I met Nguan, a photographer from Singapore, online; on Instagram specifically. I follow other artists on this platform when I admire their work, and Nguan’s pastel prominent images kept haunting me. Not only does his work have a distinct, consistent aesthetic, it also presents seemingly simple scenes which again and again I see as possessing complex, underlying narratives. Nothing is as simple as it appears.

Nguan attended Northwestern University, where he graduated with a degree in Film and Video Production. His photographs are about big city yearning, ordinary fantasies, and emotional globalism. He has exhibited his work around the world, and his photographs are in the permanent collection of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM).

Before I reached out to Nguan for an interview on the subject of his new book, Singapore, I kept reading online that he doesn’t often do interviews, and he never allows the camera to point towards him. The irony of this choice isn’t lost on a fan; Nguan has over a hundred thousand followers, and they haven’t been obtained by posting selfies or oversharing personal information. Instead, the simplicity of Nguan’s photographs is an extension of his personality. As someone who loves language, I appreciate that Nguan allows followers and admirers of his work to fill in the story beneath the surface of his photos. So I decided to take a chance and inquire as to whether he’d be interested in doing an interview for MQR. I’m so happy he agreed.

How did you begin in photography?

How did you begin in photography?

I got into it relatively late, after graduating from college. I’d considered being a writer or an illustrator, but I found both writing and drawing to be really arduous processes. I always ask writers: Is it difficult for you, too? Do you sweat and cry a lot when you write? On the other hand, photography feels like breathing to me. I was initially drawn to how the simple act of taking a picture could corroborate an experience in the absence of a companion or fellow witness, and I began by bringing a small camera with me on solitary walks in the city. As I became more cognizant of photography’s other uses, my walks grew longer and my cameras grew larger.

What is your process?

What is your process?

Taking photographs and editing a book are both about making choices. I’d go as far as to say that photography is primarily an act of editing. After all, there are a thousand different things outside on the street that could lay claim to my attention at any given second. As a photographer, it’s my job not only to show the viewer what’s pertinent to see, but also to organize that information and present it as succinctly as I can.

Singapore is a gorgeous book. Can you discuss how you came up with the concept?

