the Windy City. It blew my mind. Young people were working, creativity was everywhere, and life felt like it was moving at an incredible pace — sadly unlike the way things were progressing back home in Detroit. Right then, like the proper idiot I was, I decided to take my savings and move to downtown Chicago without first securing a job. A few months later, as the very last of my savings dwindled, I finally found a job working for the federal government. That’s when things began to spiral out of control. Later, on one of my last days in Chicago, I wrote the first page of TITLE 13.

On a weekend trip to Chicago — my first time there — I became enamored with the Windy City. It blew my mind. Young people were working, creativity was everywhere, and life felt like it was moving at an incredible pace — sadly unlike the way things were progressing back home in Detroit. Right then, like the proper idiot I was, I decided to take my savings and move to downtown Chicago without first securing a job. A few months later, as the very last of my savings dwindled, I finally found a job working for the federal government. That’s when things began to spiral out of control. Later, on one of my last days in Chicago, I wrote the first page of TITLE 13.

Fast forward three years, I was back home living in Detroit trying to understand the world and what had happened. The awful Bush years were long gone and the country was finally heading in the right direction. We had hope with Obama and the promise of a new, more prosperous country ahead. And as I was embracing all of that, I couldn’t help but feel like there was some nefarious sub-element seething at the bottom of our culture — a toxic undergrowth that clung to everything pure and clean. Between trying to make sense of my own path after college, and that of this perverse component poking at the soft underbelly of America in the form of nascent Trumpism, I went back to that one page I’d written years before and began working on TITLE 13. I finished the book before Trump ever announced his campaign, but never in my wildest dreams did I think that the satire of my work would one day come to feel like real life, but it has.

How did you choose Heald Brown, a sort of everyman, as your protagonist? How might the story be different if we followed Heald’s coworkers, Milosz or Janice, instead?

Heald definitely draws his strengths from me, but more importantly, his weaknesses, too. TITLE 13 is filled with all sorts of hodgepodge characters, from the zany and bizarre, to the well-grounded and sensitive, and I wanted Heald to be able to identify with all of these elements as a singular character. Like so many of us, he’s highly emotional and feels so strongly about many of the things dividing our society, but he’s also a bit of an absurdist, which I think more and more Americans are being pushed into as a reaction to Trump and our volatile modern times. When you wake up and turn on the news and see something so asinine happening almost every hour, it’s hard not to lose your mind a bit. But through it all, deep down, you’re still that sensitive person who is trying your damnedest to make sense of things. That’s the essence of Heald—he’s coping, but he’s teetering on an edge.

Milosz represents the purity of America; the hardworking immigrant who is unjustly ridiculed and scapegoated. At the same time, he’s also innocent of so much of the evil happening in our country. If the story had followed his perspective, I believe it would be a flat-out horror story. Janice is Heald’s co-worker and, not surprisingly, the voice of reason and logic in TITLE 13. I knew as I was writing the book that if anyone was going to be a strong example for lucidity, it had to be a woman, because so many men have just lost their damn minds. If TITLE 13 were told from Janice’s perspective, witnessing all this absurdity and satire, it would just be too depressing.

Heald’s narrative often drifts off into long philosophical meditations. He thinks a lot about the way the world works and why. He doesn’t want to get trapped in a consumerist bubble. And yet, as the novel progresses, Heald Brown’s addiction to alcohol spirals him deeper and deeper into a hellish, inescapable bubble of his own making. Was it difficult to make your character suffer? Did Heald’s alcoholism open up any unexpected narrative seams for you?

It wasn’t difficult to make Heald suffer because when writing, authors usually pour their own suffering into their characters. It’s a sensation akin to setting down a heavy load, a sense of relief, at least for me. I feel physically exhausted after writing.  It’s often very therapeutic, a chance to exorcise demons, and if there is a universal human condition, it’s suffering, so while I may be torturing the reader a bit, I am also attempting to connect with them on a symbiotic emotional level.

It’s often very therapeutic, a chance to exorcise demons, and if there is a universal human condition, it’s suffering, so while I may be torturing the reader a bit, I am also attempting to connect with them on a symbiotic emotional level.

