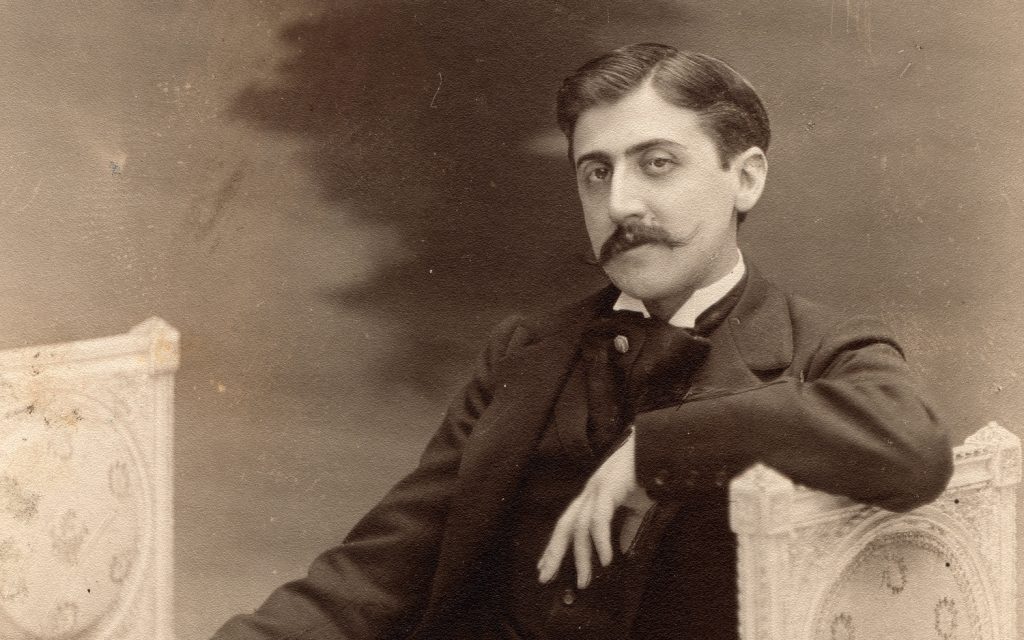

For Franz Kafka, the source of it all was children. It didn’t matter if the kids in his Prague neighborhood looked angelic. They all made the same hellish noise: “It drives me from my bed, out of the house in despair, with throbbing temples through field and forest, devoid of all hope like a night owl.” For Schopenhauer, who considered noise an impediment to clear thinking, it was the shrill sound of drivers whipping their horses: “The most inexcusable and disgraceful of all noises is the cracking of whips — a truly infernal thing when it is done in the narrow resounding streets of a town.” And Marcel Proust, a known sufferer of misophonia, lined his one-bedroom apartment at 102 Boulevard Hausmann with cork just to shut out noise.

Less well known until recently is how Proust delicately negotiated with, bartered and bribed his third-floor neighbor, Mme Marie Williams, to keep the racket down. Williams was the wife of an American dentist whose practice was in the same building. In 2013, Gallimard published a previously undiscovered collection of twenty-three letters addressed to Williams, dating back to 1908, which have been freshly and deftly translated for an English-speaking audience by Lydia Davis.

Less well known until recently is how Proust delicately negotiated with, bartered and bribed his third-floor neighbor, Mme Marie Williams, to keep the racket down. Williams was the wife of an American dentist whose practice was in the same building. In 2013, Gallimard published a previously undiscovered collection of twenty-three letters addressed to Williams, dating back to 1908, which have been freshly and deftly translated for an English-speaking audience by Lydia Davis.

The letters are remarkable in part because they are not sent to distant correspondents in far-flung countries or even in adjacent cities but to recipients within the very same building, almost always traveling to-and-fro between a few floors. The letters thus seem to function as a means of evading emotional confrontation with those nearby. While it is clear that Proust’s sensitivity to noise is what drove him to write the letters, his pleas are often buried deep in the subtext. In one letter to Williams that chronicles his illness, and consequently, his inability to receive André Gide, he inserts an observation into the postscript: “The successor to the valet de chambre makes noise and that doesn’t matter. But later he knocks with little tiny raps. And that is worse.”

