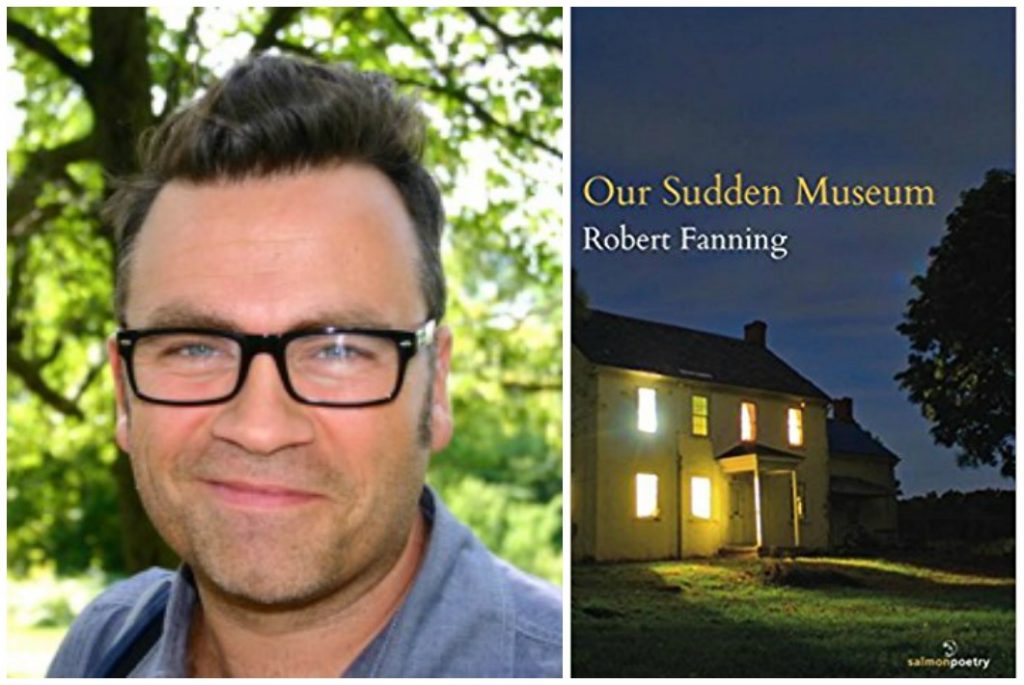

Robert Fanning’s previous full-length poetry collections include The Seed Thieves and American Prophet. A Professor of Creative Writing at Central Michigan University, he has also published two chapbooks, Old Bright Wheel and Sheet Music, and his poems have appeared in such journals as Poetry, Ploughshares, and Shenandoah. He lives in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan, and is featured online at The Michigan Poet.

I’m intrigued by the name of your new collection of fifty-nine poems, Our Sudden Museum. Would you share the significance of that title?

This title is culled from a poem that appears early in the collection entitled “Staying the Night,” in which the speaker visits the former home of his sister who died the day before. I found it to be a fitting title for this collection, which, among other things, investigates the sudden shock of loss—the book includes elegies for my sister, brother, and father. Among this book’s major themes and images is that of the house—that structure that is often what holds a family. What happens when that house is emptied of its inhabitants? When that house has grown vacant, or has become abandoned by the departure or passing of those who lived there? Our Sudden Museum considers who we are and what we leave behind.

Your opening poem, “House of Childhood,” and last poem, “Returning to the Fields I See We are No Longer There,” include the concept of returning. What is the importance?

Your opening poem, “House of Childhood,” and last poem, “Returning to the Fields I See We are No Longer There,” include the concept of returning. What is the importance?

In “House of Childhood,” one of a few sonnets that are something of support beams in the house that is this book—the speaker imagines/dreams he returns to his boyhood home and wonders even if he has become the very ghost or trapped bird that once frightened him as a child. In “Returning to the Fields I See We are No Longer There,” the speaker visits a landscape inhabited only by memory now. These poems, as do others in the collection, celebrate memory as a vehicle by which we return, in which we are given passage to our past, to our childhood—to our innocence. These poems also make us realize that the threshold to the past lives within our lives lead only now to open spaces—to emptiness—which we must confront.