Heald’s alcoholism and mental illness is central to his character and his critical thinking. It often clouds his judgement and forces him to take a hard look at the foundation of his nature. In that way, his illness becomes relatable. We as readers all suffer from various forms and degrees of impairments and mental ailments that interfere with our connection to self-understanding, as well as complicate our social reasoning. When telling a story, I feel like it is important to try to crack the surface of our insular American experience in as many places as possible, then pour my characters into those seams like an epoxy.

Your skill with imagery and description is stunning. Every other sentence reads like a keen ethnographer’s journal of industrial city life — they are jotted observations on the strangeness of people and objects, as if we’re seeing them for the first time. I’m going to list a few favorites:

…puffing out her lower jaw like an anglerfish

His chest jutted out like misshapen papier-mache

The shallow cracks that he saw in the paint like wrinkles on aged skin had always been there

Little ranges thrust upward between two tectonic plates of paint

[Her eyes were] the colors of the earth—thousands of miles in two tiny spheres.

What is your process for seeing ordinary objects through your own unique perspective?

That’s so kind of you to say. I think, like a lot of writers, I see certain objects in everyday life and there’s a tangled connection in my brain somewhere that happens to associate two or more seemingly unrelated things that will sometimes yield a little literary nugget. They say that Ringo Starr came up with the malapropisms “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Eight Days a Week” and my guess is it’s something similar to that — seeing one thing in front of you and imagining another similar thing in your head and somehow making that connection to write an image as such. Sometimes these comparisons come easily (that’s when you really have to scrutinize them) and other times they come with great difficulty.

We are invited to listen in on the private meetings with Deputy Director Elina Flohard as she interrogates each office worker about the missing pages of the TITLE 13 document. These chapters are written in a typewritten transcript format. Do you have a background with writing screenplays? Why did you choose to play with form for these particular sections and what do you think the format adds to the tension of the story?

I took a few screenwriting courses in college as part of my Creative Writing degree and in that time produced one screenplay. I hope to never find it buried on my computer somewhere, because oh boy, it was ridiculous. As to playing with the form here throughout TITLE 13, I wanted to intersperse the manuscript with a few instances of typewritten transcripts just to heighten the tension and add another element of mystery for the reader. Who is writing these transcripts? How are they listening in to the deputy director’s private conversations? Is either character aware they are being recorded, and why? So much of the story in my novel is molded around the notion that “something isn’t right here” — that there’s always something happening to us, perhaps even on a cosmic scale, that we are unaware of—and it’s not only the characters who have to reconcile that fact, but the reader to some extent, as well.

In Chapter 7, Heald begins to tell his coworkers a horrific story he heard on the news earlier that day. In it, a window has detached from the Sears Tower and crushed a young mother. Once Heald begins to tell it, he finds he cannot stop, despite terrifying himself and his audience. Why does Heald feel compelled to tell these stories? Of more interest, what compels you to write stories?

Personally, I’m a glutton for punishment; it’s why I keep the news on in my house around the clock. Deep down, I’m terrified, but cannot look away. It’s almost like if I’m not plugged into what’s happening, I’m imagining things being much worse. Then I turn on the TV and see the latest headline and think, “Nope, this is much worse.”

I used to exclusively listen to NPR on the radio for my news, as well as supplement it with the New York Times and The New Yorker and whatnot, but with Trump, everything is sensationalized. It’s addicting in the worst way possible. You think crack addicts continue doing crack because they like it? It’s because they can’t help themselves, and that’s what we’ve stepped into with current news coverage. And I’m absolutely guilty of this, too. I’m transfixed and sick, like a fiend craving his fix. Even when it comes to the grisly and more horrific aspects of our lives, I’m that guy who’s staring right at it, hypnotized — I can’t look away. I’d prefer to see or hear about something horrendous, rather than let my mind imagine it. Of course, the mind then takes that horrible thing and twists it around, making it exponentially worse, so there’s no winning for people like me.