Proust’s seemingly nonchalant complaint about the valet de chambre is actually a veiled request for silence from Williams herself, a circumlocution for which Proust’s writerly sensibility had well prepared him. Similarly, in another letter, he slips into talking about himself in the third person, distancing himself from the writer who absolutely must have some unperturbed time: “He would be most grateful to her if she would be his spokeswoman with the Doctor to request that there not be too much noise tomorrow.” Yet the oblique way with which these requests are inserted actually drives more attention to their imploring tone.

When the noise becomes too great for Proust to handle and he has to address the issue head on, we see the novelist literally calculating the cost of silence. He asks Williams to move the hours of her husband’s workers around and to bill him for the expense: “I absolutely expect you to tell me what I owe you for the expenses I occasion you by these shifts in the workers’ hours.” This bartering about what activities must be taken up at which hour extends to daily errands; a Proust aware that the dentist is leaving Paris and that his crates must be nailed, writes imploringly, “would it be possible either to nail the crates this evening, or else not to nail them tomorrow until starting at 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon.”

The courteous yet urgent tone of the letters prompts a series of exchanges and gifts that are meant to ease the discomfort caused by a neighbor who is far too aware of what his fellow apartment dwellers are up to. To thank his neighbors for inconveniencing them, Proust often sends Williams flowers, a common theme that runs through the letters. Although the rules of politesse at the time dictated that a man could only send flowers to a married woman through her husband, we often see Proust breaking this rule and sending roses directly to Williams, ostensibly to ease the frequency of his requests. What starts with roses soon devolves into more extravagant gifting: “my asthma attacks are too intense to procure me a little silence… I hope that you will be willing to accept these four pheasants with as much simplicity as I put into offering them to you as neighbor.” As with paying the workers, Proust’s gift of the gamebirds functions as an under-the-table currency of quiet.

Yet it would be too simplistic to view these letters as simply mercenary instruments of trade. Though we do not have access to Williams’s letters, it is clear that the pair also exchanged books. Proust alludes to Williams owning his Les plaisirs et les jours and sends instructions on how to approach and think about the various volumes of La Recherche (“the 2nd volume itself doesn’t mean much; it’s the 3rd that casts the light and illuminates the plans of the rest”). The missives also have literary merit. Eschewing punctuation, save for the wayward comma or the rare period, the letters mimic Proust’s flowing style and predilection for long sentences. In her afterword, Davis notes how she wanted to stay close to his stylistic choices in her translation, “not supplying missing punctuation or correcting mistakes, but at the same time trying to retain as much of its grace, beauty, sudden shifts of tone and subject, and distinctive character.”

As years go by and the first World War wreaks its havoc, the letters become more intimate, chronicling worry as well as the absences of friends. In one letter from 1914, Proust writes of going up before the military service review board as well as the death of his secretary Alfred Agostinelli, the putative inspiration behind the figure of Albertine, who fell from an airplane and drowned on May 20, 1914. The same year Proust informs Williams with frustration that due to the war, the second and third volumes of La Recherche cannot be published. In 1915, he writes that his friend Bertrand de Fénelon has been killed and, at the same time, conveys his condolences for the death of Williams’ brother. His letters become a curious mixture of sadness and flirtation in addition to the various subrosa demands for peace and quiet. The portrait these letters paint of an artist trying to hone his craft at all costs transforms them from obscure Proustiana into a richer portrait of Proust the man, neighbor, and writer.

Ayten Tartici is a writer and PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Yale University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Atlantic, MAKE Literary Magazine and Inventory Magazine. Follow her on Twitter @AytenTartici.

Ayten Tartici is a writer and PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Yale University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Atlantic, MAKE Literary Magazine and Inventory Magazine. Follow her on Twitter @AytenTartici.