Nonfiction by Zhanna Slor excerpted from our Summer 2017 issue.

In 1933, the year of Stalin’s manufactured famine, almost seven million people in the Soviet Union starved to death, more than the number of Jews killed in the holocaust. My great-aunt Polina was two and a half at the time, and she hardly noticed the deficiency of food; what she did notice was the nearly constant lack of her parents. Her father jumped from job to job for years before removing himself entirely by remarrying another woman, having a baby. Her mother, despite never having finished third grade, had just been made head of manufacturing at a factory in downtown Kiev that created wool sweaters. When she wasn’t working, she spent hours at weekly komsomol meetings — the communist young-adult organization — where she was an important, high-ranking member. In those days, Jews made up only four percent of the party, and were not allowed to work in even the lowliest civil service jobs, so this was quite a feat. But it also meant Polina’s mother had to work three times as hard as a non-Jew, often leaving her daughter with neighbors or family members for days at a time. That winter, Polina had even gone an entire five weeks straight without seeing her mother who’d left with a communist brigade to a nearby village, where they were sent to confiscate all grain and surrender it to party officials.

Being alone became a part of Polina’s life. There was one day in particular that stuck in her mind. Her beloved uncle wasn’t around, so Polina’s mother had to leave Polina with the neighbors’ teenage daughters, who only agreed to do it in exchange for a week’s rations of bread. All day long Polina sat anxiously waiting in her neighbors’ apartment, with its cracked windowpanes and boiling sausages, filled wall to wall with beds, piles of clothing, and damp water buckets sweating into towels. The place was even more crowded than her own communal apartment, which housed not only her and her parents, but Polina’s uncle Ivan and his childless wife; her father’s sister Roza, a sweet woman who shared the living room couch with her husband; as well as a fat old lady who never spoke one kind word to her — and who, Polina would only find out after the lady’s death, was actually her grandmother.

For a while, it wasn’t so bad there. It was definitely worlds better than the nursery where she’d stayed for those long, hungry five weeks while her mother had been away confiscating grain. Where, every day, they lived on nothing but a few peas and stale bread, and children often disappeared forever, rolled out under white sheets. The women who ran the nursery, who she’d have nightmares about for the rest of her life, had treated Polina like she would likely drop dead at any moment too. Whenever they came to wheel away another body, they seemed surprised to see Polina open her eyes, as if they saw some weakness in her that Polina was not aware of. But Polina was not weak. She didn’t even mind so much the lack of food; all she would end up remembering from that time was that she felt she might die of loneliness. The thing she feared the most, more than those old women dropping a sheet over her body and wheeling her into the mortuary, more than never seeing another piece of good bread again, was that she would get left in that nursery for the rest of her life. Every day that no one came to pick her up, that fear grew exponentially. So that now, months after she’d returned from the nursery, every minute she stayed with her neighbors brought more worry into her poor, tiny heart.

By all accounts, she should have been enjoying herself. The girls in charge of watching her took turns holding her in their laps, even pinched her cheeks and pronounced she was darling. They pinned a ribbon to her curly black hair, rocked her in a rocking chair, which smelled faintly of industrial soap and old wood and almost drowned out the other strong odors of the house: sweat; wet, drying sheets; dirt and dust. They attached a safety pin to her skirt to ward off evil spells and sang her lullabies they remembered from their own youth. They were sisters, two years apart, best friends. Alla and Nelya, they were called. She’d seen them many times in the hallway, on their way to school in heavy wool uniforms and pointed white caps.

“I’m tired of these games,” Alla said, after they’d gone through the entire repertoire of songs they knew and it was still daylight, still no knock on the door.

“Let’s get out of here,” Nelya said.

To continue reading “Surrounded,” purchase MQR 56:3 for $7, or consider a one-year subscription for $25.

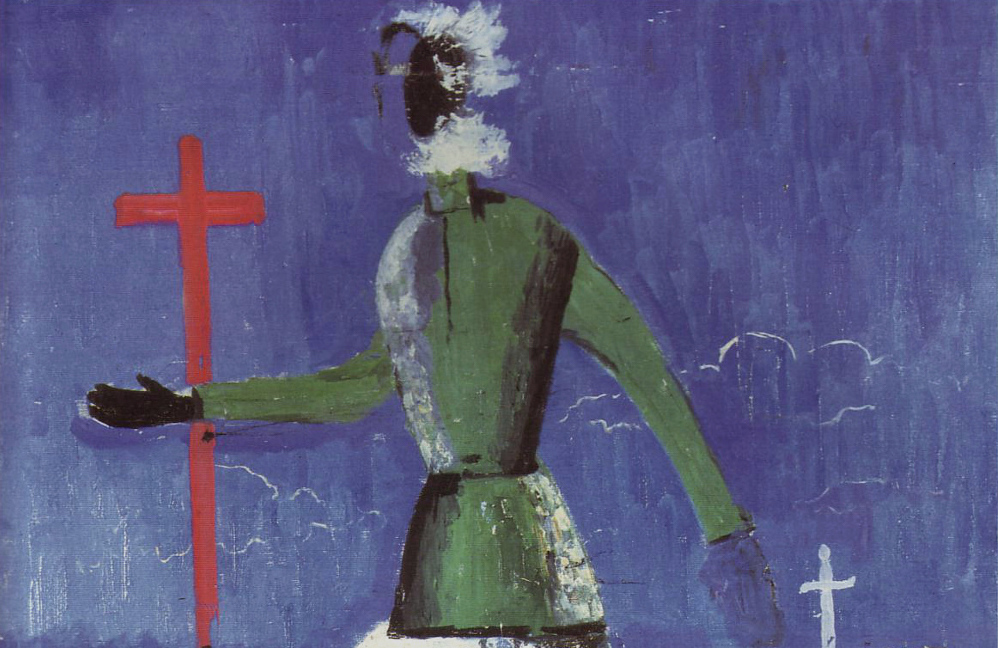

Image: Malevich, Kazimir. Detail of “The Running Man,” or “Peasant Between a Cross and a Sword.” Ca. 1932. Oil on canvas. Musee National d’Art Moderne, Paris.