To that effect, I think what compels me to write stories is the simple act of getting them out of my head. In an effort to become better people, we’re always trying to make sense of our past or some trauma that we suffered through, and for many, we use art and creativity to do this. Musicians create songs, painters paint paintings, and writers write stories. But you don’t have to be an artist to work through some psychological impasse. In fact, many people achieve a clearer state of mind just by feeling more connected with the world. Whether it’s making art, reading a book, or just absorbing it through their daily activities. It’s all about relating yourself and your problems with the grand scheme of the universe, which certainly sounds highfalutin, but when staring up at the night sky alone on a moonless night, it kind of makes sense. Sometimes.

You are a true Midwesterner, born and bred in Detroit, just like Heald. TITLE 13, which chronicles a Midwestern experience following the 2008 Recession, joins a contemporary collection, along with Matt Bell’s Scrapper, of books documenting the Midwest’s turbulent role through the 20th and 21st century. This group of books doesn’t just tell stories. They are histories of the past and people of the Rust Belt. Why do you think stories of the Rust Belt and “the industrial Midwestern town” is an important contribution to today’s literary world?

I believe that the story of the Midwest is the story of America. As evidenced by the 2016 election, the Midwest is not a region to be trifled with, nor ignored. There are so many wonderful people here in this part of the country and each of them has a unique story to tell. The coasts certainly have their intellectual pillars of modern thought, but when it comes to true heart and grit, the Middle West is where it’s at. Detroit in particular has an idiosyncratic history that separates it from the rest of the Midwest; it’s almost as if Detroit is the “Midwest of the Midwest.” We’ve gone from such highs — being the fourth most-populated city in the country — to terrible lows. It was definitely a case of “the bigger they are, the harder they fall.” But because of that fall, and for so many other similar cities throughout the Rust Belt, Detroit and the Midwest is full of stories: great families crumbling, fortunes made and lost, individuals staking a claim in the heartland to capture their American dream, and so on. The Midwest is also accessible, unlike other parts of the country, so our stories are generally universal and relatable, and for that reason, essential to the modern American canon.

The phrase “Memento Mori” (Remember Death) is written on the back of a photo of Heald’s childhood dog. In Chapter 26, you write a beautiful meditation on the unconditional love of a pet. Humans know that we will eventually die. However, “a dog could only embrace love absolutely, without hesitation, and could devote itself to it with complete and unabashed abandon, for the world was forever.” This reminded me of one of my favorite Dutch poems: “Spleen” by Michel van der Plas. It has a line: “I wish that I were two dogs / then I could play together.” This poem, to me, is the epitome of love and creativity, free of the doubt, stress, worries and preoccupations humans muddy their lives with. Do you think that it is a benefit or a disadvantage to be so concerned with death? What do we lose by not being present in the moment, by not being more “dog-like”?

First off, thanks for the very kind words! I’d not heard of Michel van der Plas before, but that’s a wonderful line. Ah yes, death — that one thing that no human can truly ignore. One of the great struggles of my life, and I’m sure it’s the same for many others, is wondering whether or not it’s a good thing that we possess the questionable gift of knowing we will die. At times, I think it’s a benefit, because it allows us to truly value the time we spend above ground, but then again, I look at my dog and he certainly doesn’t seem to value his time any less despite being unaware of death. And then there’s the whole notion to the responsibility of utilizing that value in life knowing that it is temporary, to not squander it, and by the very same turn feeling guilty and depressed whenever we do. It can make for some wonderful reading and long, fruitful conversations of waxing philosophic, but it’s also incredibly taxing on the mind and ends up feeling like a burden to some extent.

Then you sit back for a moment and realize you’ve done all this thinking about death and the ramifications of contemplating it and all the meanwhile your dog is out running around the park chasing a bird, playing with other dogs, and smelling every nook and crotch and cranny of every single thing without a care in the world other than love and companionship and you can’t help but feel envious. Then you begin to second-guess everything you’ve done in your life up to that point.

What’s next for you?

Up next is the book tour and publicity events, but immediately after that I’ve scheduled a month of sleep. Once that is over, I plan to begin work on my next novel, which I’m thinking will focus on a post-Trump Midwest. In addition, I’ll also continue writing short stories, as well as humor and satire pieces, because those are the things that truly keep me going between big projects like a novel.