How do you select the form your poetry will take such as in “Of Bricks and Vertebrae” and “House of Blossoms”?

Only when I am in the midst of a poem—sometimes several drafts in—do I begin to gain a sense of form as an organizing principle for whatever content has begun to arise. “Of Bricks and Vertebrae” is a great example. In this poem, a middle-aged speaker suffers the anxiety of worrying about the strength of his house, his body, his marriage, his family, his mind. The poem itself—what we call a concrete poem—is riven by fractures, by cracks—much like the fractures he is needlessly obsessing about in his domestic life. The poem itself, therefore, is nervous on the page. Form, for me, enhances and emphasizes content.

“Honeymoon Row” is a triolet. Why did you write it this way rather than free verse? Are there other kinds of formal poetry in Our Sudden Museum?

“Honeymoon Row” functions well as a triolet because the form itself—only eight-lines long and highly repetitive and rhyming, which works for a poem that is a bit obsessive and intense, a short, frantic burst—much like the marital argument that is the subject of the poem. In this collection, in addition to several free verse poems, formal poems include: sonnets, triolets, rhymed stanzas, prose poems, contrapuntals. Many of the free verse poems are held tight as well by internal rhyme—others use white space to emphasize rhythmic and conceptual gaps in the content.

What poets are your favorites, have influenced your style?

What poets are your favorites, have influenced your style?

Along with dozens of contemporary poets, I am also deeply inspired and influenced by the work of Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath, John Keats, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Theodore Roethke, and a few others. These poets are large close planets I orbit around.

Few major poets are equally skilled at writing and recitation. How were you invited to record at the Library of Congress and what did you select?

I was recommended for an interview and reading at the Library of Congress by a poet who heard me read at his college. To me, reading poems out loud—and doing so passionately and seriously—is an integral element of my work. Poems, as I often say, are like sheet music or a good campfire—they sing and glow when we breathe our notes into them. For that reading, I read several poems that are included in my most recent collection, Our Sudden Museum.

Besides working with college students, what other groups have you assisted in appreciating poetry?

Prior to being a professor, for eight years I was a Writer-in-Residence and Managing Director for InsideOut Literary Arts Project, an organization that sends poets and writers into the Detroit Public Schools. There I taught poetry to elementary, middle, and high school students. It was an absolute thrill and taught me a lot. I have also worked outside of the academy, occasionally teaching community workshops for children and adults. This is important to me, because poetry is not only a solitary endeavor, and it is not for the academy alone—we must give back what we’ve learned to our communities, and to others, who may not have had the chance to study the art.

Do you have an idea, a theme, about your next collection? How has your topics, way of writing changed?

I spend on average anywhere from five to ten years, sometimes more, on each manuscript. My writing style changes from book to book, often consciously and sometimes drastically, as I challenge myself away from defining my formal and structural boundaries. My most recent completed manuscript, Severance, features a far more organic, sound-driven texture—the poems, though linked in a book-length narrative, are individually less controlled and cohesive, more dream-like and driven by sound than sense. The narrative is a journey sequence, in which one marionette cuts another down and they escape the stage.

The body of work I am now completing is called A Man Carrying A Corpse. This manuscript, much like my second book, American Prophet, features narrative poems, in this case about a man who carries a corpse everywhere he goes. This, like Severance, is largely mythological, magical, metaphorical—a dream that may help us learn more about our waking life. I call the last several years of my writing life something of a fugue, as I’ve strayed willingly from realism. Beyond these two manuscripts, I’m now embarking on a third, tentatively untitled, that will veer back toward more formal, personal narratives—and probably into some very uncomfortable territory. Though I’m always pushing myself, there is a definite pendulum to my style, I veer outward, then return inward. I tighten into narrative and form, then venture outside the lines, then return. I hope one day in the future when looking back at my work, it looks a lot more like a beautifully meandering, dizzily winding river than a straight highway.

Hear Robert’s reading at the Library of Congress on the public radio show “The Poet and the Poem.”

Smallwood lives in Michigan: her recent poetry collections include, In Hubble’s Shadow (Shanti Arts, 2017); In the Measuring (Finishing Line Press, 2017).