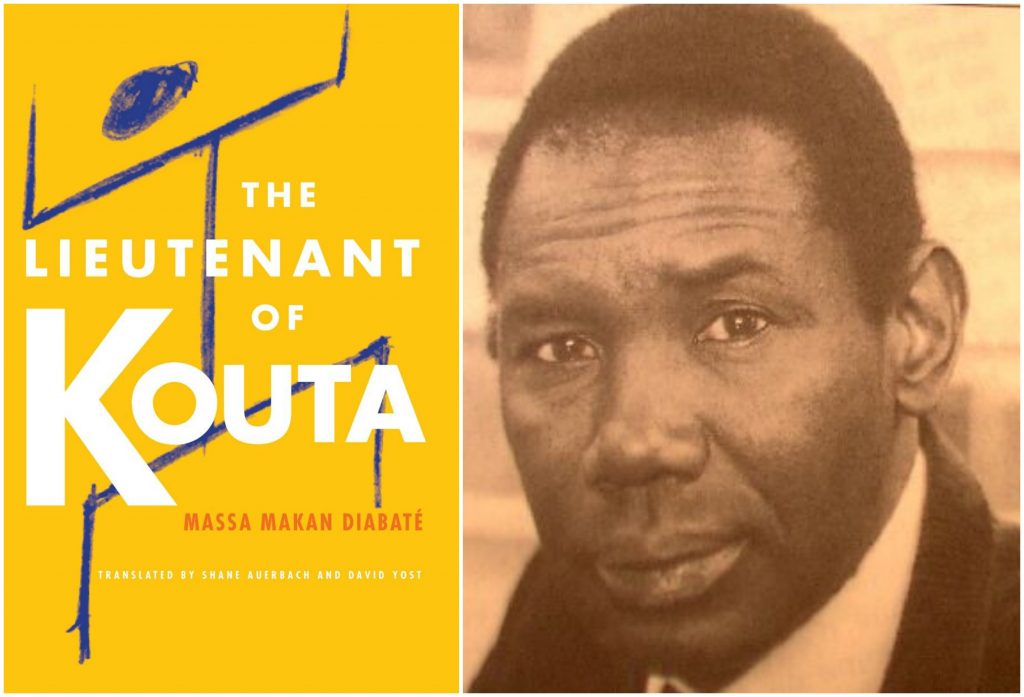

Chapter 1 of Massa Makan Diabaté’s novel, Le Lieutenant de Kouta (The Lieutenant of Kouta), appeared in the Fall 2001 issue of MQR. Translated from the French by David Yost and Shane Auerbach.

Chapter 1 of Massa Makan Diabaté’s novel, Le Lieutenant de Kouta (The Lieutenant of Kouta), appeared in the Fall 2001 issue of MQR. Translated from the French by David Yost and Shane Auerbach.

Hands bound, head covered in egg yolk, pulled by the lieutenant Siriman Keita, Famakan had no idea what he had coming.

“The whites!” the lieutenant screamed. “This is all the whites’ fault!

“In the old days, a child of seven years was already in the fields. Today, they want to educate them. And what an education! Monday, they sleep off the exhaustions of Sunday. Tuesday, they work a little. Wednesday, they get ready to go out on Thursday. And Friday, they start dreaming of Sunday. And the second they know how to write their names, they speak of independence.

“Independence? In other words, no more pension for the lieutenant. No more pension for all those who showed, on the other side of the sea, the courage of our race. It’s nothing but jealousy! Selfishness!

“Well, until the day they put dirt in my ears, the jealous and envious will find me here in Kouta, as sure as the sun follows the rain.”

The lieutenant drew out the whole village with his shouting. “It would have been better, Famakan, if an eagle had taken you from your mother’s back at two months old. Your punishment will be exemplary. It would have been better if your mother’s pagne had come undone in the middle of the market. Everybody could have seen her boutou-ba at their leisure! Her bushy slit. Nobody would have married her, and you would never have been born.”