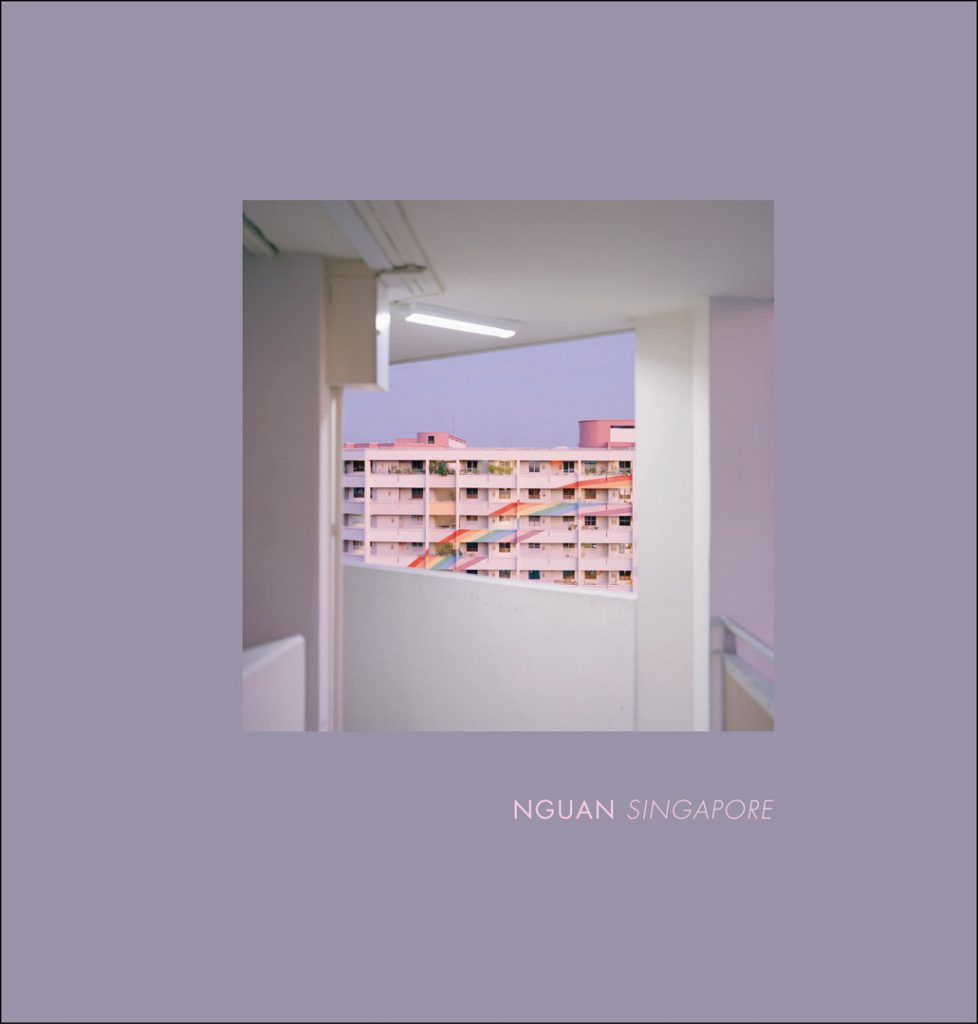

Singapore attempts to create a fantastical version of the country using purely documentary methods. The book collects candid portraits, landscapes and still lifes taken over the past ten years. I wanted to craft an original portrayal of the place that felt honest yet mythical and dreamlike but true.

I feel as if the photos are perfectly arranged; so many of them seem to be in conversation with one another — the man on a pay phone juxtaposed with a girl on a cell phone, a girl walking down a staircase and an empty staircase leading up to trains — can you discuss how you decide upon these pairings? Is it in your editing process that you discover these relationships?

Yes. I’ve always been intrigued by how images speak to each other and how the meaning of an image can mutate according to what’s adjacent to it. I paired images whenever I felt their union made them stronger. There is also a plethora of match cuts in the book, possibly as a consequence of my time in film school.

Having a decade’s worth of images to choose from made things easier as well as harder. I fiddled with editing until moments before I had to deliver the final document to the printer. I’d probably still be fiddling now if the book wasn’t already printed — it’s just the way I am.

What has your experience been living in Singapore?

What has your experience been living in Singapore?

The artistic environment is generally uninspiring, and there can be a poverty of imagination and taste. Quite often my head lives elsewhere. But the food is great, there’s magic in the back alleys, and it’s summer here all year round.

I notice a lot of soft colors; in my mind, this juxtaposes nicely with the harshness of the city; are you naturally drawn to softer, pastel colors?

That’s certainly the intended aesthetic of this work — I wanted to simulate the palette of coloured pencils. The book is meant to resemble an illustrated children’s fairy tale on its surface, with dissonant themes lurking below.

As a multidisciplinary artist, I appreciate the presence and absence of words, and often find that my mind compensates by creating a narrative alongside the images you include — for example, the series of chair photographs. Do you think in terms of narrative when you arranged Singapore?

I love that you’ve mentally filled in the blanks. On a related note, some of my favorite theater going experiences have been at semi-staged readings, where only bare sets and simple costumes are used. When an actor looks up at the sky and the audience looks up with him, the sky we’d have to imagine in a semi-staged production is infinitely more wondrous than a painted or projected sky might be in a fully staged production.

Several friends and journalists have noted the absence of text in Singapore. I have the most immense respect for the authority of words; that’s why I’ve not allowed any into the book. I wanted to let my pictures run free. I absolutely did have a narrative in mind while editing Singapore. I carefully justified the inclusion of every single photograph to myself; each one had to bring the “story” forward. But while I have a clear idea of what I mean to say, it isn’t necessary for the viewer to know it, or for us to imagine the same sky. I’d prefer it if you formed your own ideas and narratives, and perhaps we can meet somewhere unanticipated.

All photographs courtesy of Nguan.