If you are reading this review out loud, untie a silky ribbon from around a bouquet of flowers. Rub your thumb against it. Use the ribbon to reattach your head to your neck. You’ll need it for this particular task of reading. Secure with a tight bow. Do not doubt the double knot.

In Her Body and Other Parties (Graywolf Press, 2017), Carmen Maria Machado explores the bodies, demons, and desires of twenty-first century women. Featuring a woman who can hear the thoughts of actors in porn videos, an unapologetic list of sexual partners amidst a national influenza epidemic, a woman who realizes ghost women are sewn into the seams of haute-couture dresses, and a woman haunted by the flesh she lost in a gastric bypass, the debut collection creates an honest space for unforgettable women to speak out about the devastating need for human connection; of the hunger which rips at our throats, pulses in our loins, and growls madly through our minds.

Shortlisted for the 2017 National Book Award, the collection is held together by themes of desire, horror, and grief. The book begins with “The Husband Stitch,” a haunting retelling of the age-old campfire story of the girl with the green ribbon wound around her neck. In her modern-day adaptation, Machado reflects on the history of ghost stories and urban legends. “Everyone knows these stories,” the narrator says, “that is–everyone tells them, even if they don’t know them—but no one ever believes them.”

The green ribbon weaves the book together by binding tales told by similar protagonists: women simultaneously transparent and secretive. They have beautiful, bold bodies; they are full of contradictions; they come in all shapes, sexual orientations, and sizes; they are hetero, queer, sexually hungry, strong. They are fragile, fat, outspoken, curious. They are doubtful, omniscient, and elusive. Frankly, Machado writes about women who are real.

If you are reading this review out loud, stand before a mirror. Watch the mirror quake under the force of your voice. Is it you who looks back at yourself? Your eyes, my how they’ve changed.

An impressive centerpiece to the collection is the novella “Especially Heinous,” a story inspired by Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. Using the real titles of episodes from the first twelve seasons, Machado writes an alternative storyline for Detectives Benson and Stabler. Each “episode” reads as a plot summary one might find on Wikipedia or Netflix, and gives just enough information to tease our imaginations and awaken our nightmares. In true Machado style, the uncanny and fantastically horrific lurk around every corner.

For example, from Season 7 come the episodes STRAIN and RAW:

“STRAIN:” Benson gets the flu. She vomits up: spinach, paint shavings, half a golf pencil, and a single bell of her pinky nail.

“RAW”: Benson and Stabler’s favorite sushi restaurant has stopped using plates and started using models. Benson pinches a red swatch of tuna from the hip bone of a brunette who seems to be trying very hard to not breathe. The owner stops by the table, and seeing Benson’s frown, says, “It’s more cost-effective.” Stabler reaches for a piece of eel, and the model takes a sudden breath. The meat eludes his chopsticks—once, twice.

As the “show” goes on, the episodes become more superbly strange. Benson and Stabler are pursued by shadowy doppelgängers called Henson and Abler; Benson is haunted by a flock of girls-with-bells-for-eyes, and women and children continue to be killed. The amazing thing, perhaps, is that at the end I didn’t find myself asking what was up with the girls-with-bells-for-eyes; instead, I asked myself how a TV show that hinges on violence toward women has risen to such fame. How is such fictional entertainment any different than watching the actual news, and by watching these shows, are we prolonging or solving the very real problem that is sexual assault? “Especially Heinous” in particular is where Machado shows her chops as an experimental writer, and proves to the literary world that narrative energy can also be formally daring.

If you are reading this review out loud, spit out your words. You’ll hear the sound of coins jangling against hard porcelain. Notice the color that comes out of your mouth and log the exact shade in your notebook. Repeat at the same time tomorrow. Then, carry on with reading.

In “The Resident,” a novelist travels to a rural artists’ colony eerily close to the site of a mysterious trauma from childhood. Among the narrator’s concerns is that her experience will be reduced to a trope: “Perhaps,” she says, “you’re thinking that I’m a cliché—a weak, trembling thing with a silly root of adolescent trauma, straight out of a gothic novel.” The story continues to investigate the troubling act of stereotyping women as mad, both in literature and life:

Lydia filled my glass to the brim. “Do you ever worry, “ she asked me, “that you’re the madwoman in the attic?” “What?” I said. “Do you ever worry about writing the madwoman-in-the-attic story?” “I’m afraid I don’t know what you mean.” “You know. That old trope. Writing a story where the female protagonist is utterly batty. It’s sort of tiresome and regressive and, well, done”—here she gesticulated so forcefully that a few drops of red spattered the tablecloth—“don’t you think? And the mad lesbian, isn’t that a stereotype as well? Do you ever wonder about that?”