The lieutenant drew out the whole village with his shouting. “It would have been better, Famakan, if an eagle had taken you from your mother’s back at two months old. Your punishment will be exemplary. It would have been better if your mother’s pagne had come undone in the middle of the market. Everybody could have seen her boutou-ba at their leisure! Her bushy slit. Nobody would have married her, and you would never have been born.”

The women covered their ears to avoid hearing any more, saying, “Some neighbor the lieutenant is! Such insults, and on such a beautiful morning! . . . And from the mouth of a man!”

“Famakan, your parents conceived you by day. We’re told over and over again not to do that during the day. The siesta has spoiled this country. The child of the siesta will never amount to anything! Such children have no right to life. In the old days, they were abandoned in a cave where they died of starvation; or the family matriarch, on the advice of the elders, performed a bleeding, and their blood drained softly, slowly, and for a long time, chasing off the evil that they bore.

“Go to a house in Kouta after lunch and ask for the father of the family. You’ll be told he’s taking a siesta. An improved siesta . . . Siestas make us ugly and unlucky. And the whites have their share of the responsibility. They put thieves in prison where they’re fed. In the old days of this country, before the whites’ arrival — with their laws, their judgments, their mitigating circumstances — well, thieves had long nails pushed into their heads, softly, slowly, and for a long time. They were buried alive. They had their throats slit in the town square with badly sharpened knives, to make examples of them.”

Famakan followed the lieutenant without saying a word, his eyes wild. He suddenly remembered what had happened to his classmate, Fakourou. It was the dry season; the harmattan was blowing, and the whole village had disappeared in the swirling wind. Fakourou had found a long cigarette butt at the edge of the market. On the Dotori Bridge, he saw a man smoking, snug in the old coat of an ex-soldier. Since many locals wore similar clothes, given to them by relatives who had gone to war in the white man’s land, he didn’t recognize the recently arrived Lieutenant Siriman Keita.

Fakourou asked the man for a light, his right temple bent forward, the cigarette butt pasted to his lips, awaiting the first, nostril-warming puff. The lieutenant had discreetly passed his cigarette from his right hand to his left. And by way of response, he gave Fakourou a slap so violent that the boy saw lights crisscrossing before his eyes! Scared out of his wits, he set off running from the Dotori Bridge to the school. He was seized by a high fever, and rumor had it that an evil spirit had beaten him.

Fakourou asked the man for a light, his right temple bent forward, the cigarette butt pasted to his lips, awaiting the first, nostril-warming puff. The lieutenant had discreetly passed his cigarette from his right hand to his left. And by way of response, he gave Fakourou a slap so violent that the boy saw lights crisscrossing before his eyes! Scared out of his wits, he set off running from the Dotori Bridge to the school. He was seized by a high fever, and rumor had it that an evil spirit had beaten him.

“This village needs to be ruled with an iron fist,” the lieutenant shouted, “like the Colonial Army! Until the day you die, you will never steal again. I, Lieutenant Siriman Keita, swear it myself. At the mere glimpse of a fallen object on the ground, you will flee in panic. Ah, the whites. There’s only one thing to teach the children of siestas: he who steals an egg today will steal an ox tomorrow.”

The people of the neighborhood who were eating their breakfast stopped passing bowls from father to son, from mother to daughter. All eyes followed Famakan, held by the lieutenant’s leash like a dog. Egg yolk ran into his eyes. He tried to wipe his face, but at that moment, the lieutenant pulled the cord taut, and Famakan collapsed into a mud puddle.

“Get up or I’ll slit your throat!” the lieutenant roared, drawing the saber he always carried on his belt.

“Kill me now,” Famakan murmured, “and let’s be done with it.”

“Not before I judge you!” threatened the lieutenant, catching Famakan’s gaze with the gleam of his saber.

They arrived at the square house, and Siriman immediately barricaded his door to keep out the crowd of onlookers who had followed him since the Dotori Bridge. Then he dragged Famakan into his living room, ordered him to sit on the floor, and bound his arm to a chair.

“Now, Famakan, let’s be frank. This egg — was it you who laid it, or one of my guinea fowls?”

“Has anyone ever seen a man lay an egg?”

“Well, you’re going to lay one today, and I bet it’ll be big enough to hang over the mosque.”

“Sir . . . ”

“Call me ‘Lieutenant’!” shouted Siriman. “It’s my rank; I won it under fire against the enemies of France while your father and your mother were frolicking like geckos in full daylight. I myself made some female conquests overseas. After all, I am a man; I eat salt, and he who eats salt . . . ”

He stopped and took on a menacing look. “And if, one day, a boy or a girl, child of some red-butted monkey, decides to come here, to Kouta, in search of his father, I’ll drag him behind the village by the tree nursery, and I’ll put him down with a revolver.”

“Lieutenant, I took an egg from beneath a bush, it’s true . . . ”

“So you admit the facts. Here is my sentence, then.”

“Whether it was a guinea fowl egg or a chicken egg, I’m not sure. And there’s no longer any proof. You broke it on my head.”

“Only guinea fowls lay their eggs under the bushes, and all of the guinea fowls in the village belong to me.” The response embarrassed him, and he added: “And even if it was a chicken egg, in my eyes, you’re still a thief. Your punishment will be severe, Famakan!”

He got up, looked around for a while, and finally went into his bedroom, returning with a revolver. He took a new rope from the wall and put it in a bucket of water. And to prolong Famakan’s torture, the lieutenant sat down in front of him, thoughtful, his head in his hands.

“Choose between the revolver and the rope,” the lieutenant finally said. “You want the revolver? Then I’ll burn your face, and until the day of your death, you’ll remember not to steal. The rope take your fancy? An old custom of ours! I’ll beat you until it crumbles.”

Famakan’s anxious gaze went from the revolver to the rope, and from the rope to the lieutenant’s face.

“Take your time, Famakan; I’m in no hurry. A retired soldier awaits nothing but death.” He picked up the revolver. “This weapon dates back to the First World War. It’s already served at Verdun. We should give it a test.”

An explosion of gunpowder made the walls tremble, and Famakan understood that the lieutenant, who was reloading his weapon, was not joking.

“Papa Lieutenant,” he said, sweetly.

“Don’t call me ‘Papa,’ of all things. I have neither wife nor child. And heaven grant that I never father a son like you.”

“Then I’ll be honest: I don’t want the revolver or the rope.”

The lieutenant jumped as if he’d been stung by a wasp. “Famakan, you have a sore asshole; you need to just take a crap and get it over with. I’ll go get you a third and final proposition . . . ”

“A thief, Lieutenant, should die in the mud. Everyone should see him struggle for his life before expiring.”

“So be it! I’m going to throw you from a bridge.”

“The Dotori Bridge, Lieutenant. It’s the highest in the village.”

“Agreed, Famakan!”

Followed by the gawkers waiting outside his gate, the lieutenant set out, holding Famakan by the rope.

“He’s suicidal,” the lieutenant shouted. “He chose that I throw him from a bridge. Let none accuse me of murder!”

Famakan knew the Dotori Bridge well. The children of the village came to splash about there during the rainy season, in the stagnant water, among the dead leaves and lilies. He knew the spot where a rock had injured him, and that farther out, there was nothing but mud and sand.

Now the lieutenant began to show some concern. “This would be too severe a punishment,” he said. “Let’s go back to the house.”

But already the young boy had grabbed hold of the lieutenant at the very edge of the bridge.

“I want to go, but not all alone.”

“Let me go, Famakan!”

They grappled like wrestlers, and the lieutenant, pulled over by Famakan, fell headfirst into the mud, legs in the air. To disguise his ruse, the boy dove in after him, to the applause, shouts, and laughter of the audience.

“Mark my words,” the lieutenant howled. “Whoever tells this story will have to pay twenty francs! Ten francs will go to me, and ten will go to Famakan.”

The lieutenant climbed out of the mud and cleared a path through the crowd, cursing: “The whites! . . . the whites, and nothing but the whites! They spoiled this country. It needs to be ruled with an iron fist, like the Colonial Army.”

Le lieutenant de Kouta. Coll. Monde Noir Poche; Editions Hatier, 1979—Editions Hatier International, Paris 2002. Thanks to Editions Hachette Live International.