When the narrator explains that her novel’s protagonist is a version of herself, Lydia responds, “So don’t write about yourself.” “Men are permitted to write concealed autobiography,” the narrator responds, “but I cannot do the same?” Later in the story, she etches her name into her writing desk, as the residency’s previous guests have done: “C—— M——.” The same exact initials for Carmen Machado, the writer of “The Resident.” This not-so-subtle wink screams, ‘If you can’t join them, beat them,’ and in this story, Machado beats stereotypes to the ground by charging them head on.

If you are reading this review out loud, cover your neck with your throat. Speak and feel the vibrations. Be careful with the pressure of your fingers. Squeezing too hard may have fatal consequences.

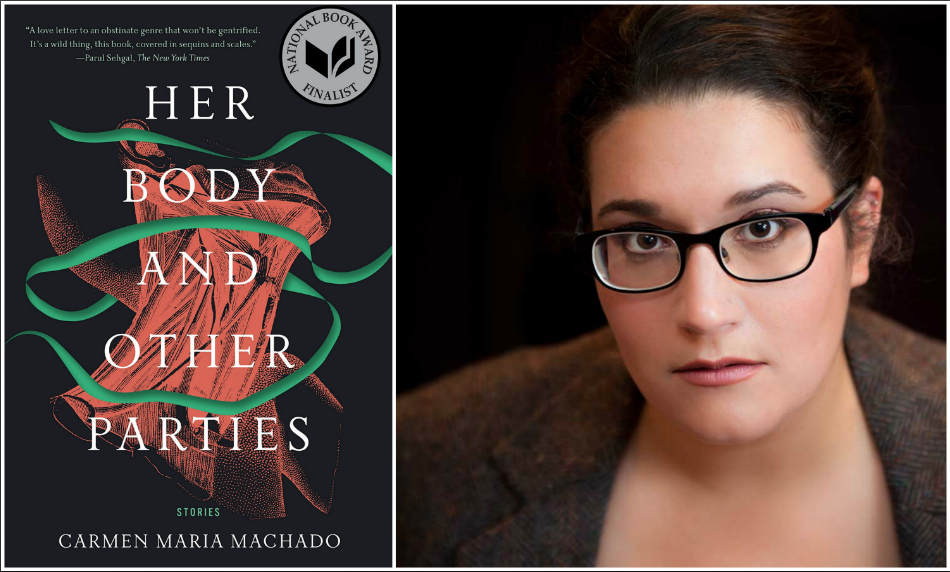

I find myself more and more intrigued by the production of book covers, particularly the ones coming out of smaller independent presses. It wasn’t until reading this interview with Machado and her book designer, Kimberly Glyder, that I realized I had been looking at the cover all wrong. (Or not wrong, per sé, but I’d missed the intended mark.) What I’d seen as a cinched red corset wound delicately with a green ribbon turned out to be an old medical illustration of a woman’s lower jaw and neck musculature. Like one of those 3D illusion pictures, depending on how you choose to focus your eyes, the green ribbon is either in the process of tying or untying—a powerful symbol in itself. I admit that now that the secret of the muscled neck has been unveiled to me, I cannot unsee it.

I find myself more and more intrigued by the production of book covers, particularly the ones coming out of smaller independent presses. It wasn’t until reading this interview with Machado and her book designer, Kimberly Glyder, that I realized I had been looking at the cover all wrong. (Or not wrong, per sé, but I’d missed the intended mark.) What I’d seen as a cinched red corset wound delicately with a green ribbon turned out to be an old medical illustration of a woman’s lower jaw and neck musculature. Like one of those 3D illusion pictures, depending on how you choose to focus your eyes, the green ribbon is either in the process of tying or untying—a powerful symbol in itself. I admit that now that the secret of the muscled neck has been unveiled to me, I cannot unsee it.

And that, perhaps, is the most important lesson of Machado’s collection. It is chock-full of stories of women’s experiences and voices that often are not heard or seen. After reading Machado’s poetic imagery, horrific motifs, and haunting characters, that silence is shattered. All is visible. Not even shadows can escape. The book’s cover depicts the beauty and complexities of being a woman—especially a queer woman—investigated within Her Body and Other Parties.

If you are reading this review out loud, when you are finished go immediately to your local bookstore and say, “I would like to buy this book, please.” DO NOT UNTIE THE GREEN RIBBON AROUND YOUR NECK. At this time, you may stop to use the bathroom. While you’re in there, take a bloody finger and draw a self-portrait on the wall. Don’t initial it. Then, go straight to the coffee shop. Before you sit down to read “The Husband Stitch,” drag the chair across the wood floor. Feel your shoulders twitch at the sound of the squeak.